(Photo Credit: istockphoto)

This article originally appeared at The Atlantic.

A specter is haunting America—not the specter of socialism or fascism, though both are certainly lurking, but the specter of bigness.

Big, concentrated power defines the lives of so many Americans today. That’s easy to overlook amid the celebration of disruptive technologies that flatten hierarchies, or social media platforms that allow the unsung to sing. But in sector after sector, from finance to media to food production, a shrinking number of winners is taking an expanding share of the gains—and has been, for decades.

This reality is fueling the candidacies of both Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders. For while the one likes to boast how “YUGE” he is and the other is unabashed about praising big government, what both have truly tapped into is a popular vein of anti-bigness: the sense among tens of millions of citizens that they’re too small to matter.

The leaders who not only hear this anger but also address its true causes will shape the next several decades of American civic life.

First, a little context. There’s always been economic inequality in America. But in earlier times, at least for the white men who dominated public life, there existed compensating forms of civic authority. There were clubs and associations where a laborer or a clerk could be in charge and could earn esteem. It was possible to be a nobody at the workplace and a somebody in the square; to experience rough civic equality even if material circumstances were highly unequal.

Today, much of that Tocquevillian ecology—which lasted well into the mid-20th century—has withered away. What remains, as sociologist Robert Sampson shows in his research on “neighborhood effects,” underscores the concentration of wealth and social capital that caused the withering.

The leaders who hear this anger and address its true causes will shape the next several decades of American civic life.

Consider how much PTAs do for affluent public schools in your town and how little they do for impoverished ones. Consider how few low-wage workers become officeholders or organizational leaders. There are fewer places in America now to assert a claim of civic dignity that can counter the experience of economic indignity.

Trump and Sanders have successfully exploited the resulting resentment. But neither of them—indeed, no candidate in either party—has tailored a sophisticated agenda in response to it. Fortunately, we have a useful precedent. A century ago, at the dawn of another Gilded Age of pernicious bigness, Louis Brandeis laid out a solution to self-perpetuating concentrations of power: a politics against monopoly.

Brandeis, a pioneering legal activist who served on the Supreme Court from 1916 to 1939, recognized that while many capitalists praise competition, what they want really is monopoly—and that true competition, in which more people get more of a chance to challenge entrenched winners, should be the object of public policy.

True competition—now, as then—requires recognition that economies and communities are not static mechanisms. They are complex adaptive systems, in which both advantage and disadvantage compound. It’s not just that the rich get richer and the poor poorer; it’s that the rich get louder and poor quieter.

This amalgamation of market power, political voice, and social mobility is the natural outcome of a system left to itself—of laissez-faire ideology. True competition demands an economic and civic program of actively busting “opportunity monopolies” and recycling the unearned privilege that comes with them.

Brandeis articulated such a program and put elements of it into place both as a “people’s lawyer” and as a jurist. What would a 21st-century agenda look like? It would focus on anticompetitive acts not only in the economy but also in the polity.

There are elements that much of today’s left would like: A much more robust inheritance tax. A progressive funding source for public schools delinked from property values. Higher wages for the working poor, and easier ways for workers to organize and bargain. Democracy vouchers, like the public campaign-finance system just enacted in Seattle to give everyday voters more power to be donors. Capital requirements for banks and a “size tax” for financial institutions. Antitrust enforcement that promotes competition and not just efficiency.

There are also elements many on the right would favor: Unwinding corporate subsidies and cronyism on Wall Street and in government contracting. A radical simplification of the tax code so that tax breaks no longer flow overwhelmingly to affluent families. Changes to union contracts that make it easier to replace poor performers. Limits on the scale of government agencies so that they don’t become “too big to serve.”

Then there are elements that could scramble ideological expectations: Killing the alumni preference in college admissions and creating a poverty preference. A guaranteed basic income. Baby bonuses. A draft—for women and men alike, for armed or civilian service. An expansion of jury duty to other forms of participation—on local commissions, say. A longer freeze of the revolving door from government to the private sector. A radical push of responsibility—with real funding attached—to what Brandeis called “laboratories of democracy” in states and cities.

Every public policy should be put to a simple test in a politics aimed against monopoly: Does it enable insiders to hoard opportunity? Does it reward the already privileged and entrenched for being privileged and entrenched? If so, it must be changed. The resulting agenda doesn’t line up neatly with either party platform. It does line up with the most passionate parts of the contemporary electorate, right and left.

