Introduction

Governors and state legislators have a unique opportunity to help prepare their constituents for the many ways that work is changing. Outsourcing, global competition, and rapid advances in technology are transforming jobs and industries, leading to economic disruption as old products, jobs, and industries are replaced by new ideas and companies. While these changes have brought economic benefits, they have also contributed to stagnant wages, declining benefits, weakening workplace protections, and, in some cases, job loss. Policymakers, employers, education and training institutions, and other critical stakeholders must work together to create an economy that helps workers take advantage of new and changing jobs, while providing the necessary supports that workers will need to weather the disruptions from changes in technology, trade, and organizational structure.

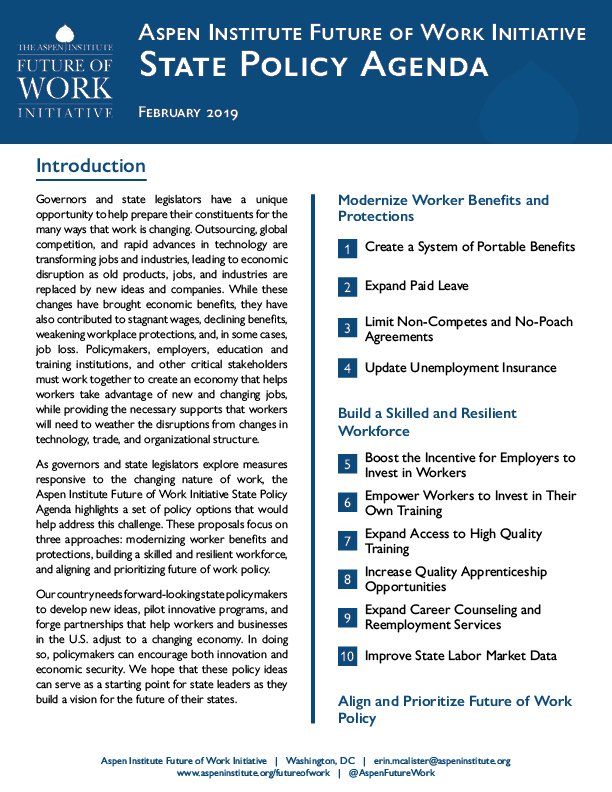

As governors and state legislators explore measures responsive to the changing nature of work, the Aspen Institute Future of Work Initiative State Policy Agenda highlights a set of policy options that would help address this challenge. These proposals focus on three approaches: modernizing worker benefits and protections, building a skilled and resilient workforce, and aligning and prioritizing future of work policy.

Our country needs forward-looking state policymakers to develop new ideas, pilot innovative programs, and forge partnerships that help workers and businesses in the U.S. adjust to a changing economy. In doing so, policymakers can encourage both innovation and economic security. We hope that these policy ideas can serve as a starting point for state leaders as they build a vision for the future of their states.

Modernize Worker Benefits and Protections

Over the course of the 20th century, workers came to rely on their employers to serve as the access point for a range of worker benefits and legal protections. These benefits and protections include the minimum wage, workers’ compensation, the right to organize, healthcare, retirement, disability insurance, and harassment and discrimination protections, among others. These benefits and protections developed individually, the product of historically specific circumstances and legal battles, and were often tied to particular employment arrangements—most commonly traditional, full-time work.

Yet in the last few decades, the traditional employer-employee relationship has weakened. Businesses are less inclined to offer benefits to their employees, and in many cases have created business models that rely on the use of non-traditional work—that is, work done through a temp or contracting agency, on-call work, and independent contracting. For more information on these trends, see the Future of Work Initiative’s publication, Toward a New Capitalism: The Promise and Opportunity of the Future of Work.[1]

As a consequence, even though the U.S. is described as being near full employment, work for many does not include vital benefits and protections, and economic insecurity is on the rise. A decline in employer-provided benefits has been matched by stagnant wages. For most workers, real wages have held steady for decades; the average hourly wage in 2018 had about the same purchasing power that it did in 1964.[2] As wages have held steady, costs of living—including medical costs, housing, and education—have risen.

1. Create a System of Portable Benefits

Background: Over the past thirty years, workers’ access to benefits has declined. The share of workers covered by employer-sponsored health plans has fallen from 75 percent in 1991 to 62 percent in 2018, even as the Affordable Care Act applied a penalty on medium and large businesses that fail to provide coverage to their workers.[3] For retirement, employers have shifted from providing defined benefit pension plans to offering less secure defined contribution plans, to which only a third of workers contribute.[4]

The decline in benefits is felt most acutely among the millions of Americans who work as independent contractors, including freelance journalists, adjunct professors, real estate agents, hair stylists, and those who work for the rapidly growing online labor platforms like Uber, Lyft, TaskRabbit, and Upwork. This work rarely includes employer-provided benefits, exposing independent contractors to high out-of-pocket costs or economic risks of sickness, aging, and on-the-job injuries.

Proposal: State policymakers should work to extend benefits to more people through portable models that: (1) are not tied to any particular job, but rather linked to the worker who can take the benefit from job to job or project to project; (2) support contributions from multiple employers or clients that are proportionate to dollars earned, jobs done, or time worked; and (3) cover any worker, including independent contractors and other non-traditional workers.

Examples: There is already momentum in several states around portable benefits. Legislators in Washington, New Jersey, Georgia, and Massachusetts have introduced bills to either create portable benefits systems or start innovation funds to experiment with different portable benefits models.[5] New York’s Black Car Fund, established in 1999 and expanded to the entire state in 2017, serves as an example of an existing portable benefits model. The Fund allows professional passenger car drivers—traditionally independent contractors—to access workers’ compensation coverage, and more recently vision and telemedicine benefits, through a mandatory passenger surcharge. In the retirement space, ten states have implemented programs, often called “Secure Choice,” that attempt to make retirement plans more portable and universally accessible.[6]

2. Expanding Paid Leave

Background: Balancing work and family responsibilities is a significant challenge for millions of American families. Fully two-thirds of households today include two working parents, and the percentage of households that are led by single mothers or fathers is rising.[7] And with an aging population, American families face increasing eldercare needs.[8]

However, just 17 percent of the workforce has access to paid family leave.[9] This is partly the result of the U.S. being the only high-income country—and one of only a few countries in the world—that does not provide workers at least some guaranteed paid family leave. The federal 1993 Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) ensures that employees cannot be fired for taking unpaid leave, and recent estimates suggest just 59 percent of employees are FMLA eligible.[10] Moreover, there is no federal guarantee for paid leave.

State level paid leave programs are often designed for workers in traditional, stable, full-time employment. Work history requirements, firm size restrictions, and limiting eligibility to those in traditional employment ends up excluding self-employed workers, employees at small businesses, and many part-time workers.[11] Ensuring universal access to paid family and medical leave should be a key component of a future of work agenda to update the social contract for workers in the 21st century.

