Asma Abou Ezzeddine Rasamn, Founder of Malaak and Middle East Leadership Initiative Fellow, dedicates her time providing safe settlements for Syrian refugee children in Lebanon. Even before COVID-19 and Lebanon’s current revolution unfolding, these refugees have been living through a pandemic of their own for eight years. Asma shares her experience dealing with one of the most underprivileged communities in the world and puts inequality into perspective. Note: some answers have been edited for clarity.

Q: Can you tell us about the community you are working in?

I work with Syrian refugees on the northern border of Lebanon with Syria, which is an extremely vulnerable region. It’s one of the most underprivileged regions in Lebanon and a region that has the poorest host community. You add to that 250,000 Syrian refugees, and you can only imagine how difficult things are. I’ve built an academic center that is considered a safe space for refugee students to come and not only learn, but actually have experiences in an environment they would’ve never been exposed to because of overpopulation in their informal settlements. It’s an extremely difficult life that these students live. What my NGO has tried to do is advocate for equality and learning. Even for those who live in difficult regions, they still have the right to access education.

Q: You saw the need to help the Syrian refugees that were placed in Lebanon. What pushed you to take action?

I am half Lebanese, half Syrian. I grew up in Damascus, which is the capital of Syria and I lived there for 18 years until I moved to Lebanon to go to university in 1998. I studied developmental psychology so face-to-face communication has always been my passion. In 2011, hell broke out in Syria. And in turn, Lebanon was dealing with one of the largest refugee influxes through its borders.

I witnessed this and thought if anyone can help, it’s me–I call both countries home. I realized that I could be a mediator because I truly understand both cultures.

I’d been living in Lebanon for 10 years before I started my NGO Malaak and I had even never visited that North [where many Syrian refugees were placed]. From afar, I’d watched destructive refugee placement occur in Lebanon due to the lack of government support. The settlements are overpopulated and everyone is trying to fight for the same piece of land. and the same jobs. As a response to the problems I saw, I founded Malaak and started working on the ground to create healthy environments for these people. When I started working there, I realized what the needs were and learned that it takes respect from the host community to create a better life. It takes integration between the two, which had never been done before. I employed Lebanese people to help Syrian kids. And I think that [proximity] is the “magic potion” that helped a lot in my work.

Q: What does Malaak mean?

Malaak means angel in Arabic. I truly believe that I have a lot of angels in my life that push me to do the work that I do. I believe that all the children that live in camps are angels. And I believe that a lot of my donors and supporters are angels.

