What if accomplished business leaders applied their entrepreneurial talents, networks, and collective brainpower toward building a better society? What would the world look like?

That world is exactly what the Henry Crown Fellowship—the Aspen Global Leadership Network’s flagship program—has been building for the past two decades. The Fellowship develops community-spirited leaders, giving them the tools—and the nudge—they need to meet the complex challenges of business and civic leadership. Each year’s class of 20 Henry Crown Fellows has already achieved considerable success, generally in the private sector. They are all beginning to look toward the broader role they might take on in their communities. “The Fellowship gives diverse leaders the head and heart space to reflect on leadership and impact when they are at an inflection point in their lives,” says Tonya Hinch, a 2007 Henry Crown Fellow and the program’s managing director. “They begin their journey of moving from success to significance.”

Over the course of two years, Fellows attend a structured series of four week-long seminars. The first, “The Challenge of Leadership,” in Aspen, Colorado, focuses on the qualities of leadership necessary to master the forces of change. At the end of the first week’s seminar, each incoming class votes to give itself a name to capture the spirit of the class as they first discover their new compatriots and to serve as a guiding philosophy. The second, the classic Aspen Executive Seminar, at the Wye River Conference Center in Maryland, gives Fellows the opportunity to explore the “Good Society” and to learn how to make it a reality. In the third, “Leading in an Era of Globalization,” Fellows meet with other Fellows from across the Aspen Global Leadership Network—be they from Latin America, India, China, Africa, the Middle East, or South Carolina—to explore clashing values in an ever-more-entwined world. The final seminar, “The Promise of Leadership,” allows Fellows to explore issues around legacy and life balance and to plan for their future as a class.

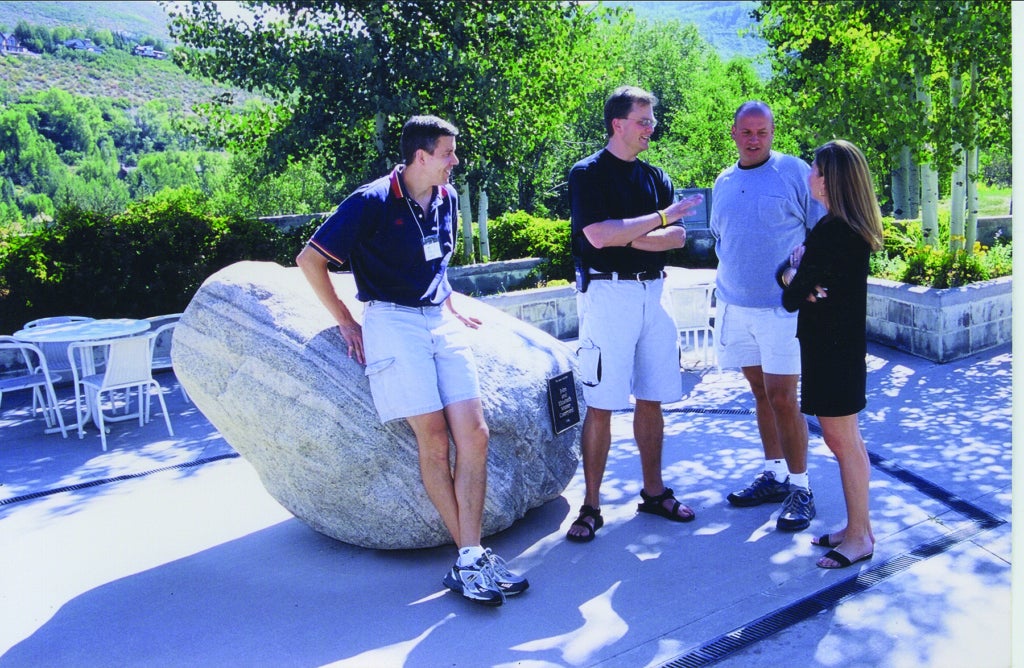

2002 Fellows Arne Duncan, Stace Lindsay, Russ Pillar, and Joanna Rees at their first seminar: The Challenge of Leadership, in Aspen.

Kristen Grimm, a 2014 Henry Crown Fellow, recalls her first experience with the Fellowship: “I had no idea what I was getting into.” Grimm, the founder and president of Spitfire Strategies, says that “it all became clear” within a week: “I was going to rethink everything—what I valued, what I stood for, who I respected, and the many assumptions I had come to hold as truths.”

It was a lot to absorb. Yet Grimm says that the Institute—and the setting of Aspen itself—”made all of this soul-searching engaging rather than torturous. I laughed more than I had in a long time.” Now, three years later, she says, “The experience is without rival.”