Proposal: State policymakers should create paid leave benefit programs to improve economic security for workers when they need to care for themselves and their families. These programs should be portable so that earned benefits can be taken from one job to the next without a lapse in coverage, and allow contributions across multiple income sources. They should include independent contractors. This can be done by allowing independent contractors to opt into the system, or, to encourage uptake, requiring businesses who rely heavily on independent contractors to auto-enroll their workers and pay the cost of their contractors’ paid leave coverage.[12]

Examples: In 2018, Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker signed a new paid leave law, guaranteeing eligible workers up to 12 weeks of paid family and medical leave to care for a sick family member or stay home with a newborn child, and up to 20 weeks of paid leave for a serious illness. The new legislation, which will take effect in 2021, makes Massachusetts the seventh state to mandate access to paid leave. California, New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island have created programs in the past 20 years, while new programs in the District of Columbia and Washington will take effect in 2020.[13]

3. Limit Non-Competes and No-Poach Agreements

Background: Many jobs do not provide economic security or a clear pathway to increased earnings. To find better pay and benefits, workers may need to find a new employer. Through the use of non-compete clauses and no-poach agreements, though, businesses are making it increasingly difficult to switch jobs.

Non-competes are clauses in employment contracts that restrict a worker from joining or founding a rival company for a certain period of time after leaving the company, while no-poach agreements are agreements between employers promising not to poach each other’s workers. These contracts were initially introduced to protect legitimate business interests, such as trade secrets and intellectual property.

But the usage of these contracts has exploded in recent years. Surveys find that between 20 and 25 percent of the workforce is bound by a non-compete restriction, either from their previous job or current job, while nearly 60 percent of major franchises are covered by no-poach agreements.[14] Because taking a new job is the primary way that workers achieve wage growth, these restrictions depress lifetime earnings and contribute to the experience of wage stagnation.[15]

Proposal: To support a more dynamic economy, workers should be allowed to move more freely between jobs and companies. State policymakers should prohibit non-compete clauses for low-income workers and ban no-poach agreements, including those between separate franchises with a single chain.[16]

Examples: California has a long-standing ban on the enforcement of non-competes (which many economists credit for the success of the state’s tech industry). In the last three years, four other states—Hawaii, Utah, Idaho, and Illinois—have passed laws that restrict the usage of non-compete clauses, while New Hampshire, Pennsylvania and Vermont have considered legislation.[17] Similarly, a coalition of 11 state attorneys general is investigating no-poach agreements at several chains, and under threat of legal action, numerous fast food chains recently agreed to end no-poach agreements.[18]

4. Update Unemployment Insurance

Background: Unemployment Insurance (UI) was designed for traditional, full-time work and does not adequately cover workers in non-traditional jobs. Workers must have a W-2 employment relationship with their employer to have UI coverage—excluding independent contractors entirely. Non-traditional workers who are W-2 employees—such as temp-agency workers, on-call workers, subcontracted workers, multiple job holders, and part-time workers—are covered by UI, but they typically receive less coverage compared to traditional workers.

In addition, UI does not help unemployed workers move into non-traditional jobs. Non-traditional work can provide a path back to stable earnings, by helping workers maintain existing skills, acquire new skills, and earn vital income as they search for traditional employment; or by helping them transition into a permanent career in self-employment. But UI eligibility rules often discourage unemployed Americans from seeking and engaging in non-traditional work, and the workforce system rarely trains workers for—or helps them find—this type of work.

UI coverage is also shrinking. The percent of unemployed workers who receive unemployment benefits fell from an average of about 50 percent in the 1950s, to about 35 percent in 1990s, to under 30 percent since 2010.[19] These coverage gaps leave today’s workers vulnerable and insecure.

Proposal: State policymakers should create new protections for workers who are ineligible for UI by experimenting with expansion to cover independent contractors with a history of consistent, stable earnings. UI should also be reformed to allow unemployed workers to start a business or participate in non-traditional work if these opportunities are available. In addition, state policymakers should consider creating a jobseekers’ allowance to provide a financial support to low- and middle-income workers looking for work, including independent contractors, new labor market entrants, and other workers ineligible for UI.[20] The Aspen Institute Future of Work Initiative published a report—Modernizing Unemployment Insurance for the Changing Nature of Work—that explores a variety of policy solutions to reform UI so that it can better serve a broader population of workers.[21]

Examples: Nine states currently have active Self-Employment Assistance (SEA) programs, which allow unemployed workers to continue receiving UI benefits while starting a business rather than seeking full-time W-2 employment.[22] Many states already allow UI recipients to seek part-time work, but 21 states still require UI beneficiaries to pursue full-time work to remain eligible for benefits, even if their benefits were earned through part-time work.[23]

Build a Skilled and Resilient Workforce

Technology, outsourcing, and global competition will continue to change and disrupt work, causing some jobs to decline, others to increase, and new roles to emerge in new or existing industries. Automation alone could partially automate over 90 percent of occupations over the next twelve years.[24] As these trends become more widespread, the task makeup of jobs will shift, often requiring workers to develop new skills.

These changes present challenges as well as opportunities. To keep up with the pace of change, workers will need to be lifelong learners, adapting to the shifting demands of the labor market, and employers will need to play a larger role in helping their employees access learning opportunities. Workers who can learn new skills stand to benefit from higher wages and more meaningful work. Policymakers have an important role to play in helping workers access—and employers offer—effective, affordable, and skills-based training and new career pathways.

5. Boost the Incentive for Employers to Invest in Workers

Background: Employers are uniquely positioned to play an important role in preparing the workforce for lifelong learning: they have the scale, the resources, and the insight into changing skills needs. Unfortunately, the available data suggest that employer investment in worker training is declining.[25]

In part, the decline in employer-provided training can be explained by changes in the employer-employee relationship over the past 40 years. Because the benefits of training reside primarily with the worker rather than with the business, there will always be a portion of the investment that benefits the overall economy but not the business itself. If businesses plan to retain employees over a long period, they will benefit directly from their training investments. But as relationships between workers and businesses become less stable and more short-term, businesses have a more difficult time capturing the return on their training investments. The result is less investment in training even as employers are in need of a more highly-skilled workforce.[26]

Proposal: State policymakers should create a business tax credit to offset a portion of the cost of new training activities for non-highly compensated workers. The Worker Training Tax Credit would mirror the policy design of the popular federal R&D Tax Credit. To ensure that low- and middle-income workers are the primary beneficiaries, it should restrict eligibility above a certain wage threshold. See the Future of Work Initiative’s issue brief, Worker Training Tax Credit: Promoting Employer Investments in the Workforce, for more policy details.[27]

Examples: Connecticut, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, Rhode Island, and Virginia provide businesses with tax credits for training investments that range from 5 percent to 50 percent of training expenses.[28] In New Jersey, State Senator Troy Singleton has introduced a version of a worker training tax credit, and in Virginia, a proposal by House Delegate Kathy Byron to reform the state’s existing Worker Retraining Tax Credit to better conform to this proposal recently passed both legislative chambers.[29] Federal legislation to create a Worker Training Tax Credit was also introduced in the U.S. Senate (S.2048) and House (H.R.5516) in the last Congress.[30]

6. Empower Workers to Invest in Their Own Training

Background: Employers play a unique and vital role in workforce training. But while some workers will be able to rely on employers to help them acquire new skills, others will not have access to employer-provided training. All workers should have financial assistance and a portable system to help them access new education and training opportunities.

