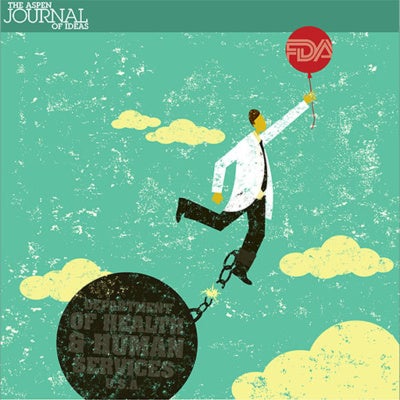

When six former commissioners of the Food and Drug Administration declared from the stage of Spotlight Health 2016 that the FDA should become an independent federal agency, the Institute’s Health, Medicine and Society Program staff knew immediately that news was being made. And sure enough, the announcement was widely publicized, with stories appearing in Fortune, Politico, STAT, industry trade magazines, and elsewhere.

When six former commissioners of the Food and Drug Administration declared from the stage of Spotlight Health 2016 that the FDA should become an independent federal agency, the Institute’s Health, Medicine and Society Program staff knew immediately that news was being made. And sure enough, the announcement was widely publicized, with stories appearing in Fortune, Politico, STAT, industry trade magazines, and elsewhere.

What none of the media quite realized was that this consensus had emerged only during the commissioners’ informal conversations a few minutes earlier. Although they represented both sides of the political aisle, each of the commissioners had privately reached the same conclusion, based on their own experiences at the FDA. But it was far from a fully fleshed-out idea. No one really knew what an independent agency might be like. What would it take to pull the FDA out of the US Department of Health and Human Services? Who would approve its budget, and what kind of leadership would it have? How would it be held accountable? Did other models of independence within the federal government offer any guidelines?

Representatives of the Laura and John Arnold Foundation were in the crowded auditorium of the Doerr-Hosier Center as the commissioners spoke, and they quickly expressed interest in getting some answers. Soon after, they funded the Health, Medicine and Society Program to help the commissioners put meat on the bones of their idea.

Over the next year, the Health, Medicine and Society team interviewed each of the commissioners to learn more about their thinking, and we also sought ideas from other experts representing the views of industry, consumers, regulators, and others. We combed the research literature and documented the many challenges the FDA faces in a world of rapidly evolving science.

Our investigation highlighted huge increases in workload—in 2016, the agency issued nearly 450 rules and guidance documents, compared with a little more than 100 a decade earlier, and the volume of imports subject to regulation increased by 250 percent. We learned that senior FDA staffers thought it should take less than two years to finalize a new rule, when it actually takes more than seven. We also built a model showing that avoidable delays in publishing regulations were costing the public billions of dollars, and we constructed a flow chart illustrating the convoluted steps needed to move a proposed rule into its final form.

Two in-person meetings allowed the commissioners to review the evidence, engage in vigorous discussions, and decide how best to go public with the case for independence. Although they agreed on the overall goal from the start, reaching consensus on the language and framing of their recommendations was a delicate process. Word choices can be very significant in a political context, even if the distinctions sometimes elude the layperson. Does the FDA promote and protect public health? Or protect and promote it? Will a potential ally be annoyed if the HHS review process is labeled exceptionally unwieldy? What should be said about the risks of political interference, especially on a powder-keg issue like abortion?

The program team supported the commissioners—now seven, after the most recent left his post and joined his colleagues—as they navigated their differing perspectives. In the end, they all agreed to co-author a short commentary for publication in Health Affairs, the nation’s most prestigious health policy journal. That article outlines the principles behind their call for independence, offers a pathway to get there, and links to a more detailed report on the Health, Medicine and Society website that provides further context and supports the arguments with data and charts.

The commissioners’ foundational belief is that reengineering the FDA will ensure that essential health and safety regulations are firmly rooted in the latest science and will keep the agency at the epicenter of developing new products and technologies that benefit the American public. The core insight is that meeting the FDA’s responsibility for more than $2.4 trillion in products—19,000 prescription drugs, 85,000 tobacco products, 75 percent of the nation’s food supply, as well as cosmetics, veterinary products, blood-related products, and much more—requires a streamlined decision-making process. The recommendations emphasize that a restructured FDA would still be subject to oversight but free from administrative bottlenecks, putting it in the strongest possible position to meet the challenges of the 21st century.

After two years of effort, it is fair to ask one candid question: will all that hard work really lead to FDA independence? In the immediate future, the answer is most likely no, given the lengthy negotiations and federal legislation required to move the FDA out of the Department of Health and Human Services. But the commissioners also proposed interim steps that would enable the FDA to operate more efficiently under its current structure. As significant, all seven are on record as favoring independence, allowing bipartisan debate to keep moving forward. It is a landmark recommendation, and it all started one summer on the Spotlight Health stage.