Aspen Words will confer the inaugural $35,000 Aspen Words Literary Prize this year, recognizing a work of fiction with social impact. Twenty authors made the longlist which included 12 novels and eight short story collections covering a variety of critical issues and published by an array of presses. The five finalists were announced this week. Aspen Words chatted with several longlist nominees about their work, the importance of fiction in understanding contemporary issues, and the books that have influenced them most.

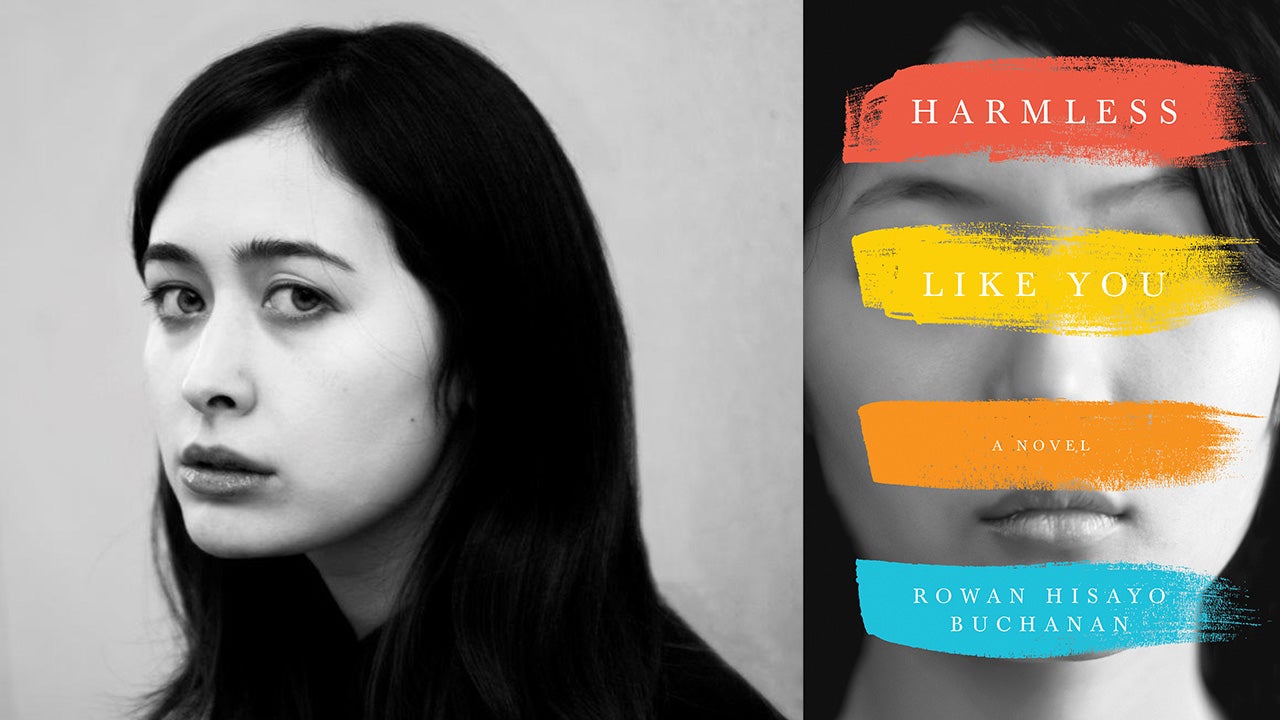

Rowan Hisayo Buchanan’s debut novel Harmless Like You centers on how children inherit identity. It follows Yuki Oyama, a young Japanese artist struggling to make it in America and her son Jay who, as an adult in the present day, must confront his mother’s abandonment. The novel was a New York Times Editor’s Choice and an NPR 2017 Great Read.

Why did you write Harmless Like You?

A book takes years to write and you need many reasons to keep going.

Harmless Like You began when my mother lost her memory. She forgot the year. She forgot what country she was in. She forgot who had given her the bagel she had in her hand. It was all gone.