Proposal: State policymakers should create worker-controlled Lifelong Learning and Training Accounts (LLTAs). These accounts would be funded by workers, employers, and government, and could be used by workers to pay for education and training opportunities over the course of their career. They should target their benefits to low- and middle-income workers through a government matching contribution that phases down as income rises. See the Future of Work Initiative’s issue brief, Lifelong Learning and Training Accounts: Helping Workers Adapt and Succeed in a Changing Economy, for more policy details.[31]

Examples: Lifelong Learning Account demonstration programs have been implemented in several states and cities, including Maine, Washington, Chicago, and New York City. Washington state’s Lifelong Learning Program is a voluntary employee benefits program where employers agree to match their employees’ contributions to a Lifelong Learning Account. The fund is portable and can be used for any education or training investment.[32] In Massachusetts, State Senator Eric Lesser has proposed legislation to establish a Lifelong Learning and Training Account program.[33] Federal legislation was also proposed in the U.S. Senate (S.3145) and House (H.R.6250) last session.[34]

7. Expand Access to High Quality Training

Background: Community colleges are well positioned to provide in-demand skills training. There are 1,047 public community colleges across the country, and the education and training they provide contributes to better economic outcomes.[35] For example, an analysis of California community college programs found that their career and technical programs raised earnings by 14 percent (for certificates of less than 18 units) to 45 percent (for associate degrees).[36] Unfortunately, community college funding has been sharply cut over the past two decades. Since 2001, state and local funding per full-time equivalent student has declined by 30 percent (after adjusting for inflation).[37] Federal funding has risen over this time period, but not enough to fill the funding gap.

At the same time, private and non-profit training providers are playing an important role in offering innovative and flexible training programs. Similar to community colleges, the effectiveness of these providers can vary. Organizations such as Year Up, Per Scholas, and General Assembly appear to show positive results for their participants.[38] Other research, however, that has focused on students who attend for-profit certificate programs has shown no discernable increase in earnings after graduation compared to similar students who do not attend a training program at all. An analysis of for-profit certificate programs found that after taking into account the cost of the program, the majority of students were worse off financially.[39]

Proposal: State policymakers should identify strategies to increase funding for community colleges to provide high-quality, in-demand skills training. The funding should be based on (1) characteristics of the student body (with greater funding allocated to schools with greater shares of students from disadvantaged backgrounds); (2) the labor market conditions in the local community, such as the local employment rate; and (3) demonstrated improvements in student retention and completion.[40] The Aspen Economic Strategy Group has proposed increased federal funding for community colleges to boost educational attainment, expand opportunities for mid-career skills development, and provide better career pathways for workers without four-year college degrees.[41]

In addition, state policymakers should explore ways to improve the quality of private training by encouraging private training providers to design tuition systems based on outcomes rather than fixed prices. Some training providers have established outcome-based payment systems known as Income Share Agreements (ISAs), in which the provider will forego a portion of the tuition, and in return, the students promise to pay a percentage of their future earnings back to the provider for a period of time after graduation. Moving the private training market toward greater use of ISAs would reward effective training programs and disadvantage providers of poor-quality training, while maintaining the incentive for private providers to develop innovative offerings.

This policy approach could begin by providing regulatory guidance. In many states, ISAs are often unregulated. In response, policymakers could clarify what regulations apply to private ISAs in order to provide certainty to users of ISA’s regarding how the terms and conditions of an ISA could work and to ensure that students are protected from potential abuse.

Examples: In the last decade, many states have developed free or debt-free tuition programs for their public institutions, often community colleges. These free college policies, often known as “College Promise” programs, have proliferated in conservative and liberal states alike. Early adopters include Delaware and Tennessee, and as of July 2018, nineteen states across the country have such programs.[42] Eight of these have been enacted in the last two years, and many other states, including California, Rhode Island, Washington, and Michigan are considering either adopting new programs or expanding their existing programs.[43]

Virginia recently incorporated outcome-based payments into how it funds community college training. Under the New Economy Workforce Credential Grant (NEWCG), which was adopted in 2016, the state pays a portion of the cost for a student to obtain an eligible credential.[44] Eligible training is non-credit but leads to a workforce credential in a high-demand field.[45] The student pays one-third of the cost, and the state will pick up the remaining two-thirds of the cost (up to $3,000) if the student graduates and receives the credential.

Many educational institutions have adopted ISAs. Holberton School in San Francisco offers a two-year training program in software engineering, while Kenzie Academy in Indianapolis offers coding and computer science courses that are coupled with on-the-job training through paid apprenticeships.[46] The courses are tuition-free, with students instead required to pay back a percentage of their income over time through an ISA—and if they make below a certain income threshold, they are not required to make payments. Traditional higher education institutions have also adopted this model: Purdue University launched its ISA program (Back a Boiler) in 2016, while the University of Utah, Colorado Mountain College, and others have since followed suit.

8. Increase Quality Apprenticeship Opportunities

Background: Apprenticeships can offer clear advantages over other forms of training. First, the involvement of local employers in developing apprenticeship programs ensures that curricula are aligned to the specific needs of the employer. Second, apprenticeships pay workers while they are in the program, reducing the cost of pursuing training. Third, the work-based instruction method can be an effective form of teaching, especially for those who have difficulty with traditional classroom learning. And finally, because apprenticeships incorporate employment, workers who have completed an apprenticeship program already have a job when they graduate.

