(Photo Credit: istockphoto)

(Photo Credit: istockphoto)

*This piece originally appeared on LinkedIn.

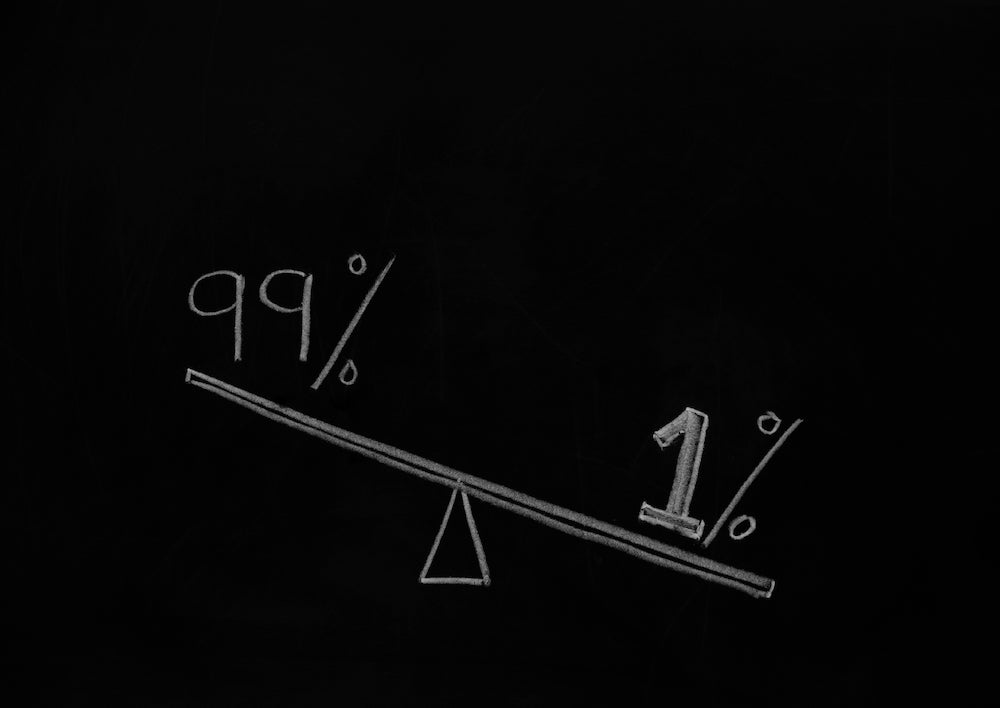

According to a new report from the Pew Research Center, the American middle class no longer represents the majority of the US population. “Middle-income” — defined today as having $42,000 to $126,000 for a household of three — now applies to about 50 percent of US residents, down from 61 percent in 1971.

The numbers demonstrate what we already know to be true. The massively wealthy are capturing more of the wealth of our nation and the number of poor are growing as well. The Middle Class is shrinking. With it, we are experiencing changes in spending power, economic opportunity, and in the culture of many communities — and our country is changing along with it.

Greater numbers of leaders in public and private spheres are naming growing inequality as a significant concern for the health of our nation.

Darren Walker, president of the Ford Foundation, appeared on Bloomberg Business recently to talk about plans for the organization he leads. The grant-making of this $10+ billion endowment will focus on inequality, here and overseas. Why appear on Bloomberg to spread the message? Because his message is: Inequality is bad for business.

Peter Orszag, former head of the Office of Management and Budget, now at Citigroup, weighed in: extreme inequality is bad for growth. Peter Georgescu, chairman emeritus of Young & Rubicam, penned a piece for the New York Times Sunday Review this summer that appeared under the headline, “Capitalists, Arise! We Need to Deal with Income Inequality.” He goes further than Orszag, saying if we continue down this path, we can expect social unrest or account-settling tax rates.

The Ford Foundation’s analysis of the problem features five forces driving inequality — as seen in their diagram below.

These forces — the rules of the economy, the cultural “narratives” we teach and tell ourselves about what is important, unequal access to government decision-making, and public goods — each of these could be the organizing principle for driving change. Each is complex on its own, but the links to business are revealed throughout. Now what?

Some of the “what-now?” is beginning to be aired in business school classrooms. With the Ford Foundation’s support, we issued a “Call for Teaching” in MBA classrooms about business practices that contribute to a more inclusive economy. This call states the obvious: business is a principal actor in building and expanding the middle class; it has to be at the table now with new commitments and more inclusive business models and reward systems.

It is hard to imagine business reverting to a US 1950s-style social contract, given today’s global and hyper-competitive markets, and technology and process improvements that allow for fewer employees. So how can firms and business leaders contribute to shared prosperity and long-term growth?

Our Faculty Pioneer Awards recognize teachers who prompt students to think expansively about their role as managers — not only about how they drive corporate performance, but also how they influence the way the economy works. Business scholars willing to take up the teaching challenge have the opportunity to ask fresh and timely questions:

- What metrics, economic models, and valuation tools actually support growth-creating investments?

- What can we learn from history and from other parts of the world about linking the performance of the business back to the incentives and compensation practices for executives and workers?

- What is the effect of global location decisions? What role do public-private partnerships, ownership structures, and the power and voice of business leaders play in setting policy?

Business decisions are cast in a new light when connected with the imperative to build a more inclusive economy.

Business faculty at Harvard University, the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University, and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) — and even the American University in Beirut — responded creatively to this call. Professor Shawn Cole at Harvard is teaching about financial services that could serve the world’s poor. At Kellogg, Professor David Besanko is teaching about “public economics,” flipping the b-school classroom on its ear by organizing his class around the public good, instead of profit maximization. Professor Thomas Kochan at MIT shows that managers — constrained by technology, markets, and their relative power over workers — can still decide to compete on the basis of “high road jobs.”

There are lessons from these classroom innovations. Business schools have the capacity to shape the minds and attitudes of future business leaders; faculty don’t change their curricula at whim. A problem as complex as inequality can’t be isolated in a module or elective — it needs to be woven into the core teachings about what is measured and rewarded to build a business that lasts. And to avoid treating inequality as the flavor-of-the-week, teaching must combine theory and practice.

Faculty willing to innovate in a space as complicated as this one need support and encouragement — from deans, from students, and from business itself. Programs like the annual Faculty Pioneer Awards offer up examples of what is possible, and are one way to model change.

Inviting change agents from the business world into the classroom is another. Western Union and MasterCard honored the work of these pioneering faculty by telling their unique stories at the awards ceremony; you can see the video here (at minute 6:50). These companies are addressing inequality by opening up new markets. They see opportunity where others see only cost.

Inequality is a grand challenge of the 21st century. Business innovators like these reinforce an important message: business is able to shift entrenched cultural narratives and influence the rules that govern the economy. Both business executives and educators have a critical role to play. Who’s next?

Judith Samuelson is the founder and executive director of the Aspen Institute Business and Society Program (BSP).