Whether you were rich or poor, sharing came as naturally as sunrise to the people of Madison Park. You’d see tractors, plows, and other implements that belonged to one family parked in someone else’s backyard for weeks. Daddy’s close friend Ray never felt compelled to buy a lawnmower, and Daddy implored him not to, because his yard was so small and our mower was available. If someone’s roof leaked, half a dozen men would descend on the house one Saturday and reroof it, with no money changing hands and no one keeping score. You always planted a bit more in your vegetable garden than you needed.

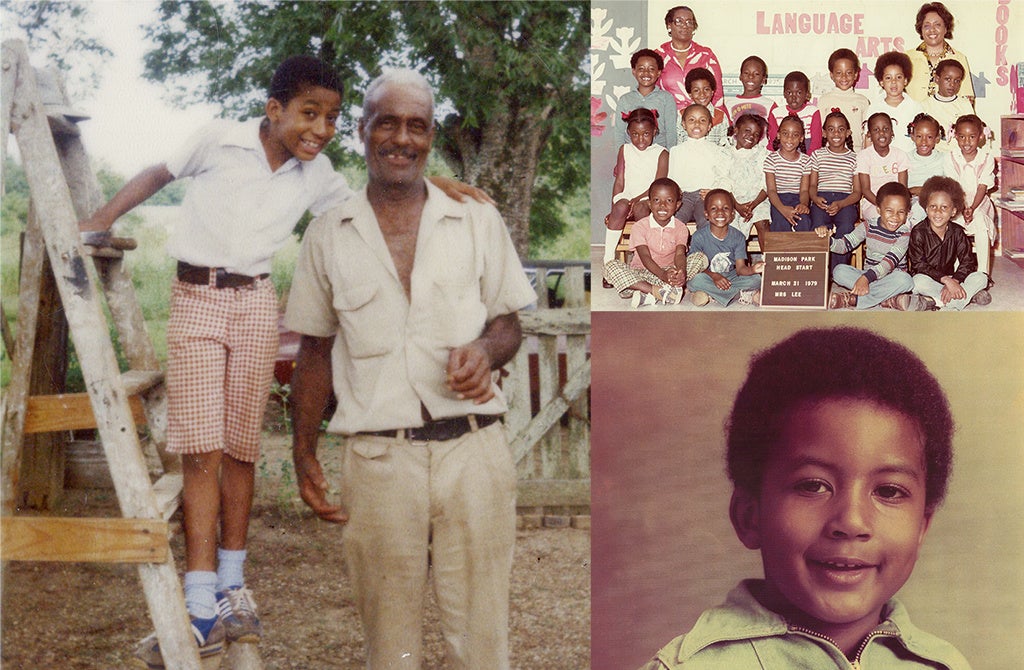

But my arrival had a price tag that neighborly generosity couldn’t close. Anticipating the extra expense of raising a child, Mama and Daddy sold the bit of extra land they owned. During my mother’slast years in high school, they’d scaled back the number of days and hours they worked. But when I came along Daddy took extra carpentry jobs, and Mama, a maid who kept house for white families in the Old Cloverdale neighborhood in Montgomery—a section of beautiful homes with carpet-pressed lawns and sculpted hedges where Zelda and F. Scott Fitzgerald once lived—stepped up her schedule.

Madison Park elders feared that forced integration would destroy their model of community-based education, which assured that every student was taught by someone who knew his or her background, parents, and family situation. Given that blacks and whites in the South lived separately, integration required transporting students to schools outside their neighborhoods. While elsewhere busing might have helped achieve greater diversity, Madison Park’s citizens had felt insulated from the abuse of segregation common beyond their boundaries. Thus, they feared that the stability they’d achieved, while not perfect, might be better than the unknown. Aunt Shine once told me, “No one cared for our poor students like we did.”

In the pre-Brown days, and long before schools offered free breakfast and lunch, the teachers often fed their hungry students. When boys and girls came without winter coats, they bought them clothes. When kids didn’t come to school, the teachers went out looking for them. They were in and out of students’ homes and ran into them at church, ball games, and at Mr.June Jackson’s grocery store. Fearing this spirit of community would be lost, they also feared the children would be failed by a system based on statistics instead of relationships.

But the law was the law. I was bused to a school in Montgomery, twenty minutes away.

When I was just seven, neighbors began to hire me for odd jobs so I could save up to pay for my education. I mowed lawns, trimmed shrubs, picked blackberries, and stacked fireplace logs. Over time, my monthly calendar expanded to include picking up litter, picking pecans, peeling pears and peaches, weeding vegetable gardens, watering flower beds, cleaning barns, organizing storage sheds, piling bricks, and painting garages. I realized even then that my employers could easily have done the work, but they hired me to put cash in my college fund.

I would just as soon have been given the money outright, but Mama insisted that I earn my way. She believed I would feel better about myself if the rewards were a product of mysweat. Looking back, those folks knew exactly what they were doing—the back-breaking jobs I endured built in me a powerful desire to find a better way to make a living and ratcheted even tighter my resolve to get a university education.

One day after cleaning out her parlor, Mrs.Peabody, the woman my grandmother worked for in Montgomery, asked Mama, “Mamie, do y’all have a record player? If you do, take these records home to give your little boy something to listen to.”

Mama lugged her ten records home in a wooden vegetable crate, some still unopened. It was summer, and I took my time uncrating my present. I examined each record one-by-one until I found two or three whose covers I really liked. Daddy, as curious as I, brought the record player out to the back porch and plugged it in. “What are you going to play, son?” he asked, reminding me how much he also liked music. I turned the volume up as high as it would go, and the three of us waited.

I didn’t know that what I had decided to play would forever change my life. Out came the most transcendental and wondrously strange sound. It was the voice of the soprano Jessye Norman singing Richard Strauss’s “Four Last Songs.”

I’d never heard such a voice—it enveloped me. The dogs and chickens seemed to hush, and the clanking of tractors plowing faded to the background. Even my normally voluble grandmother said nothing. The look on my face must have stopped her. I was transfixed. Norman’s voice was so refreshingly different andnew to our surroundings that in minutes Bimp, Boo-Boo, and Rod raced across the yard, landing with a thump on the porch. “What you listening to, Bugs? What is it?”

They weren’t ridiculing me or scoffing at the music but expressing wonder. How could the human voice create such a sound? How could it sway back, turn curves, and climb so high? I played that record at full volume every day for the whole summer, and no one complained.

Eventually I played all of Mrs.Peabody’s records, but the Norman album touched me most. It wasn’t until years later that I learned that she was black, grew up in Augusta, Georgia, and got her start singing in the church choir. After many years of listening to that album, I truly appreciate what enormous range she possessed, what impeccable control and phrasing she exercised in her singing. But sitting on the back porch with my grandparents, I never could have imagined that one day I’d receive an invitation to dine with Ms.Norman in Aspen, Colorado, and tell her the story of how I came to love opera.

Copyright 2017 by Eric Motley. Used by permission.