Studies have shown that apprenticeships are effective in training workers for and placing them in well-paying jobs. A 2012 study found that registered apprentices earned roughly $240,000 more over their lifetimes than similar workers who had not gone through such programs, with the benefits to society exceeding the costs by nearly $50,000.[47] Nearly nine out of ten apprentices are employed after completing their apprenticeships with an average starting wage of over $50,000.[48] Unfortunately, apprenticeships are relatively scarce in the U.S., representing only 0.3 percent of the labor force—far below Canada (2.2 percent), Britain (2.7 percent), Australia (3.7 percent), and Germany (3.7 percent).[49]

Proposal: State policymakers should consider three complementary approaches to encouraging apprenticeship programs: (1) create a state department or office dedicated to actively encouraging and assisting businesses in establishing apprenticeship programs; (2) provide a tax credit to encourage businesses to establish apprenticeship programs; and (3) provide marketing assistance to boost awareness of apprenticeship opportunities.

Examples: According to the U.S. Department of Labor, 12 states currently offer tax credits to employers that hire apprentices, and another 12 states offer tuition support for registered apprentices.[50] For example, in Montana, employers who hire workers through the Montana Registered Apprenticeship unit are eligible for a $750 tax credit.[51] In 2018, Massachusetts adopted a tax credit for employers who sponsor apprenticeship programs equal to $4,800 or 50 percent of wages paid to each apprentice.[52]

South Carolina has adopted a comprehensive and successful approach to encouraging apprenticeships: through a combination of tax credits, apprenticeship consultants that work with businesses to facilitate the registration process, and an engaged community college system, South Carolina’s apprenticeship enrollment has expanded from roughly 800 in 2007 to nearly 30,000 in 2018.[53]

9. Expand Career Counseling and Reemployment Services

Background: In today’s economy, transitioning to a new job can involve a number of challenges, including identifying new opportunities, understanding what skills or job experiences are needed for a new job, and where to acquire those skills if needed. This type of transition is particularly difficult if one has lost a job and needs to find work quickly. Though challenging, these transitions are possible: according to a recent analysis by the World Economic Forum and the Boston Consulting Group, 96 percent of workers currently holding jobs at risk of technological disruption should be able to find other jobs that fit their skill set.[54] But most of these new jobs are outside the original job’s cluster of related professions, meaning that displaced workers may not be aware of them.

Career counseling and other reemployment services—such as job listings, job search assistance, and referrals to employers—are delivered to workers through more than 2,500 American Job Centers (AJCs) across the country. A study commissioned by the U.S. Department of Labor found that these reemployment services represent a fast and cost-effective approach to helping displaced workers find work, and result in savings to the Unemployment Insurance program that exceed the cost of the services.[55] The 2016 Gold Standard Program Evaluation of the federal workforce development program found that workers who used staff-supported services, which includes career counseling, experienced 17 percent higher earnings compared to workers who only accessed self-service resources.[56] However, federal funding has been decreasing over time: federal Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act grants to states—which form the core of the national public workforce system and fund AJCs—have been cut by over 40 percent since 2001.[57]

Proposal: State policymakers should boost funding for AJCs, in particular to support additional career counselors. Moreover, states should provide robust training to counselors to better use technology and data to improve their ability to guide workers through career transitions and find them effective and quality jobs.

Examples: Colorado and Indiana have invested in improving the quality of job coaching by working with the Markle Foundation’s Skillful Initiative to develop the Career Coaching Corps.[58] This program connects counselors from AJCs, community colleges, high schools, and nonprofit organizations in a “community of practice” to ensure high-quality standards and best practices are disseminating through a “train the trainer” approach, allowing coaches across the state to better serve workers in transition. Participating counselors also learn how to better use new technologies—such as SkillsEngine, mySkills, myFuture, edX, LinkedIn, and CSMlearn—and labor market data to help workers find training and well-paying jobs.

Some states have emphasized career counseling outside of the public workforce system. For example, Pathways to Prosperity provides middle and high school students with early and sustained career counseling and workplace-learning opportunities. Launched in 2012 by Jobs for the Future and the Harvard Graduate School of Education, it now operates at schools in 14 states.[59]

10. Improve State Labor Market Data

Background: Labor market data help workers, students, employers, workforce investment boards, and state agencies make informed decisions. Workers need accurate and timely information on how industries and occupations are changing, which skills are increasingly in demand, where skill mismatches exist, and how to find new job opportunities. Education and training providers, in collaboration with employers, need to understand how skill needs are changing to better design training programs. And finally, government and community leaders would benefit from an improved understanding of how automation and other technologies are changing the economy and what populations are at greatest risk of disruption in order to ensure training systems and safety net programs can provide workers the tools they need to stay employed.

Detailed data on local and regional economies is often nonexistent or inaccessible. Better data would benefit local, state and national stakeholders as it would improve understanding of how economic forces like automation are affecting local and regional economies, to best target policymaking, service offerings, and delivery.

Moreover, students often have difficulty assessing the quality of education and training programs because they frequently lack standardized and verifiable information about program outcomes. But state data systems are often not prepared to provide this information. The most reliable data source for post-graduation employment outcomes is workforce administrative data—usually from the Unemployment Insurance program’s wage records—but most states do not include enough data elements to allow for full analysis of the effectiveness of training programs, and some do not link this employment data to educational data at all.

Proposal: State policymakers should take steps toward improving their data collection and usage.

First, state policymakers should add new data elements in state UI wage records, such as occupational title (using standardized occupational codes), hours worked, credential completion, and work site. Asking employers to report this type of information would enable the production of detailed state and local area data and provide a clearer picture of local and regional labor markets.[60]

Second, this newly enriched UI data and other administrative data can then be used to create training program effectiveness data if they are matched with education program data through state longitudinal data systems (SLDS). States should establish an SLDS and ensure the agency running it has a close working relationship with the state agencies that are providing administrative data. If presented in a simple and standardized format, this training effectiveness data could help students make informed decisions about which training to seek.[61] If they are not already doing so, states should also prioritize sharing their UI data with other states and the federal government.

Third, state policymakers should increase funding for state labor market information systems. These systems produce, disseminate, and analyze state and local labor force statistics, including the identification of “in-demand occupations and industries,” and enable employers, students, workers, workforce investment boards, government agencies, education providers, and other state and local labor market participants to make informed decisions.

And fourth, states should develop a more effective and transparent skills-based labor market. By working with employers and educational institutions to make skills a common language and currency for job postings and education and training programs, workers can more easily show what skills they have, learn what skills employers are looking for, learn which programs will help them acquire those skills, and better match with jobs.

Examples: Louisiana, Oregon, Washington, and Alaska currently collect additional data elements, including occupational title.[62] A 2014 BLS survey found that states that collected enhanced wage records “reported that the data were extremely helpful in estimating hourly earnings, understanding career progression from occupation to occupation, assessing the effectiveness of workforce training, and making occupational projections.”[63]

A number of states have taken steps toward a more skills-based labor market. For instance, Colorado, and more recently Indiana, have worked with the Markle Foundation’s Skillful Initiative—in partnership with Microsoft, LinkedIn and other partners—to develop a more effective and transparent skills-based labor market.[64] In February 2019, 20 Governors helped launch the Skillful State Network in an effort to scale the model.[65] But achieving that level of transparency—and linking the theory up with actual hiring decisions in practice—can be quite difficult without the underlying data and information on skill needs and gaps.