It’s not clear if any of the remaining presidential contenders will be able to make this case for busting opportunity monopolies, or to turn anti-hoarding ideas into legislation, or to set it all in a compelling moral and narrative frame. But to channel the spirit of Brandeis, it doesn’t take a president—it takes a citizen. This is a story all Americans should all start spreading, and practicing, in the laboratories of their civic lives.

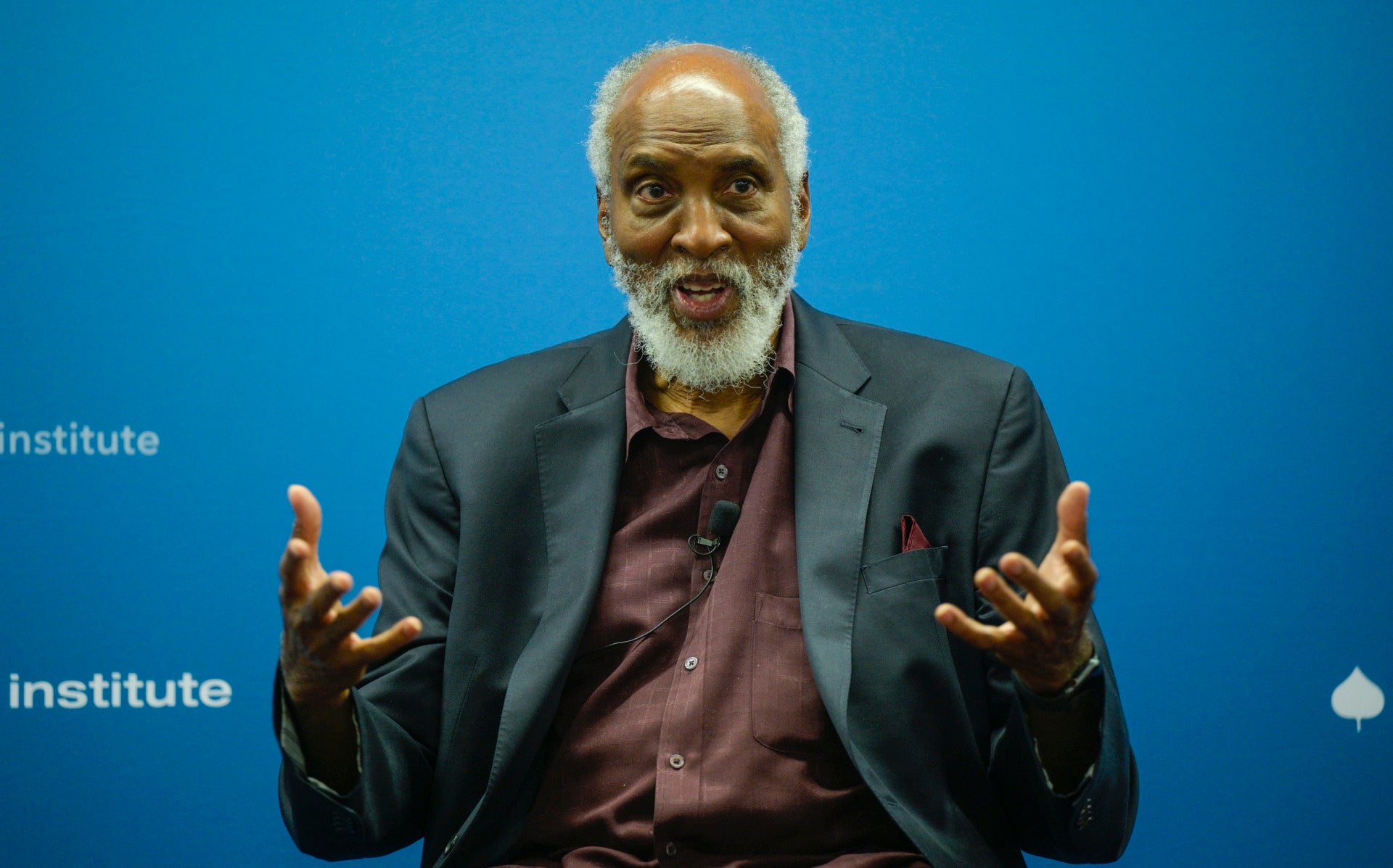

Eric Liu is a contributing writer for The Atlantic. He is the author of A Chinaman’s Chance, co-author of The Gardens of Democracy. He is founder of Citizen University and executive director of the Aspen Institute Program on Citizenship and American Identity.