Alot of people still do not trust in Mexico’s democracy. During this past election season, as the results of the polls were released, you could sense the unease, the lack of faith in institutions. Some people feared that if their preferred candidate did not win the election, instability would take over the country. Others suspected that the entire system was compromised.

Alot of people still do not trust in Mexico’s democracy. During this past election season, as the results of the polls were released, you could sense the unease, the lack of faith in institutions. Some people feared that if their preferred candidate did not win the election, instability would take over the country. Others suspected that the entire system was compromised.

In Mexico, this doubt is reasonable. In certain circumstances, even suspicion is warranted. The real danger, however, is not doubt or suspicion; the real danger is an open intolerance for an opponent’s ideas and for the democratic process itself. The popular will cannot be despised even when the party and its leader are far different from previous administrations. These are times to respect popular will and to defend democracy—not to underestimate or ignore it.

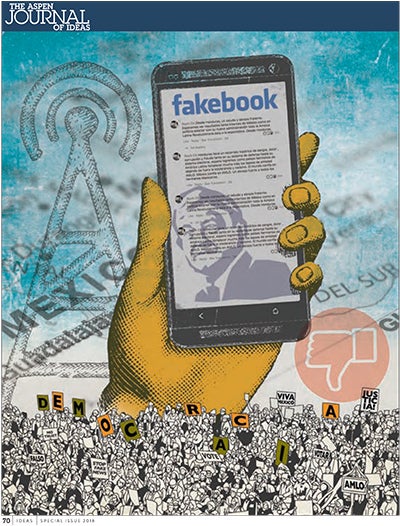

One cause of this tension in the electorate was the deluge of political social media that Mexicans were exposed to, an unpredictable and noisy stream of crossed messages from anonymous authors with imperfect information and ulterior purposes. Political adversaries aimed to discredit one another no matter what it took and no matter what ethical lines were crossed. The unconscious, knee-jerk need to win overwhelmed engaged thinking and productive debate.

Operating on political autopilot, voters’ actions did not always match their core beliefs. It’s a theme the Mexican novelist Carlos Fuentes explored in The Good Conscience: he contemplated whether it is possible to fix the flaws in established institutions while still retaining one’s integrity. Today, in every corner of Mexican society, integrity and politics clash. Many people wanted to democratically vote into power a selective, authoritarian, and classist regime. Even as they fervently defended freedom, they were incapable of accepting that freedom itself can be interpreted in very different ways. Some were simply tribal and could not accept those who did not share their values. Some were impoverished and harbored a deep and painful ignorance; importantly, they had also never once seen the government’s promises for better opportunities come true. All of this put the well-educated and well-informed—and more privileged—voters at a disadvantage.

In a country like Mexico, so corrupt and so unequal, who decides what’s fair and what’s not? Those who live in comfort and want more, or those who barely survive and just want a decent salary and a measure of respect? The majority of Mexicans fall into the latter category. It was clear before Election Day that if they voted, they would win—even as the elite tuned out their restlessness. The portion of Mexican society that felt offended by the status quo had reached epic levels. And so, Andrés Manuel López Obrador—the nationalist, populist firebrand who has drawn comparisons to Donald Trump—won the presidency.

Yet López Obrador’s surprising ascension does not betray the tenets of liberal democracy. It means only a political change. Liberalism is fundamental to new technologies, innovation, and individual difference. It is also fundamental to new ideas. After watching their country suffer from an unstoppable and unpunished scourge of violence for 12 years in a row, voters demanded a change. Mexicans honored their democracy participating in elections this July. The votes of the poor had the same power as the votes of the rich. The votes of the young had the same power as the votes of the old. The votes of the wise had the same power as the votes of the unenlightened. In a democracy, there is no reason to fear change.

Nevertheless, in a mature nation, mistakes have to be corrected. In order to do so, institutions have to be strong, not weak. Prosecutors and courts have to be autonomous, media have to be independent, and there has to be freedom for all and not just for a minority. This doesn’t describe Mexico today. But it could. Now more than ever, Mexicans would be wise to start conversations with different parts of society. Bankers should talk to students. Entrepreneurs should talk to academics. Rural people should talk to urban dwellers. The rights of minorities, indigenous people, women, and children should be consolidated. And the vacuity of the social-media frenzy must be countered with reason and fair-minded values.

The fight has to be against intolerance, not against the will of the people or, worse, against dissent—dissent, above all, is a privilege of freedom.