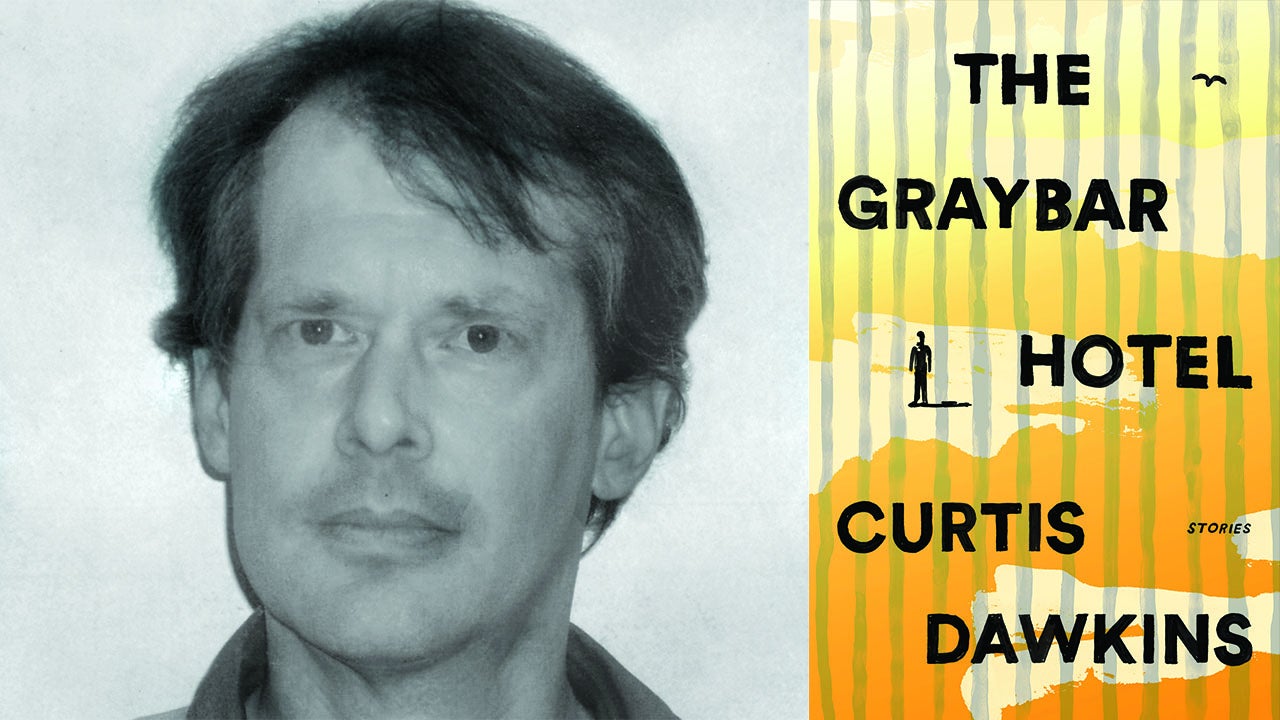

Photo by Lucas Flores Piran

Aspen Words will confer the inaugural $35,000 Aspen Words Literary Prize this year, recognizing a work of fiction with social impact. Twenty nominees still in the running, and the diverse list includes 12 novels and eight short story collections covering a variety of critical issues and published by an array of presses. While the jury works on narrowing this list down to five finalists and a winner, Aspen Words will bring you a series of Q & A’s with the nominees, who answered questions about their work, the importance of fiction in understanding contemporary issues and the books that have influenced them most.

Curtis Dawkins wrote his debut short story collection The Graybar Hotel while serving a life sentence without parole in a Michigan prison. Dawkins earned a Master of Fine Arts degree in writing before he committed his crime in 2004, following a struggle with alcohol and substance abuse. The stories in the collection offer a window into prison life through the eyes of his narrators and their cellmates.

Why did you write this book?

To save my life. People, especially English majors (I know, because I was one), like to talk about the power of words, but I honestly do not think I would be alive had I not had these stories to get my mind off the circumstances I had found myself in, i.e., prison, in 2005. I began writing the first story, “County,” the day I showed up to Quarantine (the six-to-eight week destination where new arrivals are tested and observed to see which prison and programs to send them to). That story’s first line kept repeating itself in my brain until I wrote it down. I was drawn back in by the siren song of fiction. Except these songs called me to their rocks because these rocks were stable and familiar.

What was the most challenging thing about writing this book?

Trying to find an audience for the stories. I thought they were decent and I wanted to share them, like letters in a bottle, to basically say I’m not dead. I still have worth. But then I had to re-learn this lesson: Publication is not the end-all and be-all of fiction, or any sort of art. Creation is the thing, but it seems I have to re-learn that pretty frequently. Eventually it all worked out, but I could get very few literary magazines (and none of the “big shots”) to publish any of them.

How might fiction help us explore contemporary issues?

I think the environment I’m in, prison, is falsely portrayed 90 percent of the time, sacrificed on the altar of entertainment, and the only way someone locked up can tell the truth about the good and bad of this place is fictionally. There is nothing more true than what’s found in beautifully made-up stories. Since they are “made up,” readers’ defenses are down. We prisoners are notoriously unsympathetic because of where we ended up, but for some reason if the inmates aren’t “real” there’s no need for those natural defenses. I think that the prison-industrial complex might be the lone issue only explorable (at least firsthand, by a prisoner) by fiction, though the “boundaries” point is applicable for issues dealing with race, addiction, sexual harassment. Every issue in today’s society is best explored through fiction. At least, I think so, though I have always been partial to that art form.

The men I am among are not a joke, and yet every day you can hear smart, funny, admirable people make jokes about prison rape. I have heard them told by everyone regardless of political affiliation. Prisoners are seen as animalistic jokes by nearly everyone. But we aren’t, and the power of writing is I can give a voice to these men who have never had one. These stories are the only way most people will ever get to know a prisoner. Some of us are not bad people, and all of us have something good inside them.

What was an early experience where you learned that language had power?

It was a poem that actually changed my life, but so much was/is contained in those couple of pages that the thing might as well be a novel. I was foundering in college, just drifting on a lake of whiskey and Budweiser. I took a British Poetry class because I had a half-assed idea of being a lawyer, and my undergrad advisor advised me that law schools like applicants with an eclectic academic record. I had a great teacher in British Poetry, and I remember the day we went through “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.” Incidentally, I have Eliot reading “Prufrock” on my player as I write this. I could relate to Prufrock’s feeling of alienation. That’s putting what I felt very simply, but that day in class literally changed things for me — not immediately — but a great seed was planted.

I dropped out of college within the year, but returned four or five years later with the intent, this time, of doing what Eliot did in that poem — making people feel. Literature does that better than any other art form because it affect us on the most personal of levels — our secret thought life, things we do not share with another living soul, except maybe our dog.

I’m reading A Visit From the Goon Squad presently, along with my partner and novelist, Kimberly Knutsen, in our own little book club. I’m reading that book because I had just finished Egan’s Manhattan Beach. Books by great writers like Jennifer Egan change my life totally, 300 pages at a time. Again, and this seems to be my refrain with these answers without fiction to remove my mind from prison, I don’t think I would have made it.

I am grateful every day for books, to write them and to read them. Fictional people are the ones I get along with best. That isn’t a sad statement, but a joyous one. I am never alone. Just give me some good (bad books have a bad effect on me) books, no matter the genre, and I’m completely content.