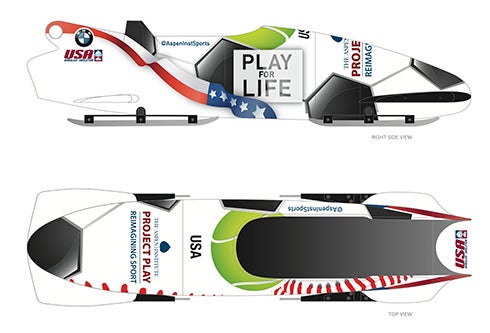

The USA Bobsled and Skeleton Federation has partnered with the Aspen Institute Sports and Society Program’s Project Play initiative to help stakeholders explore ways to get and keep children active through sports. Driven by Jazmine Fenlator, the Project Play sled will be unveiled on Saturday, Dec. 13, at the season-opening World Cup race in Lake Placid, New York. Below, the USA Bobsled Federation CEO Darrin Steele reflects on what he learned playing sports and the need to overcome today’s barriers to a positive experience.

I was working in one of my first real jobs after competing in the 1998 Olympics, and a colleague pulled me aside to ask some advice. He was frustrated with his 11-year-old son, who was a gifted youth soccer player. It seemed that the boy had lost his drive and his father was failing in his effort to get his son to work harder in practice. He wanted my help in convincing the boy to work harder. Without thinking much about it, I simply told him that the only thing he could do was to make sure the boy was having fun, because it shouldn’t feel like work at that age.

At the time, it seemed like a strange question. I didn’t have kids of my own, so all I had was my own experience as a youth athlete. I didn’t share the other thoughts that ran through my mind: If he was good at the sport, why wasn’t he having fun? If he wasn’t having fun, why was he still participating? How did it get to this point? My final comment to him was something I still believe today: “Once kids fall in love with a sport, get out of their way.”

I didn’t realize it then, but that conversation represented a disturbing trend in youth sports across America. I played every sport I could as a kid, both structured and unstructured. I remember the incredible feeling I got sprinting as fast as I could through the grass in my neighborhood without shoes or a stopwatch. I remember learning the Fosbury flop high jump technique for the first time and spending the next three hours practicing it with my brother because it was so much fun. We didn’t care that the height we were jumping was mediocre; we just raised the bar when we were ready for a bigger challenge. The same could be said for the first time I ran in the air in the long jump, bent the pole in the pole vault, or hit my first curveball. I wasn’t worried about being the best; I was just having fun and challenging myself. Becoming a professional athlete or Olympian some day was my fantasy, not my parents’ fantasy, and certainly not the actual plan. That came much later.

Now that I’m a parent, I understand the desire to give our kids the best possible opportunity to become successful adults. It’s ironic then, that the desire to protect our kids and help them succeed is too often having the opposite effect. Youth sports can provide incredible lessons for adulthood, but only if parents and coaches have some perspective. Most kids will not become professional athletes or Olympians, but the message is the same. Regardless of how far a person goes in sports, the athletic career will end and another career must start. That’s when the values that should be learned along the way will have their greatest impact.

My first lesson in “managing up” happened long before I began my first job in business. It was when my brother Dan came to my dad during his sophomore year in high school complaining that he was better than the starting wide receiver on our football team. My dad told him, “I think you’re right, you are better. But I’m not your coach. You need to find out why he doesn’t think you’re better and prove it to him.” And he did. The same could be said for learning to work in teams, overcoming adversity, strategic thinking, goal setting, leadership, and mental toughness. Youth sports have been more important to my post-‐athletic career than I ever would have imagined.

One of the most promising things about the future of youth sports and children in general comes from an unlikely source: video games. These are typically included as evidence of a growing sedentary lifestyle in our children that leads to obesity and diabetes. I won’t argue with that, but video games also contradict the narrative that today’s kids are dropping out of sports and avoiding physical activity because they are non-competitive, have a fear of failure, or are risk–averse. Most video games end the same way. The challenge increases until the player fails. The players must try different strategies, risking failure each time until they find one that works. The challenges increase gradually and the players are clear on what it takes to get to the next level. Most important, the financial success of every video game is dependent on the players having fun. It helps that they don’t have to worry about parents pressuring their kids to be the best at Grand Theft Auto or Candy Crush.

The video game industry is successful not because they are catering to changes in today’s children, but because they are giving kids the things that youth sports have largely stopped offering. There’s another important difference between video games and youth sports: the video game industry is selling to players. Youth sports and schools are selling to parents. The kids haven’t changed, we have.

