What if more police officers coached youth sports? Since the killing of George Floyd set off protests and a national epiphany about police brutality and race in America, that question has lingered with me.

What if as a society we more intentionally found a way for White police officers to connect with Black and Latino youth and their families positively? What if more cops actually know the names of people who they serve and become familiar with who they are? Could barriers come down to regain some level of trust by police and communities if they see each other in a new light through sports?

“The history in our country has told us that sports have united folks for a very long time. Sports are it. Everyone loves it,” said Arshay Cooper, the central figure in the inspiring documentary “A Most Beautiful Thing.” The must-see film chronicles the first Black high school rowing team in this country as rival gangs from the West Side of Chicago came together to row in the same boat and, 20 years later, with police as well.

The former Manley High School rowers and police officers learned from each other. They trusted each other in the water. They joked with each other. They saw each other differently.

“Yes, cops can coach kids,” Cooper said. “But to be even more effective is when cops are doing things with adults first in a community. Have cops coaching with the parent or the pastor or the Black business owner. At the end of the day, all the Black kids on the West Side who came to our regatta race and shook hands with police, it’s because the Black adults did it. The Black men said, ‘This is how we come together.’”

I’m not naïve to our country’s racial divisions. By no means is this to suggest that coaching kids is the only answer to systemic racism in policing. As defined by Washington Post police reporter Radley Balko, systemic racism does not mean everyone in the system is racist, but rather the systems and institutions produce racially disparate outcomes regardless of the intentions of the people who work within them.

I’m not naïve to our country’s racial divisions. By no means is this to suggest that coaching kids is the only answer to systemic racism in policing. As defined by Washington Post police reporter Radley Balko, systemic racism does not mean everyone in the system is racist, but rather the systems and institutions produce racially disparate outcomes regardless of the intentions of the people who work within them.

Black men are about 2.5 times more likely than White men to be killed by police, according to a 2019 study published by the National Academy of Sciences. Black women and Latino men and women are also more likely to be killed by police than White people of their gender.

“When you consider that much of the criminal justice system was built, honed, and firmly established during the Jim Crow era … this is pretty intuitive,” Balko wrote, highlighting studies he believes shows there is overwhelming evidence of racial bias in our system. “The modern criminal justice system helped preserve racial order – it kept Black people in their place. For much of the early 20th century, in some parts of the country, that was its primary function. That it might retain some of those proclivities today shouldn’t be all that surprising.”

For many people of color, distrust and fear of police are real and not easily going away. Like so many Black parents, Yolanda Wood has had conversations for years with her children about what to do if stopped by a police officer in order to survive the encounter. Her husband is a corrections officer in Buffalo. Their 11-year-old son has participated in football, basketball, and swimming at the Buffalo Police Athletic League, but his mom reported over the summer that he doesn’t want to return to PAL nor ever be coached by an officer.

“He says he would be nervous and afraid and doesn’t know if he can trust them,” Wood said. “We had to have a conversation about not being afraid and there are more police for you than against you. It would be awesome for police officer training and information to be shared with the community about what they’re doing to get better. Sports are an excellent way to do it, if there are educational opportunities around it, such as biased training. You’d be surprised at how many kids think police officers are bad.”

If out-of-uniform cops are coaching kids how to improve as an athlete and a person, does that help change the child’s perception of all police? More importantly, does that help the officer reconsider implicit biases about people in the community where they work and result in different reactions while facing stressful situations on the job?

If out-of-uniform cops are coaching kids how to improve as an athlete and a person, does that help change the child’s perception of all police? More importantly, does that help the officer reconsider implicit biases about people in the community where they work and result in different reactions while facing stressful situations on the job?

These are not hypothetical questions. Some literature reviews over the past 20 years suggest that community-based policing and Police Athletic Leagues may help to prevent an individual from committing crimes or engaging in socially unacceptable behavior. There’s less empirical evidence on an equally important question: Does positive interactions with police through sports positively affect a person’s attitude toward all police, and does it positively impact police behavior?

In some communities across the country, these relationships through youth sports already exist. But the dots frequently go unconnected to scale up what could be a valuable tool to improve community relationships with police – cops as coaches.

If out-of-uniform cops are coaching kids how to improve as an athlete and a person, does that help change the child’s perception of all police?

Chicago

The Chicago Police Department is predominantly White. It’s a place where Sergeant Jermaine Harris, who is Black, didn’t find fellow officers easily interested in coaching Black youth on the West Side, where gun violence is common.

“There’s somewhat of a fear because we don’t know each other,” Harris said. “Remember when you’re a youngster and there’s a school dance with the boys on one side and girls on another? That dynamic plays out. It’s about being uncomfortable around each other. We have to intentionally create the opportunities.”

