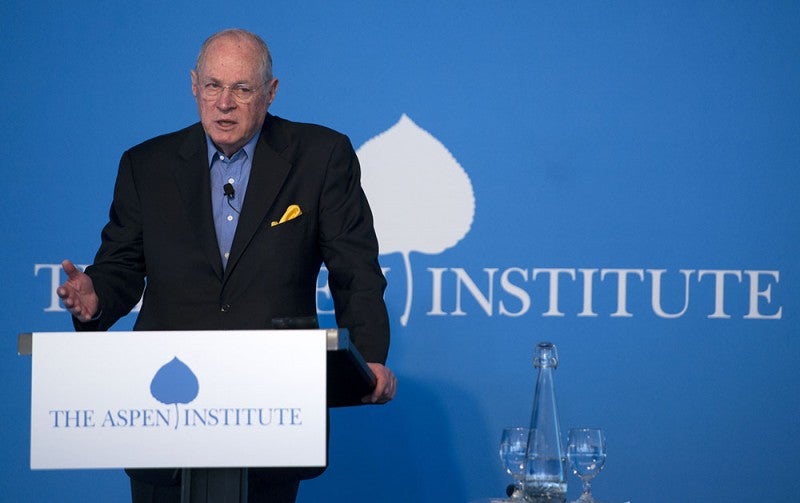

US Supreme Court Associate Justice Anthony Kennedy at the Aspen Institute in Aspen, CO.

The US Constitution is an imperfect document, and democracy is a work in progress, US Supreme Court Associate Justice Anthony Kennedy told an Aspen, Colorado, audience recently at a public forum hosted by the Aspen Institute Justice and Society Program. And it’s up to the people to carry forward the aspirations of the United States’ founding document and the freedoms and responsibilities of the society it supports.

With the 800th anniversary of the Magna Carta approaching in 2015, Kennedy discussed the seminal British legal document’s history, its influence on American legal doctrine and the Constitution, and its continued significance today.

Signed in 1215, the Magna Carta was “a scattershot list of provisions,” Kennedy said. But it built on an idea of personal freedom and legal rights that were first codified in William the Conqueror’s “Domesday Book” of 1086, which listed all property in the realm for purposes of taxation. The effect was quite the opposite, noted Kennedy:

“It was an affirmation that you owned legal property and you had a right to that property. And from this idea that you have the right to keep the king off your property came the further idea that you have personal autonomy, dignity, a self definition that the state might not co-opt for itself.”

The Magna Carta contains clauses that are the seeds of foundational American legal tenets, such as no taxation without representation, no excessive fines, and just compensation, Kennedy explained. But chapters 39 and 40 are “the far-reaching, expansive ones… from which we discover greater, more enduring principles.” Chapter 39 is the basis of the concept of jury trial, and Chapter 40 is about swift justice. But both of those provisions imply greater meaning, he said: “It is the people telling the king what the law is that puts the Magna Carta in a class by itself. Like the first three words of the Constitution: ‘We the People.’ We tell the government what the law is.”

William Penn brought the Magna Carta to the American colonies, where its principles were used in some early states’ charters, said Kennedy. Then came the Constitutional Convention, during the hot summer of 1787, when George Washington kept the delegates in a stuffy room for three months until the document was refined and signed (the Bill of Rights was ratified three years later, in 1791).

Yet “of course the Constitution was imperfect,” said Kennedy, noting its allowance of slavery and the resulting Civil War, which left some 600,000 dead and led to the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments. Many elements of the original Bill of Rights were not tested by the courts until the 20th century.

“So democracy is still trying to achieve perfection,” he said.

Noting that Plato and Aristotle did not like democracy because they believed it was incapable of becoming mature, he turned his focus to current affairs in the United States:

“Do you have a mature democracy given the state of civil discourse and political discourse you have today? Does it set an example to the rest of the world? Does it show that democracy can mature when you have the political branches in such deadlock, the nation just adrift, and you don’t have the political will to have policies on immigration and spending?”

Kennedy emphasized the need to educate young people on the importance of civic responsibility, something he said that the Athenians understood well.

“You don’t believe in freedom because it’s in your DNA. You believe in it because it’s taught, because you understand it,” he said. Freedom, he continued, is not simply “a right,” it is also “a duty.”

He also touched on challenges to the rule of law today. As noted by Judge Diarmuid O’Scannlain, a member of the US Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals who introduced him, Kennedy’s definition of the term has been adopted by the United Nations. In a jovial tone that contrasted with a pointed remark, Kennedy said that the judicial branch is the only one of the three branches of US government that gives reasons for what it does, through written opinions, in part to command respect for its decisions.

He elaborated further on his point in response to a question from a participant in this summer’s Justice and Society Seminar, Lady Justice Mary Ang’awa of the High Court of Kenya, who queried Kennedy as to why American officials, in contrast to those in some African Union nations, execute the decisions of the Court, even when they disagree with them. The exchange illustrated that in many parts of the world the work of the judiciary is fraught with difficulty and danger, something Kennedy acknowledged.

Being the guardian of the Constitution, said Kennedy in closing, involves heavy responsibilities for the people. Contrary to the opinions of constitutional purists, Kennedy argued that the Constitution is a living document that by its very nature must be reinterpreted based on the conditions of the time.

“The Constitution has to have significance in your own time,” he said. “It doesn’t belong to a bunch of judges and lawyers — it’s yours!”

Catherine Lutz is a freelance writer based in Aspen, CO. Meryl Chertoff is the executive director of the Aspen Institute Justice and Society Program.