Two days into the New Year, Anthony Banbury, former head of the UN Mission for Ebola Emergency Response, envisioned an end to the Ebola crisis. “Going forward,” he said, “it’s going to be extremely hard for us to bring it down to zero [cases], but that is what we will do. I believe we will end Ebola in 2015.” An end to the Ebola crisis, however, will not necessarily end the development crisis it triggered, or curtail the misperceptions of investment risk it perpetuated.

Economic resiliency, recovery of the past decade’s gains and continued GDP growth for the “epicenter” countries of Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia are by no means guaranteed as we near a prospective end. But at some point, whether in 2015 or the coming years, the countries will have the opportunity to reestablish their economic growth drivers. Tourism will rebound, agricultural production will flourish and the mining industry will once again cut smoking swaths of land from the countryside. Commercial industry, in one form or another, will return. Less certain to make a comeback, or at least a quick one, is the nascent financial infrastructure which had begun linking the countries’ rapid GDP growth to opportunities for those at the bottom of the pyramid. It is in rebuilding and expanding this infrastructure that the philanthropic community will have a key role in the coming years.

Since 2001, per capita income had risen in all three countries at the nexus of the epidemic. Governing bodies once embroiled in civil discord had begun to refocus their energies on economic development, and, by several macroeconomic indicators, they were succeeding. But economic growth, no matter how hard won, means little if untethered from the populace or systemically unavailable to the disenfranchised. Across West Africa, socially driven financial entities such as microfinance and development finance institutions have gradually helped to address this disconnect, providing an invaluable link between an improving economic environment and those traditionally last to realize its benefits. In the midst of the Ebola epidemic, however, the future of these entities remains uncertain.

There are, of course, many areas in which the epicenter countries must start over, profound infrastructure and equity gaps in which they must begin anew, but there also areas which philanthropy can help rebuild. In reestablishing labor activity, for example, we should not forget that a microfinance market has emerged in all three countries, or that, for many entrepreneurs, the crisis marked the first time they had ever missed repayment on a loan.

Great economic gains have been made in the past decade, and they can be made again. It will be philanthropy’s role to help build up the infrastructure of an inclusive economy – one in which post-Ebola growth is far more equitable, diversified and resilient to the shocks of future crises for the vulnerable.

“The Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreak in the Mano River Union countries of Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia is one of the most complex developmental challenges in recent times.” — United Nations Development Program

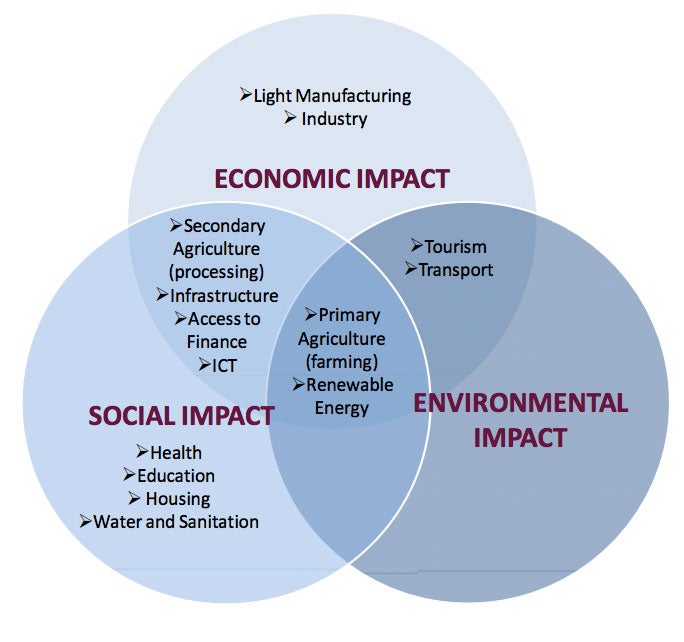

Between 2000 and 2013, the annual growth in the epicenter countries averaged 2.79 percent in Guinea, 8.21 percent in Sierra Leone and 10.18 percent in Liberia. Just over a year ago, The Economist magazine’s Top Growers report projected Sierra Leone would have the fourth fastest growing economy in 2014, and Liberia was among the quarter of African countries that grew at seven percent or higher in recent years. Moreover, the three countries had gradually begun to diversify the sectors contributing to their growth, developing industries such as agro-processing, tourism, light manufacturing and financial services.

The epidemic has destabilized all of these sectors, as well as the “high impact” systems that employ or support the country’s most vulnerable populations. The educational system has collapsed, for example, with nearly five million students out of school, and stagnant agricultural production and trade restrictions risk triggering near-term food crises. In response to these trends, and in keeping with several recent growth revisions, the World Bank adjusted their 2015 forecast in late December: 2015 growth estimates are 3.0 percent in Liberia, down from a pre-Ebola 6.8 percent; -2.0 percent in Sierra Leone, down from 8.9 percent; and -0.2 percent in Guinea, down from 4.3 percent.

