Take 450 presenters, drop them in various combinations into 400 sessions on 12 very broad themes over seven days, then serve the resulting mix to thousands of attendees. Add speakers who bring a matchless depth of experience in their fields to the table and the stage; this year’s tracks covered freedom of speech, the art of justice, staying human in a high-tech world, the genius of animals, and an examination of the American union and global geopolitics. Add to that a 3,000-strong audience—many of them top thinkers and leaders in their own right—and include 300 action-oriented young scholars from all over the world plus 30 high-school students and educators from the Bezos Scholars program. You have the Aspen Ideas Festival.

Important questions were raised in every room, every campus pathway, and on seemingly every corner of downtown Aspen, where the conversation often continued. How should we relate to each other in these divisive times? How are social media and the ways we consume news fueling polarization? How can the personal, visceral stories of students from Parkland, Florida, and inner-city Chicago spur action on the complexities of gun violence? How do we resolve US-Mexico border tensions? Will the #MeToo movement spur meaningful policy changes? How do we shelter the millions of refugees from the global migration crisis? And can animal behavior inspire one to think differently, dream for a better existence, and even change the world?

“Big ideas don’t just happen,” Fred Dust, a senior partner at IDEO, said at the opening session. “Big ideas are nurtured. They are engaged, fostered, and raised by communities.” In the following pages, we offer just a taste of those big ideas.

“A Great Global Force for Good”

Dan Porterfield, the Institute’s new president and CEO, spoke with David Bradley, the chairman of Atlantic Media, about what the future holds and why he took the job.

Bradley: Dan was coaching young people when he was in high school. He set up two mentoring programs while he was at Georgetown that still exist. He went into undergraduate education, both as a teacher and as the president of an undergraduate school. You have devoted your entire life to youth. I don’t know if you’ve looked at us, Dan, but for some of us, the last time we were in school was the Coolidge administration. What were you thinking?

Porterfield: I’d like to channel my mentor, Father Tim Healy, who had this beautiful line that I quote a little differently each time I say it: “The young dream, and the old teach. In that mystery comes a tomorrow that we who are older will not see but will have helped to shape through the lives and work of our students.” All of us are called to be educators and mentors to the young. Every single one of us, always, until we say goodnight. Our human calling is to invest in the young.

The Aspen Institute is this great global force for good that Walter Isaacson and all of you helped to build. Our best days, in terms of social impact and improving the quality of life for the one and the many, are still ahead of us. What I’m hoping to do with you is to build on this incredible resource to promote human flourishing in all the ways that has to happen—intellectual, personal, social—as citizens, as members of the human family, together. We are all called by the example of those who have come before us to make this Institute as important and results-oriented as it can be. Not just for us, of course, but for the entire country and world. We are at a moment when it feels like centrifugal forces are pulling us apart. But the truth of the matter is it’s a centripetal calling that we all feel to be one. This Institute can enact change in still more dramatic ways by focusing on framing and solving problems in a way that helps everyone.

“Higher Ground”

For decades, artist Carrie Mae Weems has created art that probes politics and power. At the festival, she staged a performance and then discussed how her work merges the personal and the political.

Weems: I don’t deal with the history of violence constantly because I want to, but because I am compelled to: by my background, my culture, my concerns, my skin, the way in which I have been marked by time. There is a great tradition of artists involved in activism. Today, we started with this idea: the personal and the political. For me, there is no difference in my life between the personal and political. It all blends. I do the work not because somebody is paying me to do it. I’m not doing it because “social justice” is trending on social media. I do it because the work really impels me.

I had this incredible dream. It was a hot August night, and I dreamt that a tsunami was coming. I saw this massive wall of water just rising up and threatening to take us all. In my dream, I knew I had to warn my friends that this huge thing was coming, and it’s about to swallow us and destroy us, overtaking the land. I started running, and just as I began to run, I turned, and there was Donald Trump—leering at me. Fabulous. I ran past him, and I ran toward my friends, saying that this tsunami was coming, we had to protect ourselves. I came to a point where there was a great ladder. I saw all of my friends climbing this ladder, and as they climbed, they were singing, “We’re climbing Jacob’s Ladder.” It was not a hymn but this extraordinary protest song.

I knew then that part of the work I had to do was to figure out how to get to higher ground. How to get to higher ground, how to see what this moment is, how to think about it, how to talk about it, how to negotiate it, how to write about it—and then how to make work out of it. That’s my project. So for me, the political is personal, and the personal is always political.

We’re always grappling with that idea. What matters at any given moment, as you are shifting, developing, and processing, is how to enter your work in a way that allows you to build on this sustained dialog that you are having with yourself, with the meaning of your life. I have been completely, for years, buried in snaking through these ideas about structures of power. Right now, I’m looking at that in relationship to violence. It’s an interconnected way of working, of seeing the world and understanding your place in it, and what you have to give voice to through art. In one way or another, we are all involved in questions about art and justice. This is a crucial moment, but we’ve been doing this work for a very long time.

