Aspen Words will confer the inaugural $35,000 Aspen Words Literary Prize this year, recognizing a work of fiction with social impact. Twenty nominees are still in the running, and the diverse list includes 12 novels and eight short story collections covering a variety of critical issues and published by an array of presses. While the jury works on narrowing this list down to five finalists and a winner, Aspen Words chatted with the nominees about their work, the importance of fiction in understanding contemporary issues, and the books that have influenced them most.

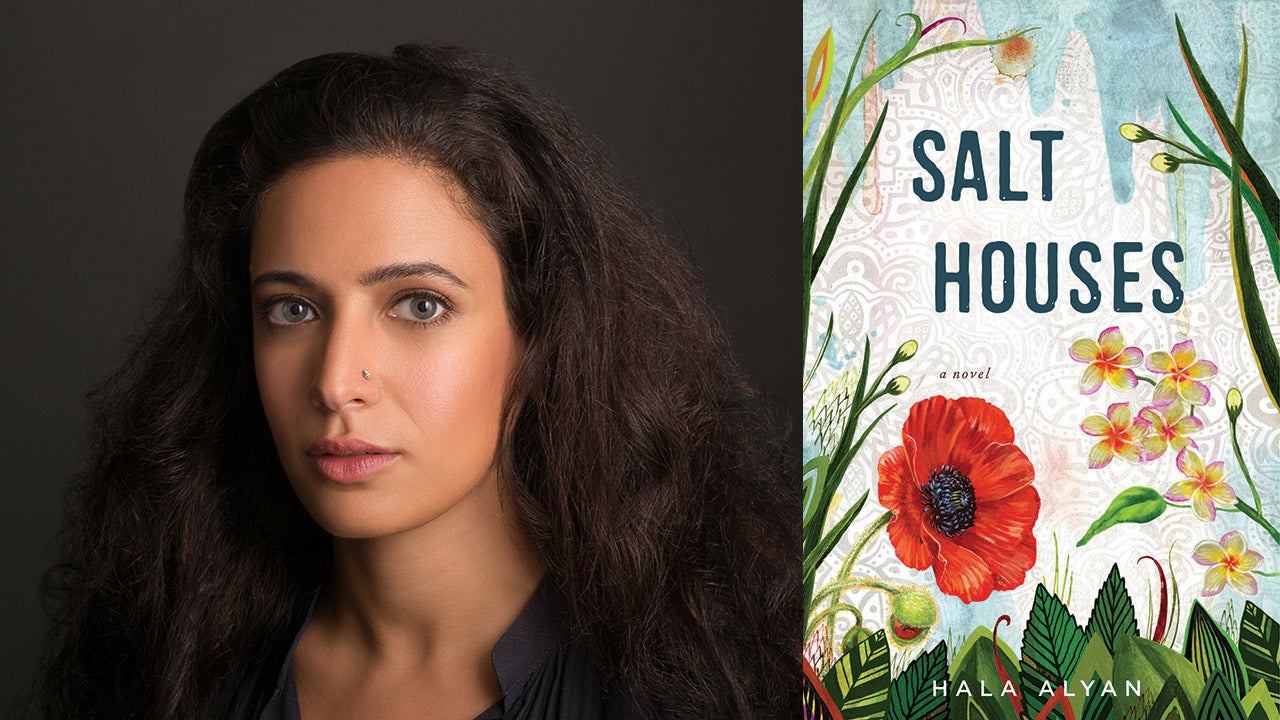

In her debut novel, Salt Houses, Hala Alyan tells a story of the displacement of a Palestinian family over the course of many generations. Alyan knows what it is like to feel like you belong nowhere. Her own family underwent the same trauma as they attempted to recreate a home for themselves in foreign lands. Through the perspectives of different family members, Salt Houses examines culture, history, and wounds that never fully heal.

Why did you write Salt Houses?

I grew up in a family of storytellers, and it was the combination of this tradition of storytelling and the larger historical context (of Palestinian immigrants) that led to my fascination with writing about diasporic memory and loss. For a long time, I had to pretend I wasn’t writing a novel, but rather just following my curiosity about this one family and where their immigration took them. I’ve always been intrigued by how we are all broken and remade by family and wanted to write something about that, against the backdrop of political turmoil. In many ways, I’ve been writing this book my entire life.

What was the most challenging thing about writing this book?

The truth is Salt Houses taught me a lot about how to write. I was challenged and pushed to become more patient, to let the story breathe, to accept that, sometimes, characters will be a little disobedient. The biggest technical difficulty was the editing process since I wrote in a chaotic, non-chronological fashion, so going back and stitching all the scenes into one coherent narrative was exhausting. Emotionally, I struggled with writing about Alzheimer’s, as I watched my beloved grandmother suffer from dementia.

How might fiction help us to explore contemporary issues?

Telling a story of emotional inheritance in the context of immigration, of how a single family can be torn apart and mended against the backdrop of political chaos. I felt an urgency to create a narrative where a Palestinian family wasn’t just Palestinian, if that makes sense, but rather transcended their circumstances. This felt crucial to me. When I wasn’t working on the novel, I’d sometimes imagine the characters in their frozen lives, waiting for me to finish. It was an intense but sustaining process.

What was an early experience where you learned that language had power?

I can vividly remember receiving praise from a teacher in elementary school for a little story I wrote about a girl with superpowers. I was a gawky, painfully shy kid who couldn’t bear to speak up in class, so to have her take me aside and tell me the story was beautiful — I still remember how she said it, emphatically, like she knew I would doubt her words—made me realize that I had the ability to impact others.

What book(s) have made you see the world differently? How?

Books like The Joy Luck Club by Amy Tan and The Namesake by Jhumpa Lahiri completely upended my worldview—in the best possible way. Here were characters who spoke different languages at home, who ate food that others found unpalatable, who had to find a home in the emotional borderland to belonging (and not belonging) to two cultures at once. These books helped me hold my head up high at a time when I would’ve given anything to be like everyone else.