“What is the future of work?” is a question state policymakers are exploring. The answer is complex, and cuts across a wide range of topics and issues—including technology, education, workforce, worker benefits and protections, and more—that are already quite complex when you consider them in the present. For example, 45 of the nation’s governors addressed concerns and priorities around the future of work and preparing the future workforce in their state of the state addresses earlier this year. Several states are participating in national projects to develop new strategies to prepare the future workforce and to better understand and support the on-demand workforce in their states. However, the challenges of addressing these issues are even greater given the uncertainty about the scope and rate of technological and economic change. Take the automotive industry for example: technology, automation and globalization have already brought dramatic change to auto manufacturing in the United States, changing jobs, companies, and communities. On top of these changes, the conversation today has shifted to how quickly automation and technology will allow for a truly autonomous vehicle. What will this mean for drivers, particularly those whose occupation is centered on driving? What skills will be required in a new ecosystem of autonomous vehicles, and where and how will people learn those skills? When might this change take place?

To prepare for the challenges around the changing nature of work, stakeholders from across each state—including policymakers, businesses, labor, educational institutions, and workers—need to develop a shared understanding of the challenges and opportunities, as well as develop policy and regulatory responses to prepare the workforce for the future. Some states are farther along in this process than others. After establishing the first Future of Work Commission, Indiana Governor Eric Holcomb has vested ongoing responsibility for this set of issues with the Governor’s Workforce Cabinet, a 20 member group that aims to assess and realign Indiana’s workforce development programs and services by promoting collaboration among employers and local partners. In Virginia, a cabinet-level advisor oversees a range of programs that connect Virginians to skills, training, and opportunities. Virginia’s Chief Workforce Development Advisor also works with leaders in labor and business to identify and fill vacant jobs in high demand sectors.