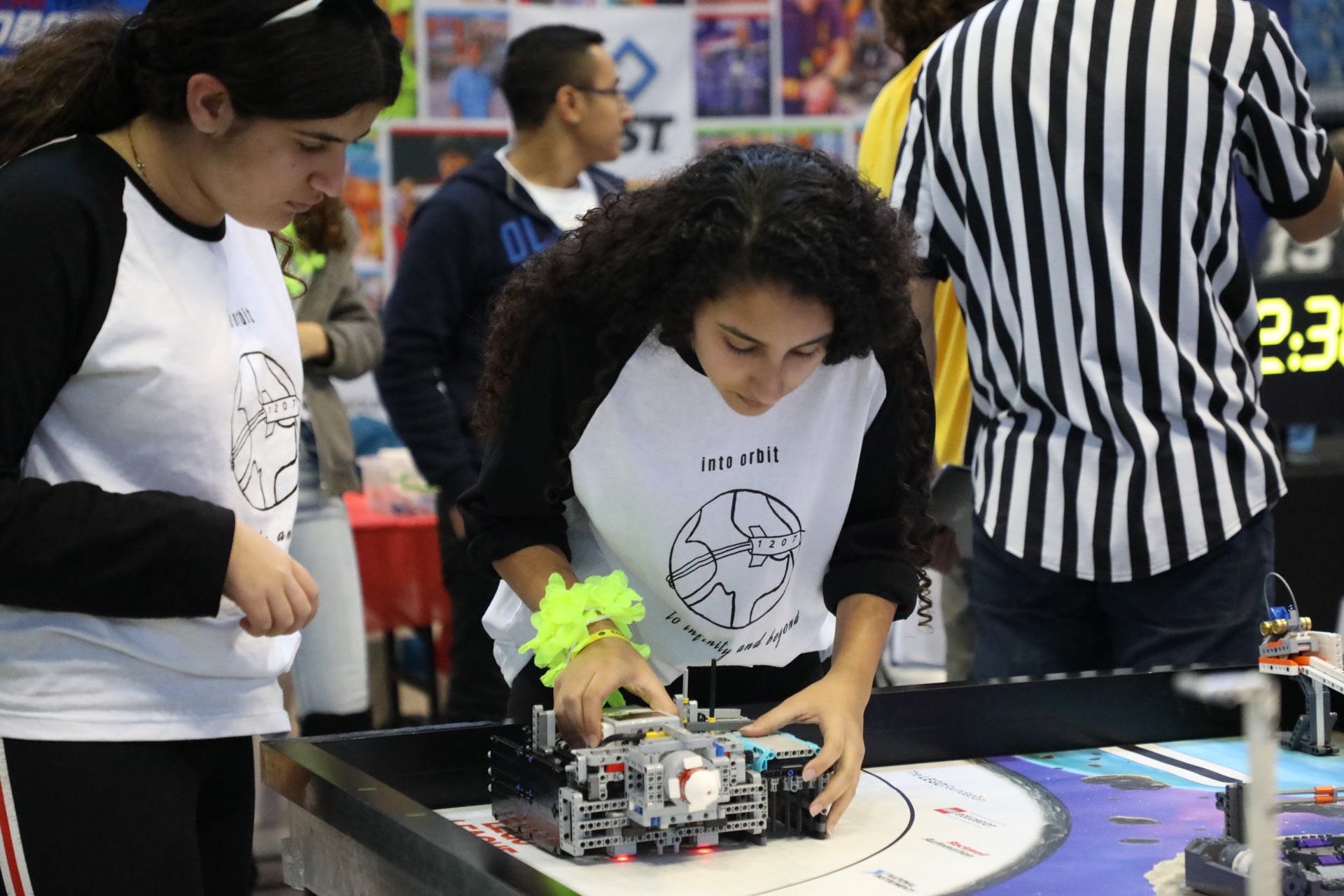

Image: MELI Fellow, Asma, works with refugee children in northern Lebanon.

Q: What has the experience of the pandemic been like for the refugees you serve?

When COVID-19 began to spread in Lebanon, I went to the settlements to announce the shutdown. I was telling the refugees about the pandemic and giving them tips on how to reduce the spread with the basics of social distancing, keeping your hands clean, not leaving your household when you feel sick, and so on… I was approached by one of the members in the settlement who said:

“Thank you for giving us all this information, but we’ve been living in a pandemic for the last eight years. You live in the city, are somewhat privileged, and you are talking to us about something that has not changed our lives one bit. We have been deprived of the freedom to move. If one person gets sick in our camp settlement, we all get sick and the vulnerable die simply from a flu, from a stomach virus, from anything. I think that the COVID-19 is just an equalizer. It’s just made everybody equal, but it changes nothing.”

In terms of injustice, such as what is described above, it is just a part of Lebanon. This is injustice that those in a first world country can’t even conceive. We’re not even fighting for racial rights. We’re still finding ourselves. We’re still fighting gender equality. We’re still fighting early childhood marriage. We’re still fighting underage labor. We’re still fighting for the right to say what we believe in. We have a long way to go.

Q: How do you feel current events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the concurrently unfolding revolution in Lebanon, have changed how you think about doing this work?

Learning is not supposed to be a privilege. Unfortunately, with COVID-19, learning is a privilege because it requires access to high-speed internet and online learning materials. If not, you’re stuck.

When the pandemic hit, we had to close Malaak and deny our students access to the center. But, we knew we had to find a way to reach our students and make sure that could still learn and moreover, that they remain safe. Our mission is to be able to keep our students out of these dangerous and high-risk settlements.

We decided to new program: The Right to Learn, to respond to the new need for technology. We are distributing one tablet per family to give access to the needed technology for education.

Q: How did you decide to implement the use of new technology resources?

We decided we could not distribute them without having a plan in place. So often, NGOs latch onto trends, such as technology where they distribute tablets, iPads, and laptops but never follow-up with the communities. But this is often without an understanding within the community about how to utilize the resource or why they are being distributed. 80% are of the refugee community Malaak serves is illiterate, so we decided to keep the tablets at our center and determined a way to safely let very small groups come in to take their tablets and to sit down for an informative session on how to use them to ensure the technology becomes an effective learning method.

Image: Young refugee girls show their appreciation of Asma’s NGO, Malaak.

Q: How do you maintain your moral conviction in the face of uncertainty?

We’re a culture that’s built on so much resilience. Even as I trace back to my grandparents’ generation, they talk about leaving the country once, twice, three, four times, and how they had to stop their business and start over again. This pattern occurred again in my parent’s generation and now again with mine. So, I just think that there is power knowing there’s always a plan B – that there’s something better to come after a crisis. Even if there isn’t, you have to make use of what you currently have. And that’s why Malaak decided to go virtual, no matter what it takes. We will provide our kids with education.