How the Bauhaus and Herbert Bayer Shaped the Institute

“The Bauhaus idea of community is so powerful now— the idea of people who disagree with each other being within the same building. We need people to stay within the same building and disagree with each other. That’s the kind of utopian community we all want.”

“The Bauhaus idea of community is so powerful now— the idea of people who disagree with each other being within the same building. We need people to stay within the same building and disagree with each other. That’s the kind of utopian community we all want.”

The speaker was 2019 Harman/Eisner Artist in Residence Edmund de Waal, the best-selling author of The Hare with Amber Eyes, whose ceramics are exhibited around the world. The setting was Bauhaus: The Making of Modern, a two-and-a-half day celebration marking the centennial of the founding of the German art and design school. Presented by the Society of Fellows, the program was the capstone of a year of exploring the legacy of one of the past century’s most influential, if shortest-lived, design schools, which both defined and changed generations of design thinking.

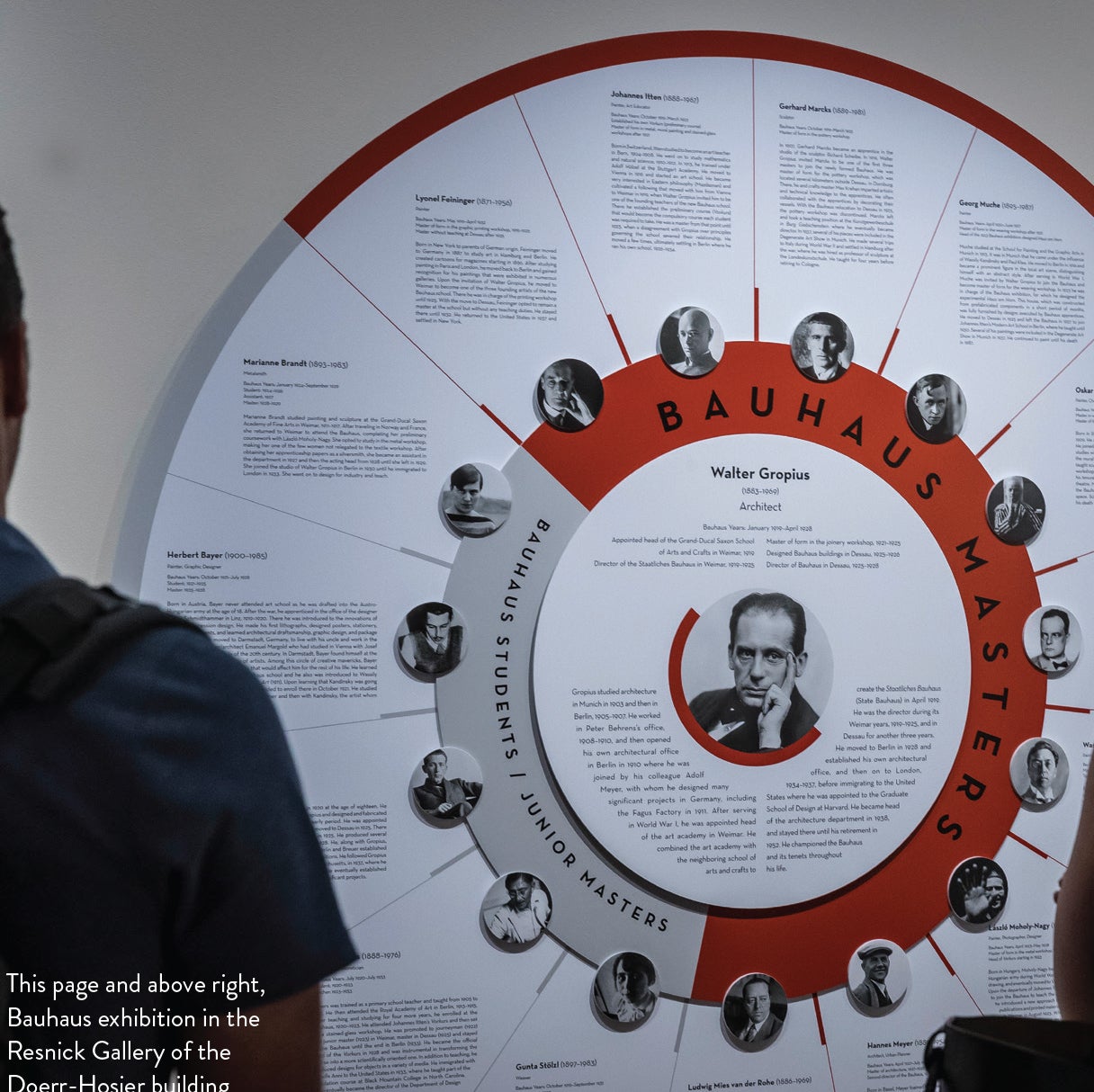

The celebration was appropriately held on the Aspen Institute campus, designed by Herbert Bayer, the Austrianborn multidisciplinary artist. The campus is Bayer’s masterpiece—his Gesamtkunstwerk, or “total work of art,” according to Bernard Jazzar, the curator of the Lynda and Stewart Resnick Collection and of the comprehensive, innovatively conceived Bauhaus centennial exhibition in the Institute’s Doerr-Hosier Center.