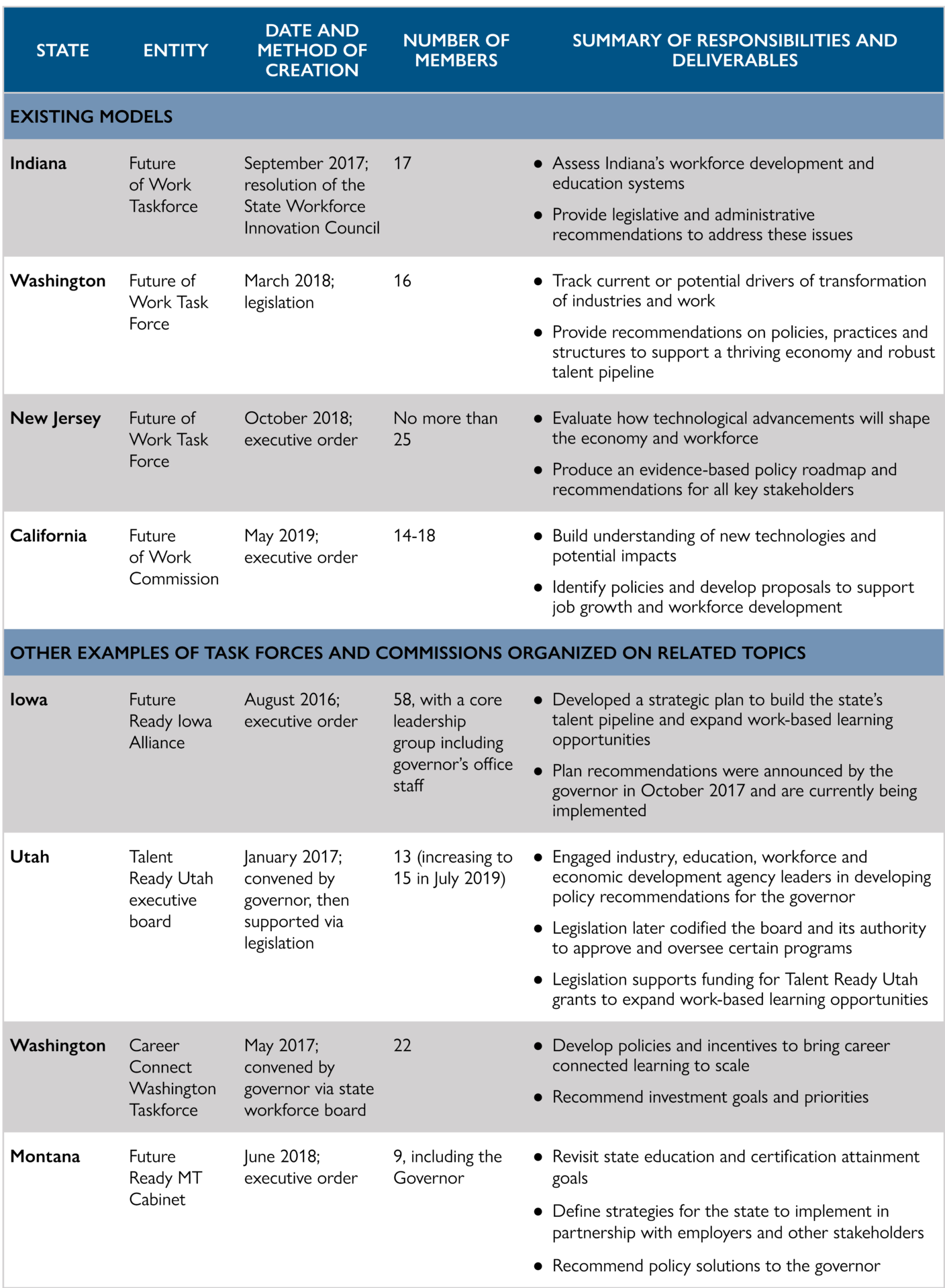

Like Indiana, other states have established or are in the process of establishing Future of Work Commissions or Task Forces, including Washington, New Jersey, and most recently, California. For these efforts to be successful, and for other states that are considering the creation of a commission or task force of their own, it is important to consider existing models—both contemporary and historical—and explore best practices.

There are several existing models of future of work task forces and commissions that have been implemented recently in various states. A summary of these efforts appears at the end of this piece.

Among recent relevant efforts, Indiana’s Future of Work Task Force was the first to form and the only one to complete its work to date. Created by Indiana’s State Workforce Innovation Council, which was housed in the state’s Department of Workforce Development, with strong support from the commissioner of higher education, the task force served a short-term information gathering role for a period of less than a year. The commission—made up of economists, business leaders, education and workforce training leaders, and worker advocates—gathered and presented information on key issues, such as demographics, strengths of various industries, education levels, and anticipated changes due to technology and other factors. The commission met four times, and those meetings engaged those with early interest from the state legislature, state agencies, education institutions, community partners and employer partners in charting a path forward. In order to act on the Task Force’s work, policymakers in Indiana took steps to establish a more permanent governance mechanism for future of work issues, housed in the Governor’s Workforce Cabinet.

Approaches & Best Practices

There are a variety of issues that those creating or facilitating a commission or task force might consider, including but not limited to:

Size and Composition

The combination, number and level of individuals appointed to serve can have an important impact on the success of the commission. First, it is essential to include a broad but strategic mix of stakeholders. For the issues likely to be considered, key groups include: educators; employers, especially from industries with a significant presence in the state and those industries most likely to be impacted by automation and technology, and representing both small and large employers; worker advocates; and policymakers. Geographic diversity, including members of urban and rural communities, is important given the different challenges facing these areas. Second, the size of the group should be large enough to ensure representation of key stakeholder groups, but small enough to promote productive conversation. Based on existing models, a range between 15-25 individuals appears likely to strike that balance. For larger commissions, policymakers might consider smaller, issue-specific working groups. Third, those appointed should be decision-makers empowered to represent and mobilize their organizations, but not so senior as to prevent active and engaged participation. In any case, conveners should build processes and norms to ensure that the group trusts one another. Ideally, a Future of Work Commission will enable frank conversation, including respectful disagreement, but will establish a process to resolve differences and move forward constructively.