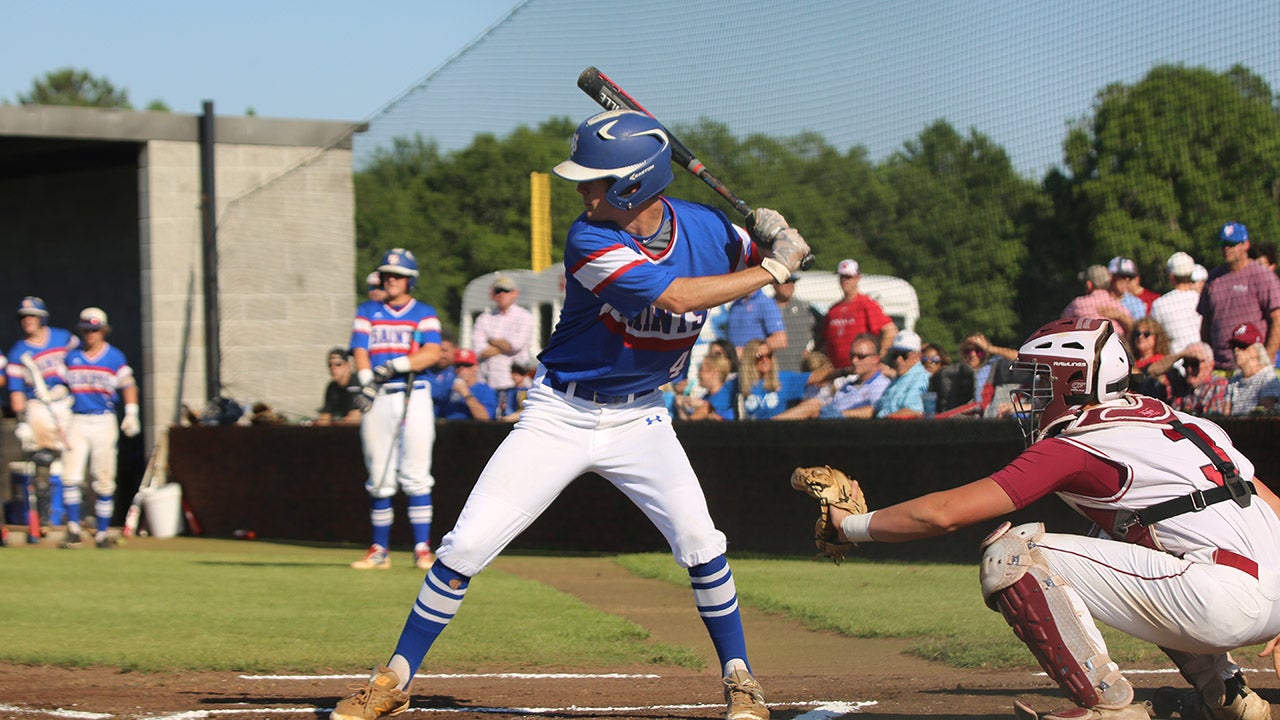

So, Harris did that. Chicago Westside Sports, which he helps organize with City of Refuge Chicago, combines local police, churches, and community nonprofit organizations. Every youth team in the league has one coach from each of those three sectors – the idea being that police, churches, and nonprofits are the neighborhood entities that can best provide resources and create collaboration. When the volunteer-based organization started in 2019, about 45 police officers served as coaches for 700 youth, ages 8-14, in baseball, basketball, and archery.

So, Harris did that. Chicago Westside Sports, which he helps organize with City of Refuge Chicago, combines local police, churches, and community nonprofit organizations. Every youth team in the league has one coach from each of those three sectors – the idea being that police, churches, and nonprofits are the neighborhood entities that can best provide resources and create collaboration. When the volunteer-based organization started in 2019, about 45 police officers served as coaches for 700 youth, ages 8-14, in baseball, basketball, and archery.

During the pandemic, the partnerships have led to remote e-learning sites staffed by mentors from faith-based organizations, nonprofits, and police departments. These mentors invest 14 hours per week into youth at three sites.

A 2019 Gallup poll found 60% of adults living in Chicago’s low-income neighborhoods said most people in their area view local police negatively. Almost six in 10 low-income residents said they know “some” or “a lot” of people who have been treated unfairly by the Chicago police.

There’s some hope that youth sports can help change some perceptions. Though it wasn’t a scientific survey (there’s no money for it), Chicago Westside Sports surveyed 100 youth baseball players and found 68% agree with the statement “I trust police officers.” Also, 66% agreed with the statement “Chicago Police Department listens to the concerns of the community.” No baseline data was collected before the organization launched.

“Now I see kids looking into a police car to see whether the officer is their coach so they can wave and say hi,” Harris said. “Other kids ask the kid, ‘How do you know him?’ It changes the dynamic when the families and parents are seeing the officers outside their jobs.

“And it’s a huge benefit for police officers, who are inundated with shootings and constant crisis. When you’re coaching a sport, you remove yourself from that world and step into the place of positivity. