This post is the first in a series reflecting on the 2018 Economic Security Summit. To follow this series, visit the Aspen Institute’s Reconnecting Work and Wealth page.

In July, a talented and diverse group from academia, business, worker organizations, foundations, and NGOs gathered at the third Aspen Institute Economic Security Summit to discuss how to reconnect work and wealth. The group was challenged to develop a “plan of action” that built on discussion of these issues at two previous Summits. This year’s group was well-equipped for its charge; it was richly populated with leaders on the front lines of inventing and implementing innovative strategies for transforming our economy and society to be more inclusive and secure for all.

Let’s see if you think we lived up to our billing. If so, we encourage you to join us in one or more of the proposed actions to get our country back on track.

The problem: Workers feel they don’t have a voice

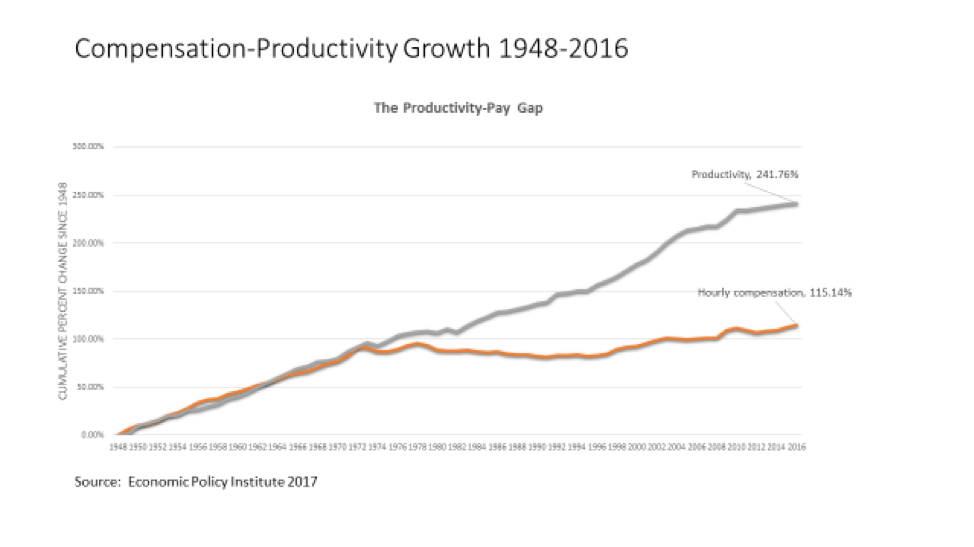

The post-World War II social contract supported the tandem upward movement of productivity and compensation from the 1940s through much of the 1970s. But as the first chart below shows, it broke down in the 1980s and it hasn’t recovered. Since 1980, productivity continued to grow while wages stagnated.

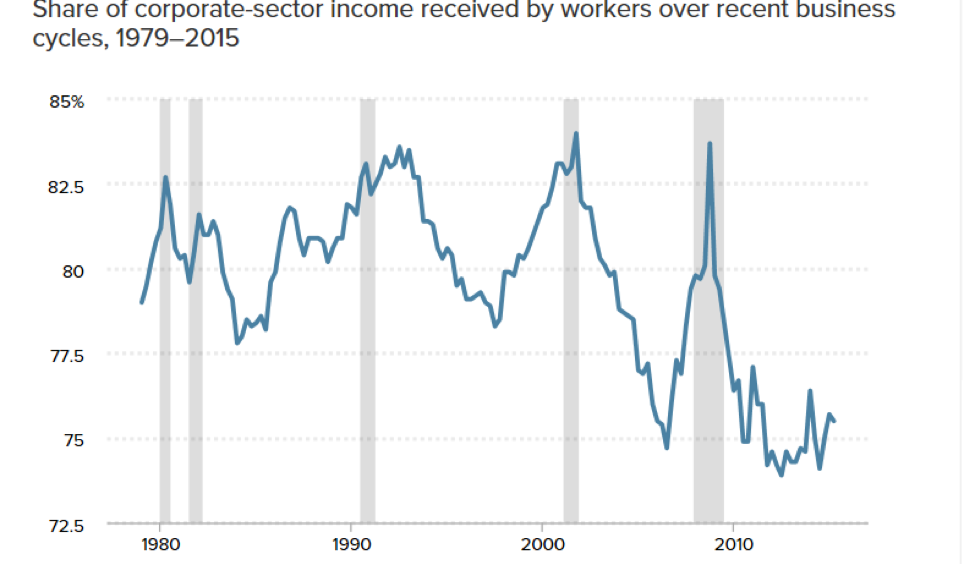

One of the consequences of this is that labor’s share of corporate income declined from 82 percent to 75 percent between 1980 and 2014.