Leadership

Successful state commission or task force efforts benefit from clear support from a governor and other public and private sector leaders. Governors have uniquely strong convening authority and can bring together cabinet officials, educators, key industry representatives, and prominent state legislators to discuss economic and workforce development priorities for their state. Effective gubernatorial support for other types of commissions and task forces has come in several forms, including executive orders to organize the group and its goals; convenings hosted by the governor’s office to bring together members and other stakeholders who will be impacted by the group’s work; prominent inclusion in state of the state addresses; and financial support included in governors’ budget proposals. Generally, the task forces or commissions whose work has had an impact on state policy benefited from their governor’s leadership in defining their goals and deliverables, including specific policy recommendations to the governor, that are in line with the state’s broader strategic objectives.

In cases in which task forces or commissions are set up by a state’s legislature, it is similarly important that the group has a clear set of goals and expectations defined at the outset of its work, and that it is clear how the products of that group’s work will be used by the state. Legislative bodies can provide this type of guidance and leadership in forming task forces or commissions.

Scope

The “future of work” is an umbrella term that has come to include a range of issues and questions. As a result, a commission on this topic could have a broad mandate or could take a more specific focus. In addition, defining the time horizon/s to be explored is essential. Examples of questions a commission might examine or address include:

- What industries and/or occupations are likely to change in size or nature over the next decade (or other time horizon, as specified by the commission or task force) due to demographic or other non-technological factors?

- What types of technology or automation have been demonstrated that might impact the economy and labor market in the future? On what time horizon might we expect various technologies to augment or displace human workers?

- What kinds of skills training will be required for the jobs of the future? What models for education and training make sense for the future of work?

- How might employers and others providing skills training stay connected in real time to ensure that training offered meets employers’ actual workforce needs?

- What funding mechanisms can support lifelong learning? To what extent are different approaches required for workers displaced late in their career?

- How do work structures and arrangements—those in place today and those anticipated in the future—impact the social contract? In what ways does this shared set of responsibilities—between employers, workers and society—need to be updated to map to the ways people are earning income today?

There are trade-offs between defining a narrow focus and tackling a broader set of issues. A broad scope would enable commission members to explore and appreciate the interconnectedness of the variety of issues at hand, but may not enable great depth of inquiry or specificity of recommendations. However, a narrower scope could support a greater degree of relevant expertise among commission members, and could enable more thorough consideration of alternatives and more specific recommendations.

Collaboration across state agencies or departments

Any of the questions referenced above are likely to cover issues currently managed by a variety of departments or agencies within a state government. To ensure that the work of a commission or task force leads to meaningful conclusions, it should be directed to collaborate with relevant agencies or departments. For example, collaboration between the agencies responsible for labor and employment, education, and economic development is essential. Beyond that, other areas of crossover may include: economic development, finance, and administrators of any relevant safety net programs.

Defining Responsibilities and Sequencing the Work Process

Those creating or facilitating future of work commissions or task forces should establish the work required by the group, including defining any reports, recommendations or other deliverables. Lessons for future of work task forces on how to structure and define responsibilities can be drawn from previous task forces or commissions focused on other work or workforce-related topics that have been successful in impacting policy change. Based on some of these existing models, responsibilities for an effective task force or commission may include:

- Establishing a shared understanding of the issues and challenges: A commission may use existing data or collect new data to create an evidence base for the conversation. This step is critical to creating a shared definition of the challenge, designing solutions and ensuring that findings are evidence-based. Commissions or task forces on this topic may wish to use the tools of scenario planning to explore a variety of assumptions about change in technological adoption, labor market conditions or the economy. This stage may be substantial enough to justify a stand-alone report of findings.

- Idea generation and assessment: A commission may look at policy/regulatory, private sector/employer, education/training and worker advocacy approaches implemented elsewhere, or may consider novel approaches. This phase may be most valuable if it encourages and surfaces the widest possible range of ideas.