There are still some great programs out there with coaches who get it. Some schools have even been bucking the trend in physical education with remarkable results. Right now, unfortunately, both examples are outliers. We have much to do if we are to change course, but the research overwhelmingly supports the benefits of doing so and the costs of doing nothing. Here are some facts to keep in mind:

- Kids who participate regularly in physical education in schools are less likely to be obese and more likely to participate in sports, yet regular P.E. is decreasing in our schools. (Toporek, 2013).

- The benefits of youth sports include character building, motor-skill development, healthier lifestyles in adulthood, team-building skills, goal-setting skills, confidence, and social skills (Hedstrom & Gould, 2004).

- Kids report that they play sports to have fun, do something they are good at, be with their friends, improve their athletic skills, and feel the excitement of competition (Hedstrom & Gould, 2004).

- Obese children are far more likely to become obese adults (Biro & Wien, 2010).

- Physical inactivity increases the likelihood of obesity, yet physical inactivity in children is on the rise (Ng & Popkin, 2012).

- Fitness stimulates brain development, improves the ability to focus (Sattelmair & Ratey, 2009), and increases grades and standardized test scores (Wittberg, Northrup, & Cottrell, 2012).

- School districts continue to cut PE programs and recess time, while ADHD diagnoses continue to rise (Boyle et al., 2011).

- Today’s 10-year-olds may be the first generation in history to live shorter lives than their parents (Olshansky et al., 2005).

- Annual costs for obesity-related medical expenses in the United States have increased from $78.5 billion in 1998 to $147 billion in 2008 (Finkelstein, Trogdon, Cohen, & Dietz, 2009).

- Top reasons kids stop playing sports include a lack of fun and parental pressure to perform (Sánchez-‐Miguel, Leo, Sánchez-‐Oliva, Amado, & García-‐Calvo, 2013).

It’s time to get back to the basics of why kids play sports so participation rates can expand. That’s why USA Bobsled & Skeleton is proud to support the Aspen Institute Project Play initiative and their efforts to do just that. It might not be realistic to go back to a simpler time in history, but we do have the ability to encourage, promote, and protect the things that make sports and fitness vitally important to our kids and our collective future. It won’t just happen. It’s time to act.

References

Biro, F. M., & Wien, M. (2010). Childhood obesity and adult morbidities. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 91(5), 1499S-1505S.

Boyle, C. A., Boulet, S., Schieve, L. A., Cohen, R. A., Blumberg, S. J., Yeargin-Allsopp, M., . . . Kogan, M. D. (2011). Trends in the prevalence of developmental disabilities in US children, 1997–2008. Pediatrics, 127(6), 1034-1042.

Finkelstein, E. A., Trogdon, J. G., Cohen, J. W., & Dietz, W. (2009). Annual medical spending attributable to obesity: payer-and service-specific estimates. Health affairs, 28(5), w822-w831.

Hedstrom, R., & Gould, D. (2004). Research in youth sports: Critical issues status (M. S. University, Trans.) (pp. 24). East Lansing, MI: Institute for the Study of Youth Sports.

Ng, S. W., & Popkin, B. (2012). Time use and physical activity: a shift away from movement across the globe. Obesity Reviews, 13(8), 659-680.

Olshansky, S. J., Passaro, D. J., Hershow, R. C., Layden, J., Carnes, B. A., Brody, J., . . .Ludwig, D. S. (2005). A potential decline in life expectancy in the United States in the 21st century. New England Journal of Medicine, 352(11), 1138-1145.

Sánchez-Miguel, P. A., Leo, F. M., Sánchez-Oliva, D., Amado, D., & García-Calvo, T. (2013). The Importance of Parents’ Behavior in their Children’s Enjoyment and Amotivation in Sports. Journal of human kinetics, 36(1), 169-177.

Sattelmair, J., & Ratey, J. J. (2009). Physically active play and cognition. American journal of play, 3, 365-374.

Toporek, B. (2013). Physical education “The impact of physical education on obesity among elementary school children”. Education Week, 32(33), http://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2013/06/05/33report-2.h32.html

Wittberg, R. A., Northrup, K. L., & Cottrell, L. A. (2012). Children’s aerobic fitness and academic achievement: A longitudinal examination of students during their fifth and seventh grade years. American Journal of Public Health, 102(12), 2303-2307.