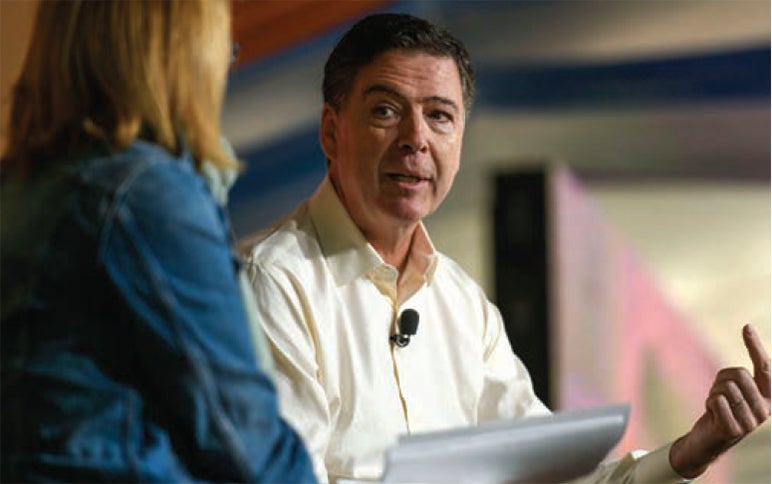

Comey’s Choice

Former FBI director James Comey sat down with Katie Couric to examine the tough decisions he faced in the run-up to the 2016 presidential election.

Couric: On July 5, 2016, you held a press conference announcing you were not recommending charges against Hillary Clinton. You were not the attorney general, you weren’t even a prosecutor. Why was it appropriate for you, as the investigator, to make that announcement? Comey: It’s always the attorney general who announces, and the FBI director is typically standing next to her. The reason I did it was I thought it was between two options: offering transparency separately or offering it standing next to the attorney general. The option least likely to do lasting damage to the institution was the first bad option. There was a lot of controversy during the final week of the investigation, when Attorney General Loretta Lynch had a meeting with Bill Clinton on an airplane. There was a storm about whether that fatally compromised her. I worried about the public perception that the investigation was not done credibly. Lynch announced, without talking to me, that she would accept my recommendation and that of the career prosecutors. I don’t know what option I had then besides choosing either the traditional thing, or doing something I never imagined, which was to announce the recommendation she said she would accept separately. This was the result best calculated to maintain the faith and confidence of the American people and end the investigation in a credible way.

Couric: You called Hillary Clinton’s behavior “extremely careless,” placing a value judgment on her. Can you give me another example of an FBI agent or prosecutor publicly maligning someone they’ve decided not to prosecute? Comey: Lois Lerner, the IRS executive. The Justice Department described her as a “poor manager” but not engaged in criminal wrongdoing when they closed the investigation of the so-called targeting of the Tea Party. Also José Padilla, the “dirty bomber,” in 2004. The department made a public announcement of why he had been detained and not prosecuted and described in great detail his conduct. It is the norm to do that when the public interest requires it. There’s no doubt the announcement falls well within the conduct of the department. I wasn’t trying to attack Clinton. I was trying to be transparent with the American people.

Your Brain on Tech

The Center for Humane Technology’s Tristan Harris came to make a point: automation is an existential threat to humans.

Harris: We have this narrative that technology’s just a neutral tool; we can do whatever we want with it. That is completely not true. The technology we have right now is purpose built and designed to capture human attention. How much have you paid recently for your Facebook account? Zero. Their business model is to capture your attention and sell it to advertisers—and they have a bunch of techniques to get people hooked. On top of this, you have automation. On Facebook, there are millions of items they could show you, but they pick the things that are going to keep you hooked. About 70 percent of YouTube’s traffic comes from recommendations from their “up next” feature. And because the goal is capturing people’s attention, it’s going to select the thing that will most likely keep you on YouTube for the longest amount of time. The biggest supercomputers in the world are inside Facebook and Google—and they’re pointed at two billion people’s brains.

When Garry Kasparov played chess against IBM’s Deep Blue, he lost. Why? Because even though Kasparov has the best human mind for chess, the computer can still see way more moves ahead. It’s game over. There’s never going to be another human to beat computers at chess. You now have 1.9 billion human animals dropping into YouTube, and a supercomputer is activated to play chess against their minds, asking, What’s the perfect video I can show you that’s going to keep you here the longest? That’s why we say, “I’m gonna watch this one video,” and then wake up two hours later like, “What the hell just happened?” It’s like bringing a knife to a space-laser fight.

The political consequences are alarming. There’s an intrinsic bias toward conspiracy theories, radicalizing content, and divisive material. So if you drop into a normal 9/11 news video and then watch what’s on autoplay, two videos later you’re watching 9/11 conspiracy theories. If you drop a teen girl into a dieting video, two videos later she gets anorexia videos. It’s on Facebook, too: if you join a mommy group, they suggest other groups that are good at keeping people on Facebook: anti-vaccine conspiracy groups. Automated systems are driving what 2 billion human animals are being led to and believing—and there’s no one home.

It’s not as if there’s someone at YouTube or Facebook who wants this to happen. It’s an automated system pursuing a naïve goal: capture attention. And it’s producing everything from a doubling rate of teen suicide in young women to radicalizing conspiracy theorists. YouTube recommended Infowars conspiracy-theory videos 15 billion times. This mind influence is jacked into people everywhere in languages the engineers don’t even speak. Then in sensitive markets, genocide is amplified because systems are recommending fake news videos that amplify ethnic tensions between, say, the Rohingya and Myanmar. The consequences are vast. This is an existential threat that’s outpacing the human control loop of our choicemaking capacity. It’s steering world history right now. And we have to fix it.