Align and Prioritize Future of Work Policy

Policymakers face significant challenges in responding to the rapidly changing nature of work. Development and evaluation of additional policy solutions will require input and participation from a range of key stakeholders, including business, labor, workforce, education, researchers, and policymakers. States should consider designating a responsible body or party to build better awareness of the challenges and involve these stakeholders in the development of solutions.

Several different approaches could bring together stakeholders and help inform future policy. The goal of any approach should be to build a composite view of the challenges ahead, develop a shared understanding of existing data and future trends, and identify potential policy and programmatic solutions. The designated body or party could also ensure that any new proposals align with and build on existing infrastructure and programming, and help foster connections between stakeholders that will be necessary to successfully carry out agreed upon strategies.

One approach is to create a short-term commission or task force. States could convene short-term bodies bringing together a range of stakeholders—workers, advocates, employers, and other policymakers—to answer a set of core questions. Indiana initiated a Future of Work Taskforce through action of the state’s standing Workforce Innovation Council in 2017, and Washington created a Future of Work Task Force through the passage of legislation in March 2018. New Jersey also created a Future of Work Task Force through Executive Order of the Governor in 2018.[66] Similar legislation was introduced in California last year and in Massachusetts this year.[67]

A second option is to create a standing council or board. States could create a permanent organization to hold responsibility for future of work policy issues. Similar to a short-term commission or task force, this body would coordinate research and policy as it relates to the future of work. For example, Indiana has established a new Governor’s Workforce Cabinet with ongoing responsibility for future of work and related issues. Similarly, policymakers in Washington are considering a bill that would create tri-partite wage and standards boards in four sectors with a high concentration of independent contractors. The boards would examine conditions in those sectors and address pressing challenges in a time-sensitive manner.

The focus of the commission or task force should be tailored as narrowly as possible to drive toward concrete solutions. Example areas of focus include (1) the impact of technology on the labor market, (2) the prevalence of non-traditional work and shifts in work arrangements, (3) education and training approaches to future-proof the workforce, and (4) changes to the strength and nature of the social contract. The commission could come to a clear understanding of the issues through data, share insights with key stakeholders, and develop and submit recommendations on a policy framework to the Legislature and Governor.

A third option is to create a dedicated future of work position. A state could create a full- or part-time position focused on how to prepare for the future of work, either as an advisor to the Governor or as a part of a state’s Department of Labor. For example, in 2017 the Virginia General Assembly elevated the state’s Chief Workforce Development Advisor to a Cabinet-level position, with the responsibility to help coordinate efforts across various agencies and to address the needs of a changing workforce.[68]

State policymakers can also engage organizations that work across states to better inform future of work policy initiatives: for example, the National Governors Association Center for Best Practices started a multi-state collaborative to understand and support the on-demand workforce in 2018.[69]

[1] Aspen Institute Future of Work Initiative. 2017. “Toward a New Capitalism: The Promise of Opportunity and the Future of Work.” January. https://www.aspeninstitute.org/publications/the-promise-of-opportunity-and-the-future-of-work/.

[2] DeSilver, Drew. 2018. “For most U.S. workers, real wages have barely budged in decades.” Pew Research Center. August. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/08/07/for-most-us-workers-real-wages-have-barely-budged-for-decades/.

[3] Bureau of Labor Statistics. “National Compensation Survey.” U.S. Department of Labor. https://www.bls.gov/ncs/.

[4] Bureau of Labor Statistics. “National Compensation Survey.” U.S. Department of Labor.

Bhattarai, Abha. 2017. “Two-thirds of Americans aren’t using this easy way to save for retirement.” The Washington Post. February 22. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/get-there/wp/2017/02/22/two-in-three-americans-will-never-retire-at-this-rate/.

[5] State of Washington. 2019. “HB 1601 – Creating the universal worker protections act.” 66th Legislature. Introduced January 25, 2019. https://app.leg.wa.gov/billsummary?BillNumber=1601&Initiative=false&Year=2019.

State of New Jersey. 2018. “S67 – Establishes system for portable benefits for workers who provide services to consumers through contracting agents.” 218th Legislature. Introduced January 9, 2018. https://www.njleg.state.nj.us/2018/Bills/S0500/67_I1.HTM.

State of Georgia. “SB 475 – Independent Contractors; certain employment benefits; funding; administration; and eligibility; provide.” 2017-2018 Regular Session. Introduced February 21, 2018. http://www.legis.ga.gov/Legislation/en-US/display/20172018/SB/475.

Commonwealth of Massachusetts. “SD 1100 – An Act establishing a portable benefits for independent workers innovation fund.” 119st General Court. Introduced January 17, 2019. https://malegislature.gov/Bills/191/SD1100.

[6] These states are Oregon, Illinois, California, Connecticut, Maryland, New York, Washington, New Jersey, Vermont, Massachusetts.

[7] Parker, Kim, and Gretchen Livingston. 2018. “7 facts about American dads.” Pew Research Center. June. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/06/15/fathers-day-facts/.

Pew Research Center. 2015. “Parenting in America.” December. http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2015/12/17/parenting-in-america/.

[8] Houser, Ari, Mary Jo Gibson, and Donald L. Redfoot. 2010. “Trends in Family Caregiving and Paid Home Care for Older People with Disabilities in the Community.” AARP Public Policy Institute. September. https://assets.aarp.org/rgcenter/ppi/ltc/2010-09-caregiving.pdf.

[9] Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2018. “Leave benefits: Access.” From the Employee Benefits Survey. U.S. Department of Labor. March. https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2018/ownership/civilian/table32a.htm.

[10] Based on Employee Survey data from 2012. Per 2.2.1, an estimated 59.2 percent of current employees are eligible for FMLA—those whose worksites had 50 or more employees within 75 miles, had continuously worked for the same worksite for the past 12 months, and were always a full-time employee or worked at least 1,250 hours over the past 12 months.

Klerman, Jacob Alex, Kelly Daley, and Alyssa Pozniak. 2012. “Family and Medical Leave in 2012: Technical Report.” Abt Associates. September. https://www.dol.gov/asp/evaluation/fmla/FMLA-2012-Technical-Report.pdf.

[11] To be eligible for FMLA coverage, a worker must: 1) be an employee as defined under the FLSA; 2) work for an employer with at least 50 employees; 3) have worked for that employed for the past 12 months; and 4) have worked at least 1250 hours for that employer over the past 12 months. This explicitly excludes self-employed workers and those working for small employers, and implicitly excludes many of those who work temporary, seasonal, and part-time jobs.