The celebration was appropriately held on the Aspen Institute campus, designed by Herbert Bayer, the Austrianborn multidisciplinary artist. The campus is Bayer’s masterpiece—his Gesamtkunstwerk, or “total work of art,” according to Bernard Jazzar, the curator of the Lynda and Stewart Resnick Collection and of the comprehensive, innovatively conceived Bauhaus centennial exhibition in the Institute’s Doerr-Hosier Center.

Both physically and programmatically, De Waal told the gathering, the Institute “was an attempt to create a new kind of space in postwar America, where all kinds of people would be able to sit around these extraordinary tables”—hexagonal, Bayer’s design solution to eliminate any hierarchy—“together, creating a liminal space. And it remains radical today.”

The timing of the conference, with its scholarly and sometimes provocative consideration of the Bauhaus legacy, could hardly have been better: it immediately preceded the announcement of a $10 million gift from Lynda and Stewart Resnick that will both celebrate and change the history of the Institute—the Resnick Center for Herbert Bayer Studies, in a new study center to be built on the Institute’s campus (please see page 20).

Transformative in its influence on art, architecture, and design around the world, the Bauhaus was housed in three German cities—Weimar, Dessau, and Berlin—from 1919 until it closed under Nazi regime pressure in 1933. With a name that means “house of building” and a founding manifesto that declared its goal to be “the unified work of art,” the school taught both applied and fine arts around the concept to “not just create objects but recreate the notion of modern living,” Barry Bergdoll, an art history professor at Columbia University, said at the gathering.

There was no such thing as Bauhaus style; the school welcomed experimentation and collaboration, and honored a “purposeful diversity,” according to Leah Dickerman, the director of editorial and content strategy for the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. “The legacy of the Bauhaus became even more important after the Bauhaus closed, because an ethos and way of thinking carried on.”

There was no such thing as Bauhaus style; the school welcomed experimentation and collaboration, and honored a “purposeful diversity,” according to Leah Dickerman, the director of editorial and content strategy for the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. “The legacy of the Bauhaus became even more important after the Bauhaus closed, because an ethos and way of thinking carried on.”

Rather than submit to Nazis terms, the school closed and a diaspora began. Bauhaus founder and first director Walter Gropius settled in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to teach at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. Besides influencing hundreds of students, his architectural legacy includes dozens of buildings in the United States. And the school itself experienced a new life in this country—thanks to Walter Paepcke, the head of the Container Corporation of America and the Institute’s founder. With the funding and support of Paepcke, the Hungarian multidisciplinary artist and Bauhaus master László Moholy-Nagy came to Chicago to lead the New Bauhaus school. The artist, whose influence in applied crafts is richly documented in Jazzar’s Doerr-Hosier exhibition, remained in Chicago, working and teaching until his death, in 1946.

Bayer had worked with both Gropius and Moholy-Nagy at the Bauhaus, which he joined as a student in 1921. He left the school as a master in 1928, to gain more work experience and pursue ambitions in Berlin as a graphic designer. By then, Bayer had embraced the Bauhaus idea of collaborating with industry to help shape daily life. As he built his practice and career, it became clear that Hitler’s ambitions and hostility to modern art would disrupt his life and work. Bayer followed Gropius and others to the United States in 1938. His first project was designing a Bauhaus exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art.

Like the Bauhaus in its short life, Bayer transformed and re-branded himself multiple times. By the time he landed in New York, he had done significant work in collage, watercolor, sculpture, painting, typography, advertising and marketing design, and exhibition design. Even if he considered himself apolitical, three of his paintings were included in the Nazi-sponsored Degenerate Art exhibition in 1937. His ambition drove his work—and led him to do advertising and design work from 1933 through 1937 that could be considered propaganda for the Third Reich.

That work continues to make Bayer’s legacy problematic. Speakers referred to Bayer’s Americanborn Jewish wife, Irene Hecht, whom he married in 1925 and separated from in 1928, after they had a daughter, Julia, Jewish by birth. Elizabeth Otto, an art and cultural historian at the University at Buffalo College of Arts and Sciences, expressed one opinion in the art history community by telling the group that she had been deeply upset on discovering Bayer’s propaganda work to benefit the Nazis but that she also questioned the validity of judging another’s decisions without knowing the full context of the decision.

Robert Wiesenberger, associate curator of contemporary projects at the Clark Art Institute, expressed another. Bayer’s careerism, he told the group, was “substantial and sustained complicity with fascism.” Similar to the ways we choose today to respond to the evidence and threat of climate change, Wiesenberger said, Bayer “knew everything he needed to at the time. One always has a choice.”