Nothing Ventured, Nothing Gained

All Fellows are required to design and launch a leadership venture—a project that addresses what they identify as the foremost social, economic, and political challenges of their time. It’s expected that Fellows will apply the leadership practices they hone during their Fellowships to do the kind of galvanizing work they had always meant to do—but never found the time for. Many have been so successful that in 2007, Institute Trustee Anne Welsh McNulty established the John P. McNulty Prize to recognize the strongest ventures around the Aspen Global Leadership Network and amplify their impact. Given the variety of Fellows, leadership ventures take myriad paths. But they all have one thing in common: a fresh approach. Ventures offer a chance to be bold. To take a risk.

Putting a pair of eyeglasses on every low-income child in the country, for instance, may sound ambitious. But that’s the kind of impact Henry Crown Fellows aspire to. Dave Gilboa, a 2014 Fellow and the co-founder and co-CEO of Warby Parker, created a program with a mission to provide better vision for students in need.

Gilboa and his team started in their own backyard, working closely with the city of New York and its Community School Initiative. Warby Parker estimates that though 20 to 25 percent of New York City public-school students have vision problems and require optometric testing and glasses, they don’t have access to testing or can’t afford it. If children could see the board and (literally) focus in class, the team reasoned, they would be more motivated to attend class and to pay attention, and ultimately be more prepared to succeed. With Gilboa’s leadership, Warby Parker launched a four-year program to distribute more than 20,000 eyeglasses to children in New York City. Warby Parker has since launched a similar program in Baltimore, providing glasses to more than 8,000 students in 150 public schools. The company has also teamed up with Johns Hopkins University to conduct a study to understand the correlation between vision treatment and reading scores. Johns Hopkins will publish the study’s findings with the aim of influencing public policy at the federal level.

Assembling the Mosaic

The Institute’s Henry Crown team considers about 400 candidates each year, looking for clear evidence that candidates are at the right point in their lives and careers to stretch their leadership. The commitment is not just for four seminars over two years but also the time to launch a meaningful venture—and an expectation that Fellows will remain engaged with the Henry Crown Program the rest of their lives.

Assembling the mosaic of Fellows is like building an orchestra, says Keith Berwick, the former executive director of the Henry Crown Fellowship: “You don’t need 16 violinists, even if they are the most fantastic violinists you have ever heard. You need to make sure that there are different voices at a table.” The team thinks about diversity in a methodical way. A typical class will have a mix of traditional entrepreneurs, like Reed Hastings (1998), the creator of Netflix, or Reid Hoffman (2010), the co-founder of LinkedIn. But there will also be someone like Blair Christie (2015), the former senior vice president of Cisco, an “intrapreneur” now working on a venture to rebalance the gender ratio in private and public boardrooms.