We had no idea what was happening. I was in New York at the time—thousands of miles away. All I could do was sit in my chair and stare at the phone. I wanted to talk to my mother, but I didn’t even know if she’d recognize my voice. My father rushed her to the hospital. It emerged that she had something called Transient Global Amnesia. The condition is non-permanent. Her mind recovered.

In the months afterwards, I began to think about who I would be without my mother. There were many things she’d given up to care for me. There was another life she might’ve had. And so I began to write about a different woman—one who left. I started with a 16-year-old girl, standing on a street in New York being ignored by a flasher. She was 16 when my mother was 16. She lived in New York, as my mother did. But this girl would grow up, have a child, and leave him. I wanted to know why.

I kept writing, and as I did the reasons for the work changed. I wrote Harmless because I grew up hearing my mother’s stories about New York in the sixties and seventies. It’s a pop-culturally popular era. I knew so many girls with posters of Breakfast at Tiffany’s in their bedrooms. But in that movie Mickey Rooney performs in horrific yellow face. He was so unlike an Asian person that I didn’t even understand that he was supposed to be Japanese. My mother is half Japanese and half Chinese. Families like mine don’t appear in those movies. And so, I was excited to write a novel about a Japanese family living in that era.

Then there were times when I wrote only for the love of the words. A sentence can trick its way into your head and demand to be given a story. Books are almost always smarter than their authors. I wanted to try to put my best thoughts in one place and see what happened.

How might fiction help us to explore contemporary issues?

Philosophers are, in their own way, fiction writers. Plato’s Cave is a very short story. This is no coincidence. Stories stretch our thinking. Much of the more poisonous rhetoric today seems to come from an unwillingness to feel for others. This makes books, especially books about and by people whose stories are underrepresented, all the more important.

When we leap into a character’s life, we enter a thought experiment. We put ourselves in different life circumstances. We see why actions that at first seem inexplicable are taken. We invest our hopes in the hopes of someone unlike ourselves. And when that character makes mistakes, instead of judging them we can choose to see that bad choices might be the result of a human pushed beyond the person’s capacity to cope.

Certainly, plenty of unkind people have enjoyed novels. But for those who read with a desire to be more empathetic, fiction can provide the training wheels. Fiction opens our minds to problems and dreams very different from our own. And hopefully that can help us treat each other with greater kindness.

What was an early experience where you learned that language had power?

I’ve always been struck by the way babies become obsessed with the word no. For months and months, the only way to communicate their desire has been to weep. Suddenly, they have this word. And this word allows them to shape the world just a little. It allows them to make the world slightly closer to the way they want it to be.

I don’t remember my first no. I was too small. But I’ve always seen language as a way of shaping my world. I remember a time when I was about twelve years old and friendless. The reasons for this friendlessness were complex. But I found that I could escape the consuming loneliness by reading. I could swap out my life for the life of somebody in a book. I skipped class to read. Everywhere I went, I held a book. I reached my library limit and took to sneaking books in and out, tucked up inside my sweater. I read the way a hungry person wolfs down food—so fast she forgets to taste. I read widely: fantasy, detective, romance. But I loved best the books about others whose minds were a little like mine. A world in which these people existed seemed as magical as a world with dragons. And so these were the voices with which I filled my days. This too was a form of world-shaping.

What books have made you see the world differently?

All the best books shift your vision of the world at least slightly. But here are three that stand out in my memory:

Love in A Fallen City by Eileen Chang—This book about 1940s Shanghai helped me understand the world my grandmother left behind. She always told me she didn’t miss China because her China was gone. I knew she loved Eileen Chang and I was delighted to find out I did too.

Autofiction by Hitomi Kanehara—I read this book for the first time when I was fifteen. The protagonist is funny, mean, and a little off-kilter. I delighted in this book about a woman who wasn’t nice or sweet in any traditional way.

Changing My Mind by Zadie Smith—Smith’s fiction has always moved me. But these essays model a way of being. In them, she is both emotional and intellectually rigorous, a mode which women have traditionally been told is not possible. But it turns out you don’t have to choose.