Source: Economic Policy Institute

Source: Economic Policy Institute

At the Summit, I joined a group focused on addressing these issues by updating and supporting the development of new institutions, policies, and platforms that will strengthen the voices of all workers and enhance their economic security.

Rebuilding institutions for worker voice

From the group focused on institutions, there were two areas that I see as crucial to making a difference: building and repairing models to support worker voice and educating financial institutions about the value of good jobs for business.

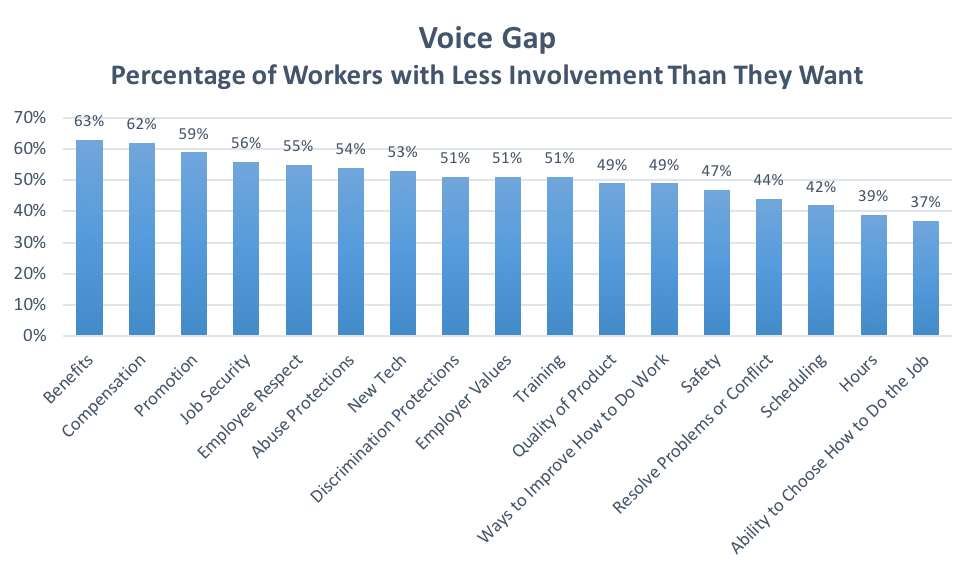

The need for rebuilding institutions is clear in the data from a 2017 national survey on worker voice by the Good Companies, Good Jobs Initiative at MIT Sloan. A majority of American workers report having less of a voice at work than they believe they should have on benefits, wages, promotions, job security, respect, and training. And more than a third to half of respondents report experiencing a voice gap on other workplace issues.