Bayer would transform himself again—and play a major role in transforming a whole town—when he came to Aspen in 1946 in the employ of Paepcke; Bayer designed advertisements for Paepcke’s Container Corporation. Paepcke intended to attract tourists to the former mining town and nascent resort, and Bayer’s promotional materials—ski posters, the now-ubiquitousaspen-leaf logo—helped the ambitious project succeed. Bayer had grown up in Austria and was by birthright a good skier, and he found happiness in the mountains—a contentment, Jazzar said, evoked in the soft lines and peaceful moods of his “underappreciated” mountain paintings from that era.

Along with restoring some of Aspen’s best Victorian architecture and designing new structures in the simple, modern style by now associated with the Bauhaus, Bayer took on the master planning of the Aspen Institute campus—a 20-year endeavor that fulfilled his Bauhaus-fueled hopes to tackle “the design problems of our time.”

His first structure was the seminar building, now the Koch Building, completed in 1953. Bayer incorporated into the building a sgraffito mural, a technique he had learned from Wassily Kandinsky at the Bauhaus, whose lines mirror the contours of nearby Red Mountain. He and his team worked at night, using powerful lights to guide their way, in an effort to avoid the bright sun drying out the plaster too quickly.

His first structure was the seminar building, now the Koch Building, completed in 1953. Bayer incorporated into the building a sgraffito mural, a technique he had learned from Wassily Kandinsky at the Bauhaus, whose lines mirror the contours of nearby Red Mountain. He and his team worked at night, using powerful lights to guide their way, in an effort to avoid the bright sun drying out the plaster too quickly.

Then came the Grass Mound in 1955, the first earthwork structure in the United States and the beginning of a trend in earthwork as art—a trend that in the 1960s took on international significance and one its chief proponent, Michael Heizer, attributed to Bayer’s innovation, according to Jazzar.

The Health Center, completed the same year, features a flat roof for sunbathing, a spiral staircase, and a colorful mural, all elements that remain iconic. It anchored the west side of the campus, which was devoted to lodging, recreation, and relaxation as well as the notion ingrained in the Aspen Idea that to be a complete person, one must not only nurture the mind but also the body and spirit.

After Paepcke died suddenly, in 1960, Bayer was asked to create a new building in his memory. The resulting Paepcke Memorial Building, still the focal point of the east side of campus, “is one of the most amazing structures Bayer designed,” Jazzar said. “You can’t call it Bauhaus architecture; it’s Herbert Bayer architecture.”

Echoing Bayer and Paepcke’s founding idea that the Institute should reflect democratic engagement, the Paepcke Building houses meeting spaces and offices; its centerpiece is the auditorium, with its cleverly concealed tall, narrow windows to let in light and views. On one side, a hexagonal courtyard links the Paepcke building with the seminar building and its own hexagon-shaped meeting rooms.

Echoing Bayer and Paepcke’s founding idea that the Institute should reflect democratic engagement, the Paepcke Building houses meeting spaces and offices; its centerpiece is the auditorium, with its cleverly concealed tall, narrow windows to let in light and views. On one side, a hexagonal courtyard links the Paepcke building with the seminar building and its own hexagon-shaped meeting rooms.

Besides creating “beautiful geometries,” according to Jazzar, Bayer’s brilliance in design was to fit in new structures with existing ones and with the landscape—as well as how timelessly the design would complement its function. The modest size and low profile were signature Bayer design principles—in scale with human beings and in relation to the mountains that spectacularly surround the campus. Bayer’s use of hexagons and octagons, over and over again, to facilitate egalitarian meetings in the round reflect the founding ideals of the Institute that Edmund de Waal evoked at the gathering: to bring leaders and thinkers together in a neutral, contemplative place to exchange ideas and grapple with the human issues of the time.

His last masterpiece involved design and building, but not bricks and mortar. In the early 1970s, Robert Anderson, then-president of the Institute, asked Bayer to fill in the space between two sides of campus. Bayer’s response was Anderson Park, “a masterpiece of earthwork sculpture,” Jazzar told the group, that “we all walk through every day.”

With its mounds, terrain undulations, and ponds, Anderson Park, completed in 1973, achieves the balance Bayer sought between the man-made structures on campus and the landscape beyond. It also serves as a mental transition: Bayer wanted people to walk from their cars to the buildings and in between the buildings, to invite reflective thinking. Many campus visitors, Jazzar said, “don’t even realize they’re walking through an art piece, because it looks as natural as possible. It’s a magical space that has come to represent the ideal of the Aspen Institute.”

“Herbert Bayer designed every part of this campus,” Jazzar told the Society of Fellows gathering. “Every aspect you experience [on campus] is because this man thought of everything, from the siting of the buildings to air circulation to the way water flows through the space. It’s why it’s the total work of art. The Institute campus truly reflects Bauhaus ideals as interpreted by Herbert Bayer and manifested in this amazing location.”