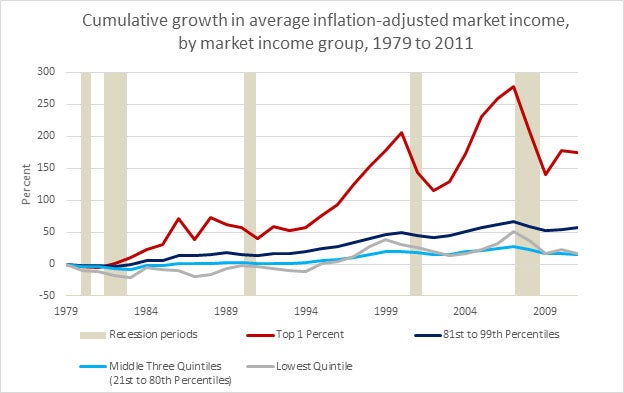

How do we address widening income inequality in America? Income inequality has widened considerably since 1979. Using data provided by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the figure below shows the increase in average (real) incomes for each quintile of the population from 1979 to 2011. While often times the perception is that income inequality has widened because people at the bottom and middle quintiles have experienced a loss in incomes over time while the top 20 percent have increased incomes, this is not true. Rather, average incomes have been rising across the board. However, incomes for the top quintile have been increasing at a much more rapid rate than incomes at lower quintiles. Households in the bottom four quintiles experienced increases in incomes that averaged 16 percent over this period. The significant income increases occurred at the top, especially the top 1 percent, where labor and business income grew by more than 200 percent and 450 percent, respectively.

So what steps can we take? The question for policymakers is whether we should focus on restraining the growth of incomes at the top or adopt policies that directly help boost incomes at the bottom. To the extent that incomes at the top are earned through unfair means, there is no denying that we need to fix the corruption that allows this type of rent-seeking and leads to concentration of income and wealth in the hands of a few. However, as academic research has shown, it is also true that such income concentration is often the result of a successful innovation or enterprise, or occurs because of superstars in the field of sports or entertainment. As Nobel Prize winner and economist Angus Deaton recently noted, “some of the greatest inequalities have come from the greatest successes.” Where income increases occur due to these types of reasons, inequality is inevitably a consequence. Policymakers could respond by increasing tax rates and redistributing more. But, given that the top 1 percent already pays more than 40 percent of all federal income taxes according to the Tax Policy Center, and the U.S. spends about $800 billion annually on anti-poverty programs, the potential to bring about a significant change in our tax and redistribution system appears limited. In fact, a recent analysis by the Tax Policy Center shows that even a significant increase in the top federal income tax rate is unlikely to make a dent in income inequality.

I would argue for a more direct approach to tackling the problems of the poor. Poverty is often the result of a lack of education, a lack of skills and ultimately a lack of work. In their recent work, economist Raj Chetty and co-authors argue that poor economic mobility or the inability to move up the income ladder often arises from factors like residential and racial segregation, and growing up in a household headed by a single mother. Therefore addressing the issue of schooling, access to jobs and changes in family structure is key to reducing income inequality.

We may be able to prevent the persistence of poverty across generations that has contributed to the lack of economic mobility in the U.S. if we can: help poor children get into good quality schools perhaps through school choice programs; allow young adults to get the skills training they need to get good jobs; expand paid apprenticeship programs; and adopt policies that discourage unwanted early pregnancies in unmarried women.

At the recent Aspen Institute Summit on Inequality and Opportunity, this issue was directly addressed by the panel of high school students, who reiterated that what they valued more was not the equalizing of incomes, but the equalizing of opportunities. They most appreciated having the same access to good schools, good jobs and good neighborhoods as those with higher incomes. They wanted the opportunity to prove that they could rise to the top of the income ladder through their own hard work, education, skills and eventual success.

I think this is an important lesson for all of us in policy. Government actions can either directly help the poor and disadvantaged through tax and transfer programs that aim to “equalize” incomes or they can work indirectly by improving access to good quality schooling and jobs. Focusing on the latter, even though the real gains may show up only in the long-term, is often just as critical as helping the poor and needy today.