[12] Recent history suggests that opt-in systems suffer from low utilization rates. For example in California only 413 self-employed workers accessed paid leave over the past ten years (2007-2017).

PL+US. 2018. “Left Behind: How California’s Paid Family Leave Program is Failing People in Low-Wage Jobs and the Gig Economy.” September. https://paidleave.us/s/plusleft_behind_20180919_V6.pdf.

Massachusetts, in contrast, decoupled contributions from coverage by requiring contributions from businesses that are heavily reliant on independent contractors. The independent contractors still must enroll, but many will already have had their contribution paid by the business they work for.

Commonwealth of Massachusetts. 2019. “Paid Family Medical Leave for employers FAQ.” https://www.mass.gov/info-details/paid-family-medical-leave-for-employers-faq.

[13] Washington, the District of Columbia, and Massachusetts will begin collecting premiums in 2019, 2019, and 2020 respectively, with paid leave benefits beginning to be paid out in 2020, 2020, and 2021 respectively.

[14] Starr, Evan. 2019. “The Use, Abuse, and Enforceability of Non-Compete and No-Poach Agreements.” Economic Innovation Group. February. https://eig.org/noncompetesbrief.

Krueger, Alan, and Eric Posner. 2018. “A Proposal for Protecting Low‑Income Workers from Monopsony and Collusion.” The Hamilton Project, Brookings Institution. February. http://www.hamiltonproject.org/papers/a_proposal_for_protecting_low_income_workers_from_monopsony_and_collusion.

[15] Balasubramanian, Natarajan, Jin Woo Chang, Mariko Sakakibara, Jagadeesh Sivadasan, and Evan Starr. 2017. “Locked In? The Enforceability of Covenants Not to Compete and the Careers of High-Tech Workers.” U.S. Census Bureau Center for Economic Studies Paper. January. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2905782.

[16] Krueger, Alan, and Eric Posner. 2018. “A Proposal for Protecting Low‑Income Workers from Monopsony and Collusion.” The Hamilton Project, Brookings Institution. February. http://www.hamiltonproject.org/papers/a_proposal_for_protecting_low_income_workers_from_monopsony_and_collusion.

Walter, Karla. 2019. “The Freedom to Leave: Curbing Noncompete Agreements to Protect Workers and Support Entrepreneurship.” Center for American Progress. January. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/reports/2019/01/09/464831/the-freedom-to-leave/.

[17] Marx, Matt. 2018. “Reforming Non-Competes to Support Workers.” The Hamilton Project, Brookings Institution. February. https://www.brookings.edu/research/reforming-non-competes-to-support-workers/.

Schwarz, Daniel, Martha Van Oot, Erik Winton, and Colin Thakkar. 2018 “Three States May Restrict Use of Employment Noncompete Agreements.” Society for Human Resource Management. January. https://www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/legal-and-compliance/state-and-local-updates/pages/states-may-restrict-use-of-employment-noncompete-agreements.aspx.

[18] Abrams, Rachel. 2018. “‘No Poach’ Deals for Fast-Food Workers Face Scrutiny by States.” The New York Times. July 9. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/09/business/no-poach-fast-food-wages.html/.

Walter. 2019. “The Freedom to Leave.” Center for American Progress.

[19] McMurrer, Daniel, and Amy Chasanov. 1995. “Trends in Unemployment Insurance Benefits.” Monthly Labor Review, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. September. https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/1995/09/art4full.pdf.

McHugh, Rick, and Will Kimball. 2015. “How Low Can We Go? State Unemployment Insurance Programs Exclude Record Numbers of Jobless Workers.” Economic Policy Institute. March. http://www.epi.org/publication/how-low-can-we-go-state-unemployment-insurance-programs-exclude-record-numbers-of-jobless-workers/.

The lowest rates of annual average insured unemployment in the U.S. have all come since 2011.

U.S. Department of Labor. 2019. “Unemployment Insurance Chartbook.” Last accessed February 11, 2019. https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/chartbook.asp.

[20] West, Rachel, Indivar Dutta-Gupta, Kali Grant, Melissa Boteach, Claire McKenna, and Judy Conti. 2016. “Strengthening Unemployment Protections in America.” Center for American Progress, National Employment Law Project, and Georgetown Center on Poverty and Inequality. June. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/poverty/reports/2016/06/16/138492/strengthening-unemployment-protections-in-america/.

[21] McKay, Conor, Ethan Pollack, and Alastair Fitzpayne. 2018. “Modernizing Unemployment Insurance for the Changing Nature of Work.” Aspen Institute Future of Work Initiative. January. https://www.aspeninstitute.org/publications/modernizing-unemployment-insurance/.

[22] These states include Delaware, Maine, Mississippi, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island. As of this paper’s writing, Louisiana also has an SEA program in law, however it is non-operational.

U.S. Department of Labor. 2017. “Comparison of State Unemployment Insurance Laws.” https://workforcesecurity.doleta.gov/unemploy/pdf/uilawcompar/2017/complete.pdf.

[23] U.S. Department of Labor. 2017. “Comparison of State Unemployment Insurance Laws.”

[24] According to McKinsey Global Institute, at least 10 percent of work hours are automatable in 91 percent of jobs.

Manyika, James, Susan Lund, Michael Chui, Jacques Bughin, Jonathan Woetzel, Parul Batra, Ryan Ko, and Saurabh Sanghvi. 2017. “Jobs Lost, Jobs Gained: Workforce Transitions in a Time of Automation.” McKinsey Global Institute. December. https://www.mckinsey.com/global-themes/future-of-organizations-and-work/what-the-future-of-work-will-mean-for-jobs-skills-and-wages.

[25] Council of Economic Advisors. 2015. “Economic Report of the President.” February. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/docs/cea_2015_erp_complete.pdf.

Waddoups, C. Jeffrey. 2016. “Did Employers in the United States Back Away from Skills Training during the Early 2000s?” ILR Review 69, no. 2 (March): 405-434. http://ilr.sagepub.com/content/69/2/405.

[26] As economist Lisa Lynch writes, “Employees who are perceived to have higher turnover rates, such as low-wage and low-skilled workers, are less likely to receive employer-provided training.. in addition, training itself may contribute to employee turnover: if new skills are of value to other employers, then firms risk having their trained employee hired away.”

Lynch, Lisa. 2004. “Development Intermediaries and the Training of Low-Wage Workers.” In Emerging Labor Market Institutions for the Twenty-First Century, edited by Richard B. Freeman, Joni Hersch, and Lawrence Mishel. University of Chicago Press. December. https://www.nber.org/chapters/c9959.pdf.