Source: MIT 2017 Worker Voice Project

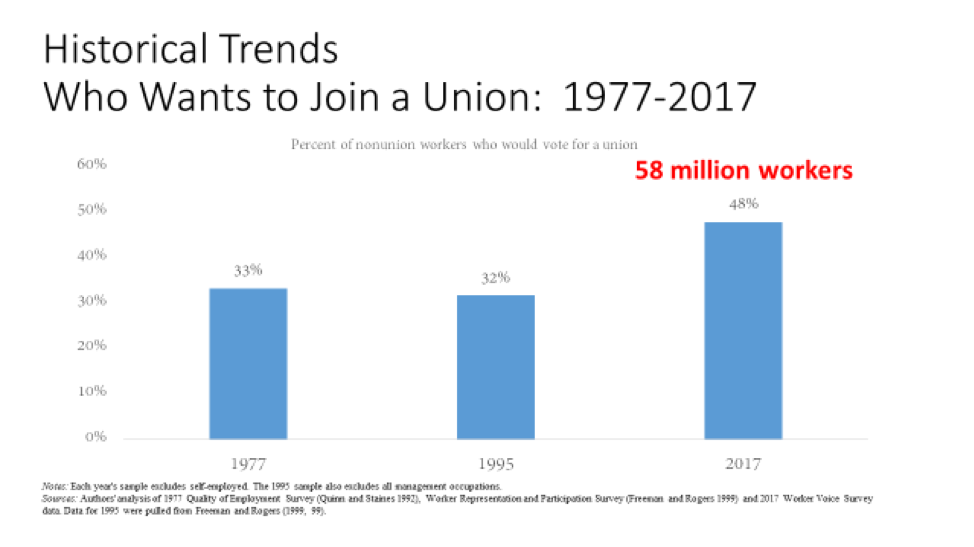

What’s more, the survey found that nearly 50 percent of nonunion workers today would join a union if given the opportunity to do so at their workplace, a rate of support that has increased from about one third of the nonunion workforce since the 1990s.

Source: MIT 2017 Worker Voice Project

At the core of this issue is a debate over what types of organizations can best achieve the power, scale, and sustainable revenue models needed to fill these voice gaps. To some, the current labor movement is incapable of reversing its half century of decline. Others believe that unions are open to innovations and new models of organizing that can lead them back to prominence.

In the midst of this, a growing number of emerging worker advocacy groups are showing promise. But none have yet achieved a large scale, and few have clear strategies for producing the power or revenue needed to be sustainable. Continued experimentation, collaboration, evaluation, and broader dissemination of lessons learned will help lead us to solutions to the challenge of bolstering worker voice.

While experimentation is needed, ultimately, supporting and sustaining efforts to rebuild worker voice will require a fundamental change in labor law. The current legal framework is so flawed that most of the emerging models of worker advocacy are careful not to get defined as labor organizations so as to avoid being covered by and therefore shackled by existing labor law. We need to develop new approaches to labor law and related policies to close the voice and representation gaps for workers currently excluded from legal protections.

Beyond worker voice, we also need more financial institutions to support entrepreneurs who are committed to building a good jobs strategy into their business models and plans right from the start. Venture capitalists and other capital providers too often reject business plans that provide for a significant number of standard employees (as opposed to relying heavily on independent contractors). To change this, we need more convincing evidence that companies that create and support good quality jobs achieve financial returns at least as good as those that rely on temporary and contract workers. This in turn requires better data capable of measuring the quality of employment practices in organizations seeking funds from investors.

What’s next: moving from conversation to action

Many of us have been to meetings that discuss ideas like the ones summarized here. But what set this meeting apart is that concrete and specific commitments were made to follow up on the ideas generated. For example:

- Our group at MIT Sloan will continue to study options for rebuilding worker voice and will host a network-building workshop for those on the front lines of innovations within the labor movement, those working in coalitions of labor and community or NGO groups, and those working independently. This will be the first time these groups are brought together to share experiences and explore ways that they work as complements to each other rather than competitors.

- The Center for Labor and Work Life at Harvard will bring together leading labor policy experts to take a “clean sheet” approach to developing a new labor law.

- On the financial front, there are already efforts underway at Just Capital, the Aspen Institute, B-Lab, and others to develop the measures needed to educate investors.

The goals we set forth and the next steps that we pledged at the Summit are just part of a broader effort needed to reconnect work and wealth. I’m hopeful that this great discussion will keep this era of experimentation and learning going and encourage others to join us in inventing, supporting, and growing the innovations needed to achieve a more secure future for all.

Thomas A. Kochan is the George M. Bunker Professor at the MIT Sloan School of Management and a Faculty Director of the Good Companies, Good Jobs Initiative at MIT Sloan.

The views and opinions of the author are his own and do not necessarily reflect the view of The Aspen Institute Economic Opportunities Program or Financial Security Program or its funders.

Share now

Tweet How do we strengthen workers’ voices? @TomKochan of @MITSloan reflects on this year’s Economic Security Summit and the institutional reform needed to create more inclusive and secure economy.

Tweet Wages have stagnated since 1980 – what institutions, platforms, and policies can change this trend? @TomKochan of @MITSloan shares the approaches suggested at July’s Economic Security Summit.

Tweet .@MITSloan’s @TomKochan reflects on the 2018 Economic Security Summit and how we can best reform institutions, policies, and platforms that will strengthen workers’ voices and enhance economic security.

Tweet Nearly 50 percent of nonunion workers would join a union if they could. How do we build organizations that meet workers’ needs in the modern economy? @TomKochan of @MITSloan reflects on solutions proposed at the Economic Security Summit.