Civic-Minded Leaders Will Change the World

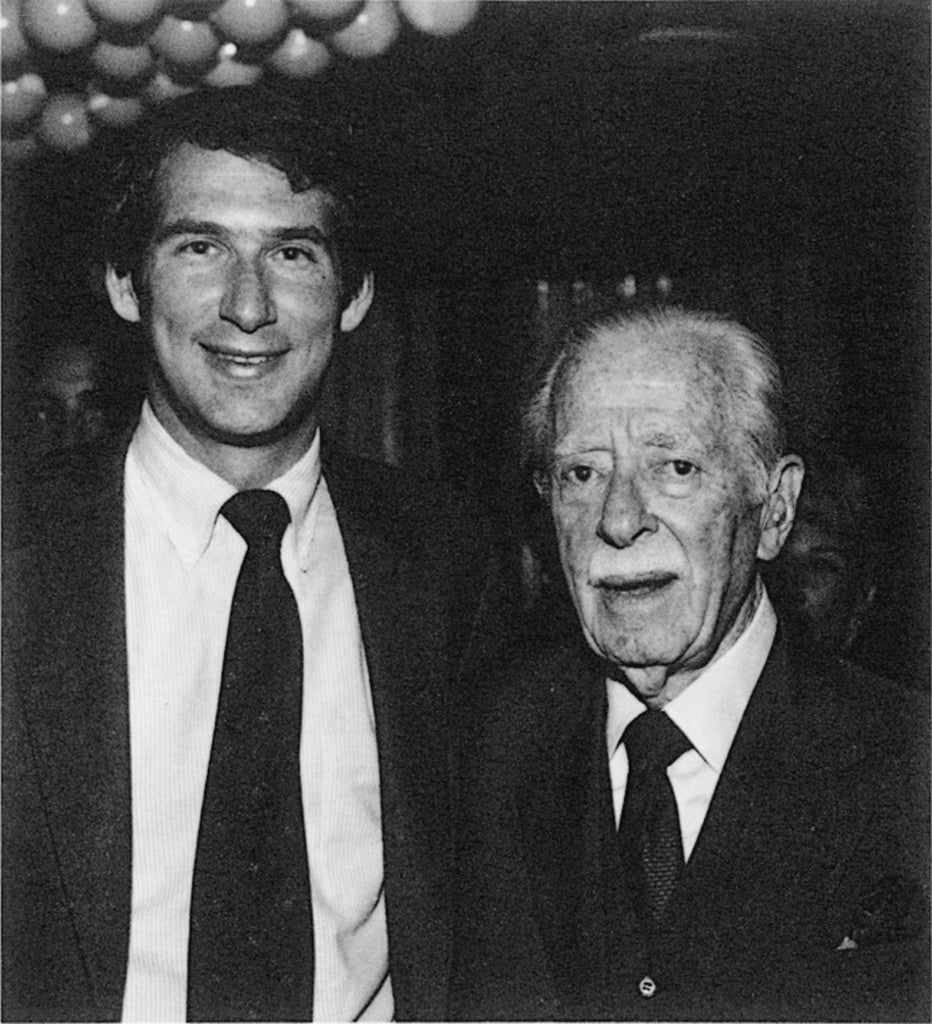

Current Aspen Institute Board Chair Jim Crown with his grandfather, Henry Crown.

The values embodied in the Henry Crown Fellowship honor the memory of Chicago industrialist Henry Crown, whose career was marked by a lifelong commitment to integrity, industry, and philanthropy. One of his guiding philosophies was that changing the world requires civic-minded business leaders. Government, he reasoned, couldn’t address all of society’s issues—and so he held himself and his company responsible for making up the difference. When he died, in 1990, longtime friends Francis and Muriel Hoffman teamed up with the Aspen Institute to launch the Fellowship. The Crown family, which has been involved with the Institute for almost two decades, also takes pride in the Fellowship. When Fellows “graduate,” Lester Crown, Henry’s son, invites Fellows to embrace their broader roles in their communities. Jim Crown, Henry’s grandson, serves on the Henry Crown Fellowship Board of Overseers in his current role as chairman of the Institute’s Board of Trustees.

Program founders Francis and Muriel Hoffman attend the Aspen Institute Annual Award Dinner in New York.

Peter Reiling, a 1998 Henry Crown Fellow and the current executive director of the program, made it his leadership venture to expand the Henry Crown Fellowship into what is now known as the Aspen Global Leadership Network. Teaming up with other Fellows to launch new programs, the network now comprises 2,500 Fellows in 14 Fellowships spread across sectors—including education, health, finance, politics, and the environment—and across more than 50 countries. Each initiative is modeled on the original Henry Crown Fellowship Program.

“Building this incredible community has become my life’s work,” Reiling says. “And what’s been so fun is all those who have joined me to make it a reality. I can read the news on any given day and see the positive impact our Fellows are making.”

Looking Toward the Future

The Henry Crown team continues to look forward. The key question, Hinch says, is: How do we keep the Fellows meaningfully engaged—and, as Bill Mayer, chair of the Henry Crown Board of Overseers asks—to what end?

The answer to Mayer’s question comes in the ways Henry Crown Fellows use their talents to build the Good Society. Fellows start companies with a mission to both do well financially and to give back: David Ebersman (2000) and Bryan Roberts (2006) launched Lyra Health, a behavioral-health technology company that connects people who have health conditions to providers and treatments, for example. They step out of business careers into public service: Deval Patrick (1999) served as governor of Massachusetts, Sylvia Burwell (2005) as secretary of health and human services, and Cory Booker (2003) as one of the current US senators from New Jersey.

They join company boards and government advisory councils: former Vice Chairman of Goldman Sachs Suzanne Nora Johnson (1998) serves on the boards of Pfizer, Intuit, AIG, and Visa, helping build board diversity and serving as a role model to women throughout Wall Street; Preeta Bansal (2009) was named to Barack Obama’s advisory council on faith-based and neighborhood partnerships.

“The Fellowship is not something you do,” says Tim Noonan (2008), a vice president of the Boeing Corporation. “It is something you become. Through the readings, the dialogue, the friendships, the community, I became a Henry Crown Fellow—more open, aware, giving, responsible, and alive than I thought I could be, changed on the inside forever.”