[27] Fitzpayne, Alastair, and Ethan Pollack. 2018. “Worker Training Tax Credit: Promoting Employer Investments in the Workforce.” Aspen Institute Future of Work Initiative. August. https://www.aspeninstitute.org/publications/worker-training-tax-credit-update-august-2018/.

[28] Fitzpayne and Pollack. 2018. “Worker Training Tax Credit.” Aspen Institute Future of Work Initiative.

[29] State of New Jersey. “S3337 – Provides credits against corporation business and gross income taxes for certain employers that invest in human capital.” 218th Legislature. Introduced January 17, 2019. https://www.njleg.state.nj.us/2018/Bills/S3500/3337_I1.HTM.

Commonwealth of Virginia. “HB 2539 – Worker training investment tax credit.” 2019 Session. Introduced January 9, 2019. http://lis.virginia.gov/cgi-bin/legp604.exe?191+sum+HB2539.

[30] U.S. Senate. “S.2048 – Investing in American Workers Act.” 115th Congress. Introduced October 31, 2017. https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/senate-bill/2048.

U.S. House of Representatives. “H.R.5516 – Investing in American Workers Act.” 115th Congress. Introduced April 13, 2018. https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/5516.

[31] Fitzpayne, Alastair, and Ethan Pollack. 2018. “Lifelong Learning and Training Accounts: Helping Workers Adapt and Succeed in a Changing Economy.” Aspen Institute Future of Work Initiative. May. https://www.aspeninstitute.org/publications/lifelong-learning-and-training-accounts-2018/.

[32] Workforce Training & Education Coordinating Board. “Where can Lifelong Learning Lead You?” State of Washington. http://www.wtb.wa.gov/lifelonglearningaccount.asp.

[33] Commonwealth of Massachusetts. “SD.1155 – An Act to establish a Lifelong Learning and Training Account Program.” 191st General Court. https://malegislature.gov/Bills/191/SD1155.

[34] U.S. Senate. “S.3145 – Skills Investment Act of 2018.” 115th Congress. Introduced June 27, 2018. https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/senate-bill/3145/.

U.S. House of Representatives. “H.R.6250 – Skills Investment Act of 2018.” 115th Congress. Introduced June 27, 2018. https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/6250

[35] Office of Career, Technical, and Adult Education. “Community College Facts at a Glance.” U.S. Department of Education. Last accessed February 10, 2019. https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ovae/pi/cclo/ccfacts.html.

[36] Huff Stevens, Ann, Michal Kurlaender, and Michel Grosz. 2015. “Career Technical Education and Labor Market Outcomes: Evidence from California Community Colleges.” Working Paper 21137, National Bureau of Economic Research. April. https://www.nber.org/papers/w21137.pdf.

[37] Aspen Economic Strategy Group. 2019. “Expanding Economic Opportunity for More Americans.” February. https://www.aspeninstitute.org/longform/expanding-economic-opportunity-for-more-americans/.

[38] General Assembly. 2018. “General Assembly’s Student Outcomes Report.” May. https://ga-core.s3.amazonaws.com/cms/files/files/000/004/774/original/180511_OutcomesReport1516.pdf.

Fein, David, and Jill Hamadyk. 2018. “Bridging the Opportunity Divide for Low-Income Youth: Implementation and Early Impacts of the Year Up Program.” May. Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.yearup.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Year-Up-PACE-Full-Report-2018.pdf.

Weise, Michelle, Andrew Hanson, Allison Salisbury, and Kathy Qu. 2019. “On-ramps to Good Jobs: Fueling Innovation for the Learning Ecosystem of the Future.” https://go.stradaeducation.org/on-ramps.

[39] Riegg Cellini, Stephanie. 2018. “Gainfully employed? New evidence on the earnings, employment, and debt of for-profit certificate students.” Brown Center on Education Policy, Brookings Institution. February. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/brown-center-chalkboard/2018/02/09/gainfully-employed-new-evidence-on-the-earnings-employment-and-debt-of-for-profit-certificate-students/.

[40] A version of this proposal was originally proposed by the Aspen Economic Strategy Group in a recent report.

[41] Aspen Economic Strategy Group. 2019. “Expanding Economic Opportunity for More Americans.”

[42] Mishory, Jen. 2018. “Free College:” Here to Stay?.” The Century Foundation. July. https://tcf.org/content/report/free-college-stay/.

[43] Hart, Angela. 2019. “Newsom proposes free community college in California.” Politico. January 4. https://www.politico.com/states/california/story/2019/01/04/newsom-proposes-free-community-college-in-california-771230.

Borg, Linda. 2019. “Raimondo’s budget plan would extend free tuition to Rhode Island College.” Providence Journal. January 17. https://www.providencejournal.com/news/20190117/raimondos-budget-plan-would-extend-free-tuition-to-rhode-island-college.

Office of Washington Governor Jay Inslee. 2019. “Inslee details plan to create a statewide free college program for Washington students.” January 11. https://www.governor.wa.gov/news-media/inslee-details-plan-create-statewide-free-college-program-washington-students.

Hardwich, Reginald. 2019. “Gov. Whitmer Touts Tuition-Free College Plan.” WKAR. February 12. http://www.wkar.org/post/gov-whitmer-touts-tuition-free-college-plan#stream/0.

[44] State Council of Higher Education for Virginia. “New Economy Workforce Credential Grant.” http://www.schev.edu/index/institutional/grants/workforce-credential-grant.

[45] Elevate Virginia. 2018. “2018-2019 Virginia Demand Occupations List.” http://www.elevatevirginia.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/2018-2019-Virginia-Demand-Occupations-List-FINAL.pdf.

[46] Bailey, John. 2018. “Income Share Agreements Are an Innovative Way of Financing Tuition — and an Investment in the Workplace of Tomorrow.” The 74. October 29. https://www.the74million.org/article/bailey-income-share-agreements-are-an-innovative-way-of-financing-tuition-and-an-investment-in-the-workplace-of-tomorrow/.

[47] Reed, Debbie, Albert Yung-Hsu Liu, Rebecca Kleinman, Annalisa Mastri, Davin Reed, Samina Sattar, and Jessica Ziegler. 2012. “An Effectiveness Assessment and Cost-Benefit Analysis of Registered Apprenticeship in 10 States.” Mathematica Policy Research. July. https://wdr.doleta.gov/research/FullText_Documents/ETAOP_2012_10.pdf.

[48] The White House. 2015. “President Obama’s Upskill Initiative.” April. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/docs/150423_upskill_report_final_3.pdf.

[49] Lerman, Robert. 2014. “Expanding Apprenticeship Opportunities in the United States.” The Hamilton Project, Brookings Institution. June. https://www.brookings.edu/research/expanding-apprenticeship-opportunities-in-the-united-states/.

