His voice rising and falling with dramatic effect, historian Roger McGrath told the story of the 1848 discovery of gold in California in sharp detail. From the chill of that January morning in the Sierra Nevada foothills at Sutter’s Mill, when a mill employee noticed a glint that turned out to be gold nuggets, to the ensuing rush that made some men rich and flooded California with American settlers, McGrath’s listeners relived history.

His voice rising and falling with dramatic effect, historian Roger McGrath told the story of the 1848 discovery of gold in California in sharp detail. From the chill of that January morning in the Sierra Nevada foothills at Sutter’s Mill, when a mill employee noticed a glint that turned out to be gold nuggets, to the ensuing rush that made some men rich and flooded California with American settlers, McGrath’s listeners relived history.

That discovery at Sutter’s Mill ushered in “50 years of grand adventure in the wildest, woolliest phase of the American frontier,” McGrath said. The American West was the theme of the Society of Fellows’ second annual summer symposium, a three-day program held at the Institute’s Aspen campus. Panel discussions and presentations by two dozen academics, historians, writers, and other experts let participants explore the West’s history as well as its villains and heroes, myths and realities, values and vices, and legacy and lessons.

“The imagined West is such a dominant component of the American national character,” Ned Blackhawk, a Western Shoshone and a Yale history professor, said at the opening discussion. “Some scholars say it is the most imagined region of the American landscape. And that’s affected us. Frames help us imagine a landscape.”

“The imagined West is such a dominant component of the American national character,” Ned Blackhawk, a Western Shoshone and a Yale history professor, said at the opening discussion. “Some scholars say it is the most imagined region of the American landscape. And that’s affected us. Frames help us imagine a landscape.”

The myths of the 19th-century American West—cowboys versus Indians, black-hatted outlaws versus white-hatted lawmen—became stubbornly entrenched in popular culture with the pulp novels of the day, called “blood and thunders,” and spread worldwide (especially in Europe) through the works of best-selling German author Karl May and, later, Hollywood. But the reality is more complicated.

“A big part of the story of the American West is that it’s where reality and myth collided—sometimes gently, sometimes head on,” Michael Wallis, the author of 19 books and hundreds of articles on the American West, told the group. “There were some white hats and some black hats—but there were many, many gray hats, and some of those were dark gray.”

Native Americans, in particular, have seen their stories simplified and flattened. The program explored the cultures and values of the numerous tribes that had inhabited the region some 10,000 years before the arrival of Europeans—busting the myth of an empty landscape—as well as their struggle to survive during the American westward expansion. The attention to that culture brought forth a much more nuanced history than most have learned.

Author Hampton Sides uncovered plenty of nuances while researching his epic history of the American West, Blood and Thunder, told largely through the life stories of In some ways, today’s stark divides mirror the Wild West: westward expansion, long considered the project that made the United States a great power, involved conflicting stories, antiheroes, and many lives lost.

American frontiersman Kit Carson and Navajo chief Narbona. The Navajos, for example, were a semi-nomadic agricultural tribe that adopted the use of sheep and horses from Spanish settlers and were best known for their intricate rugs and textiles. During a public lecture as part of the Society of Fellows program, Sides called the Navajo “the most American of American Indians because of their unique talent for ushering new ideas and new concepts wherever they roamed across the Southwest.”

Kit Carson, a central character of early blood and thunders, epitomized the clash of myth and reality, conflicting values, and how manifest destiny was shaping the American West. According to Sides, Carson was happiest during his years as a mountain man, married to an Arapaho woman and living among the tribe. Later, as a guide for and member of the US Army, he played a key role in opening the West to American settlement and “participated in the destruction of the world he loved,” Sides said, fighting and killing Indians. To some, Carson became a “wonderful folk hero,” while to others, he was “a genocidal maniac.” The truth, Sides noted, was somewhere in the middle.

Why the 19th-century West matters today was the theme of the final day of the conference. American ideals of self-reliance, individuality, and direct democracy strengthened in that era and found their way into politics and policies that continue even now. In some ways, today’s stark divides mirror the Wild West: expansion into the American West, long considered the project that made the United States a great power, has since proved to include conflicting stories, antiheroes, and many lives lost.

The challenge now becomes, according to the director of the Center for the Southwest, Virginia Scharff, “How do we tell stories about our common past when we come to our past from so many different places?”

Perhaps one answer is gatherings like the American West program, which allowed attendees to explore the stories and values that shaped US history in “a shared experience that’s fun and engaging,” Peter Waanders, the director of the Society of Fellows, says. “Getting people together to talk about ethical decision-making in the 19th century gives them a chance to step outside of today’s debates along political divides and to see both sides of an issue and perhaps find common ground.”

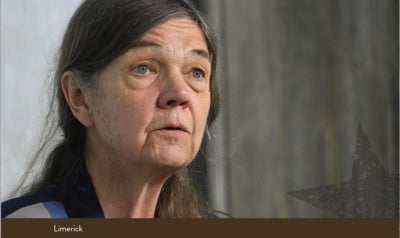

Or even more simply, as American West historian and professor Patty Limerick put it, “Rather than say, ‘Let’s do some fact checking,’ can we invite people into the conversation and say the story is more interesting if you put the complexity into it?”

Or even more simply, as American West historian and professor Patty Limerick put it, “Rather than say, ‘Let’s do some fact checking,’ can we invite people into the conversation and say the story is more interesting if you put the complexity into it?”