At the macro level, redevelopment will begin with fiscal rebalancing as revenues and expenditures continue to diverge (particularly in the health sector), labor market production remains depressed and epicenter countries face the inflationary risks of border closings. At the micro level, recovery means providing families and communities with sustainable pathways to economic security. Over the past year, farmers have missed their harvests, artisans have seen their businesses deteriorate and, most detrimentally, families have lost their breadwinners. In terms of morbidity and mortality, for example, the virus disproportionally affected the most economically active populations in these countries — people in the 15-49 age groups. Compounding direct economic costs, the epidemic removed from many communities those most likely to have led redevelopment in its aftermath.

Individuals who attempt to resume labor activity still face market closures and movement restrictions along with an unpredictable and drastically-reduced consumer base now with diminished purchasing power. Resumption of economic productivity by these individuals and re-empowerment of the labor force will depend, among other aspects, on levels of access to capital. In the agricultural sector, for example, farmers will need capital for the purchase of agricultural inputs such as irrigation equipment and seeds.

Who will provide the funding to purchase these items, or the patient, flexible and creatively-structured investments to help farmers do so themselves?

Mobilizing capital for this purpose will not be easy given the weakened state of the infrastructure and enterprises which normally lead in these efforts. According to a recent United Nations Development Program report, “microfinance, which is the main source of funding for many micro and small businesses, is being wiped out due to non-payment of loans and the death of many participants.” The Center for Financial Inclusion reports that the region’s now-weakened microfinance market included 53,000 borrowers in Liberia, 110,000 in Sierra Leone and 117,000 in Guinea. In Lofa County along Liberia’s northern border, for example, most women have not been able to repay their debts since June 2014. And in a September 2014 blog post, Kiva, a nonprofit microfinance organization, reported a freeze among several field partners in epicenter countries: “Kiva Field Partners BRAC Sierra Leone and BRAC Liberia have suspended microfinance operations for at least a month. SMT in Sierra Leone is stopping disbursements for at least a month. Field Partner ARD, in Sierra Leone, has also stopped loan disbursements in the worst affected districts and is considering suspending all operations in these areas.”

The global community must act quickly to secure both the assets of these entrepreneurs and the infrastructure which first supported them. As borrowers continue to default on loans, for example, we must ensure that a lack of payment in crisis does not deteriorate market access in recovery. Without both regional and international support, undercapitalization and revenue losses will drown socially-driven financial entities at the moment they are most needed — an ecosystem which includes not only microfinance institutions but private equity and venture capital funds, development finance institutions, foundations and institutional investors. All of these entities, particularly those operating exclusively in epicenter countries, have sustained losses in the past year. Few will have the balance sheets or assets to withstand them without assistance.

No single instrument, form of capital or partnership structure will be universally effective in supporting these entities. Rather, philanthropists should leverage their full development toolkit — an evolving capital set which includes instruments such as bank deposits and bridge loans in addition to traditional forms of grant funding.

In 2011, Rockefeller Foundation and Dalberg Global Development Advisors reported that annual impact investments and commitments in West Africa were greater than $3 billion, with demand estimated at $65 billion between 2010 and 2015. Investors, including private equity and venture capital funds such as ManoCap and the West Africa Venture Fund, as well as foundations such as Cordaid and the DOEN Foundation had begun to meet this demand in epicenter countries, stewarding socially-driven finance into economies which had lagged far behind neighbors such as Nigeria and Ghana in terms of formalized impact investing. The report provides a number of strategies to cultivate this nascent industry — an effort which has become even more essential as the virus continues to take not only lives but livelihoods in the affected regions. Among other recommendations, the report urged nations to:

Build networks and awareness: These networks would span not only impact investors, but also business support organizations, government actors, and development partners (including bilateral donors, non-governmental organizations and other grant-making organizations).

Link with the global network: Initiatives to build the impact investing industry are underway globally, but are yet to make their presence felt in West Africa.

Cultivate talented entrepreneurs: To receive impact investment, strong operational and financial management capacities are required. These capacities can be difficult to find in West African enterprises; therefore most investments involve working with the enterprise to develop required capacities, pre‐ and post‐investment.

The epidemic cannot be allowed to end the past decade of economic progress for these countries, but it can and should be an opportunity to pivot that progress to more effectively incorporate those at the bottom of the pyramid.

“What I fear most is the impact of panic, which will be interpreted by businesses and investors as if we don’t know what to do,” African Development Bank Group President Donald Kaberuka said recently. “That cannot be the new narrative of Africa.” As the epidemic subsides, the global philanthropic community can play a central role in shaping this post-Ebola narrative, going beyond indicators such as GDP to secure not only growth but resilience, not only wealth but value creation for the most vulnerable. The next decade’s investments, whether they originate in the philanthropic, government or private sectors, cannot allow half of the nations’ populations to live in continued poverty, nor can they leave countries such as Liberia, which still lacks a basic electrical grid, shrouded in darkness.

The philanthropic community must match its dynamism as the epidemic spread with long-term commitment as it recedes. They have the opportunity to reset the long-term vision for the epicenter countries, to foster growth that can withstand crisis and progress that includes those who have been systemically left behind.

In this endeavor, they are just beginning.