[50] Office of Apprenticeship. “Learn about Tax Credits.” Education and Training Administration, U.S. Department of Labor. Last updated July 20, 2018. https://www.doleta.gov/oa/taxcredits.cfm.

[51] Office of Montana Governor Steve Bullock. 2017. “Governor Bullock Highlights Tax Incentive for Montana Businesses to Grow and Create Jobs.” June 1. https://governor.mt.gov/Newsroom/governor-bullock-highlights-tax-incentive-for-montana-businesses-to-grow-and-create-jobs.

[52] Harpel, Ellen. 2018. “New incentive program encourages apprenticeships.” Smart Incentives. September. https://smartincentives.org/new-incentive-program-encourages-apprenticeships/.

[53] Moore, Thad. 2017. “South Carolina’s apprenticeship initiative cracks growth milestone as new U.S. labor secretary advocates for on-the-job training.” Post and Courier. May 18. https://www.postandcourier.com/business/south-carolina-s-apprenticeship-initiative-cracks-growthmilestone-as-new/article_72157c86-3c05-11e7-9514-7bb6c3409ac9.html.

[54] World Economic Forum. 2018. “Towards a Reskilling Revolution: A Future of Jobs for All.” January. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_FOW_Reskilling_Revolution.pdf.

[55] Michaelides, Marios, Eileen Poe-Yamagata, Jacob Benus, and Dharmendra Tirumalasetti. 2012. “Impact of the Reemployment and Eligibility Assessment (REA) Initiative in Nevada.” January. https://wdr.doleta.gov/research/FullText_Documents/ETAOP_2012_08_REA_Nevada_Follow_up_Report.pdf.

[56] McConnell, Sheena, Kenneth Fortson, Dana Rotz, Peter Schochet, Paul Burkander, Linda Rosenberg, Annalisa Mastri, and Ronadl D’Amico. 2016. “Providing Public Workforce Services to Job Seekers: 15-Month Impact Findings on the WIA Adult and Dislocated Worker Programs.” Mathematica Policy Research. May. https://www.mathematica-mpr.com/our-publications-and-findings/publications/providing-public-workforce-services-to-job-seekers-15-month-impact-findings-on-the-wia-adult.

[57] National Skills Coalition. 2018. “America’s workforce: We can’t compete if we cut.” August. https://www.nationalskillscoalition.org/resources/publications/file/Americas-workforce-We-cant-compete-if-we-cut-1.pdf.

[58] Bryson, Donna. 2018. “Colorado Connects Career-Seekers With Contemporary Coaches.” U.S. News & World Report. August 27. https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/articles/2018-08-27/colorado-connects-career-seekers-with-contemporary-coaches.

Skillful. 2019. “Skillful Indiana Names William D. Turner, Jr. Executive Director; Launches Skillful Governor’s Coaching Corps with Indiana Governor Eric J. Holcomb.” Markle Foundation. January. https://www.skillful.com/press-release/indiana-governors-coaching-corps.

[59] Jobs for the Future. 2019. “Pathways to Prosperity Network.” https://www.jff.org/what-we-do/impact-stories/pathways-to-prosperity-network/.

[60] The Workforce Information Advisory Council, the National Skills Coalition, and The Institute for College Access & Success have all made similar recommendations to states.

Workforce Information Advisory Council. 2018. “Recommendations to Improve the Nation’s Workforce and Labor Market Information System.” Submitted to Secretary Acosta, U.S. Department of Labor. Draft for the January 25, 2018 WIAC Meeting. https://www.doleta.gov/wioa/wiac/docs/Second_Draft_of_the_WIAC_Final_Report.pdf.

National Skills Coalition. 2019 “Saying Yes to State Longitudinal Data Systems: Building and Maintaining Cross Agency Relationships.” January. https://www.nationalskillscoalition.org/resources/publications/file/11.1-NSC-WDQC_yestoSLDS_v6.pdf.

Dalal, Neha, Beth Stein, and Jessica Thompson. 2018. “Of Metrics and Markets: Measuring Post-College Employment Success.” The Institute for College Access & Success. December.

https://ticas.org/sites/default/files/pub_files/of_metrics_markets.pdf.

[61] Loewenstein, George, Cass R. Sunstein, and Russell Golman. 2014. “Disclosure: Psychology Changes Everything.” Annual Review of Economics 6 (August): 391-419. https://www.cmu.edu/dietrich/sds/docs/loewenstein/DisclosureChgsEverything.pdf.

[62] Texas Workforce Commission. 2016. “Report to the Sunset Advisory Commission: Study on the Collection of Occupational Data.” https://twc.texas.gov/files/news/2016-twc-study-collection-occupational-data.pdf.

[63] Administrative Wage Record Enhancement Study Group. 2014. “Enhancing Unemployment Insurance Wage Records: Potential Benefits, Barriers, and Opportunities.” Prepared for the Workforce Information Council, U.S. Department of Labor. September.

https://www.bls.gov/advisory/bloc/enhancing-unemployment-insurance-wage-records_fy.pdf.

[64] Ober, Andy. 2018. “’Game-Changer’ Skillful Program Coming to Indiana.” Inside Indiana Business. October 11. http://www.insideindianabusiness.com/story/39271748/game-changer-skillful-program-coming-to-indiana.

[65] Markle Foundation. 2018. “Colorado Governor John Hickenlooper, the Markle Foundation, and 20 States Launch the Skillful State Network; Introduce Skillful State Playbook.” February 14. https://www.markle.org/about-markle/media-release/skillful-state-network.

[66] Office of New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy. 2018. “Governor Murphy Signs Executive Order Creating Future of Work Task Force.” October 5. https://www.state.nj.us/governor/news/news/562018/approved/20181005b.shtml.

[67] State of California. 2018. “SB 1470 – Commission on the Future of Work.” 2017–2018 Regular Session. Introduced February 16, 2018. https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201720180SB1470.

Commonwealth of Massachusetts. “SD 1067 – An Act establishing the Massachusetts future of work commission.” 191st General Court. Introduced January 17, 2019. https://malegislature.gov/Bills/191/SD1067.

[68] Martz, Michael. 2018. “Northam names Megan Healy as first Cabinet-level adviser on workforce development.” Richmond Times-Dispatch. January 3. https://www.richmond.com/news/virginia/government-politics/general-assembly/northam-names-megan-healy-as-first-cabinet-level-adviser-on/article_c2beca3f-1fea-5f6f-b01c-78d5e6fe468e.html.

[69] National Governors Association. 2018. “States collaborate to deliver results for the on-demand workforce.” August 21. https://www.nga.org/news/states-collaborate-to-deliver-results-for-the-on-demand-workforce/.