On a recent Sunday afternoon, a dear friend commented that it is a fascinating time to study how much our society values lives, as implied by policy decisions to contain COVID-19 and re-open economies. How much decreased economic activity is our society willing to accept to extend a person’s life? How much prosperity are we willing to give up? How much increased poverty, malnutrition, and homelessness will we tolerate?

As it had been months since my friend and I last caught up, our conversation turned to more humorous and personal topics and I didn’t think about the bigger questions for the rest of the evening. But my friend’s comment seeded unconscious explorations during sleep, as did a public Aspen Institute Connected Learning Seminar in which I had participated three days prior.

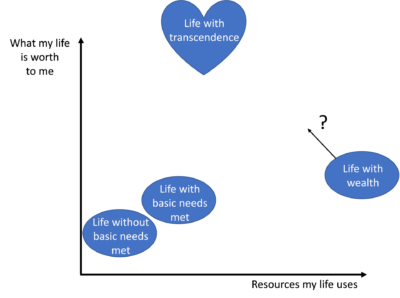

The following morning, I woke up wondering about the relationship between a life’s worth and the economic resources that it uses. I started by reflecting on my own life.

Three concepts arose: basic needs, wealth, and transcendence. Basic needs relate to physiological needs, such as safety, clean water, food, and shelter. Wealth relates to material possessions and purchasing power. Transcendence, at this point in my life, relates to the answers to the questions:

- Do I feel purpose?

- If I died tomorrow, would I feel at peace, and that I had lived life well?

- Is my positive life experience contingent on things that I might lose, or does it come from within?

It strikes me that the life that I most value, one with transcendence, does not require the most resources. While I feel comfortable with that idea in general, part of me feels uneasy attributing different values to different paths my life could take based on my access, privilege, and life choices. Aren’t all lives (and possible paths of the same life) worth the same? But I do value the emotions evoked from seeking transcendence more highly than those that result from seeking material possessions or social status.

Upon further reflection, I also feel uneasy valuing a version of my life with wealth more highly than one with lesser wealth, or depicting one with more transcendence as taking a bit more economic resources than one with basic physiological needs met. Wouldn’t a Buddhist monk or most other spiritual leaders or psychologists teach that transcendence is not about seeking material possessions? But I have not yet achieved such levels of enlightenment and I do place value on some things beyond physiological needs that provide comfort, knowledge, connection, or experiences. For me, these are all dueling tensions.

The diagram also evokes in me questions about broader implications. I wonder whether a society focused on building wealth could eventually shift to building transcendence. If so, would it already have more than enough economic resources to do so? Would people be better off as a result? And how would people come together to decide on their goals and approaches?

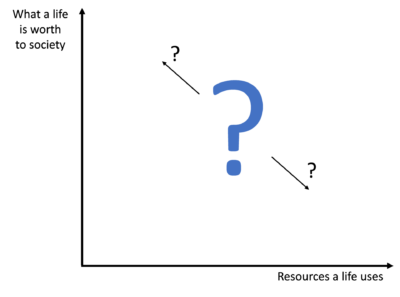

In light of current efforts to contain COVID-19 and re-open economies, I also wonder how much a life is worth to society, but I don’t yet have the wisdom nor the courage to begin to answer that question.

But aren’t we, as a society, implicitly answering that question every day? Cost per death averted, for example, informs public policy decisions, including those concerning containment of COVID-19. We also make assumptions about a life’s worth in everyday judicial rulings and insurance policy pricings. Doing so seems logical, but couldn’t we benefit from examining our logic and customs more closely and transparently?

For example, are we comfortable with our present practices of valuing lives in developed economies more highly than those in emerging ones? Or valuing working people more highly than those taking care of children? Do different lives have different degrees of worth to society? Considering such question evokes in me strong ethical dilemmas and feelings of my own unworthiness. But was the life of Adolf Hitler worth the same as that of Marie Curie? I don’t think so. So what else might be relevant? Is the life of a successful entrepreneur, who creates many jobs, worth more or less than that of a spiritual leader, who helps many people grow spiritually? Is the life of a baby, who can be expected to live several decades, worth more or less than that of an elder who has valuable wisdom to share?

We may choose to turn away from these questions to avoid discomfort, but as a society we regularly make decisions that imply answers. Are we comfortable with letting inertia drive those answers? If we don’t wrestle with the questions, they will not be answered as thoughtfully, inclusively, and transparently as we would want. Only by taking risks and grappling can we grow.

How much is a life worth? I don’t know, but I think I know a little more than I did yesterday.

The views and opinions of the author are his own and do not necessarily reflect the view of The Aspen Institute or the Aspen Executive Leadership Seminars Department.

Eduardo Briceño is the Co-Founder & CEO of Mindset Works.