- Delivering recommendations for action: A commission may be tasked to deliver a set of recommendations. These may be limited to those in service of a particular articulated objective, or those that can be accomplished through policy or regulatory change, or they may be broader. If a commission will be tasked with delivering recommendations, it may be worth reviewing the experience of commissions on other topics that were successful in identifying solutions and prompting action. Those recommendations may include specific policies, types of partnerships or areas for collaboration between sectors or stakeholders, and concepts for go-forward governance of these issues by elected and appointed leaders. Requiring a commission to produce concrete suggestions also gives members an action orientation and protects the effort from being used as a way to delay policy action.

- Producing a final report: The commission may be called upon to publish a final report of its findings. This could include findings from a data/evidence-gathering phase, a catalog of interventions considered and recommendations for how to proceed. A final report, however, may signal that work on the issues at hand is complete, when in fact it may just be beginning; relatedly, it may challenge the commission to resolve matters for the purpose of the report rather than allow them a more natural timeline for adequate consideration. One way to address these concerns is to call for a “report on progress” as opposed to a final report, as does the California Executive Order.

Taking the Career Connect Washington Task Force as an example of approaches to structuring and defining responsibilities, this group began their work by gathering data on labor market needs and on career connected learning programs and participation across the state. They also established shared definitions of key terms and concepts to then be used consistently across workforce development, education, and employer stakeholders, and used these definitions and sets of data to inform their policy idea generation, assessment, and recommendations to the governor in early 2018. Since the governor had been involved in the launch of the Task Force and engaged in the work on an ongoing basis, the recommendations were welcome and influential. Since delivering these recommendations, the Task Force was dissolved and a more permanent entity put into place to carry these recommendations forward and to coordinate career connected learning initiatives across workforce development, education, and employer partners. Legislation and funding have also been passed to directly support and expand upon several of the recommendations initially issued by this task force.

Commission operations

It is also important to establish clearly and from the outset how the commission will operate. For example, will all meetings be public? Will meetings be held in the same place, or will some be held in the field? How will decisions be reached? If not by consensus, and if those decisions will be represented as the opinion of the commission, will there be a mechanism for participants to express dissent? Will the commission have one or more chair(s)? How will that person be appointed or elected? These issues may not be resolved at the point of creation of the commission (whether legislative, by executive order or otherwise), but should be set out at or before the first meeting of the commission.

Conclusion

The creation of a commission or task force may be a valuable way for a state to take an active step forward in addressing issues related to the future of work. It has the potential to create an imperative and define a process for critical cross-sector collaboration on important issues. And it signals that the related set of issues are a priority for the state and its elected and appointed leaders, giving those leaders the opportunity to convene stakeholders and drive progress. However, care should be taken to ensure that a commission or task force process is not used to delay more specific and impactful policy action. In addition, the process carries the risk of exposing or exacerbating tensions that may exist between individuals, organizations or sectors. With careful consideration and thoughtful design, a commission on the task force could ensure that the future of work is dynamic, meaningful and equitable.

Existing models

More information about: Indiana’s Future of Work Taskforce, Washington’s Future of Work Task Force, New Jersey’s Future of Work Task Force, California’s Future of Work Commission, Future Ready Iowa Alliance, Talent Ready Utah executive board, Career Connect Washington Taskforce, and Future Ready MT Cabinet.

About the authors

Libby Reder is a Fellow with the Aspen Institute Future of Work Initiative. Libby is an author of a new report, Designing Portable Benefits: A Resource Guide for Policymakers.

Rachael Stephens is a Program Director for Economic Opportunity at NGA Solutions: The Center for Best Practices. Rachael directs NGA’s work with states on understanding and preparing for the future of work, including the national project Future Workforce Now: Reimagining Workforce Policy in the Age of Disruption and a multi-state collaborative project on understanding and supporting the on-demand workforce.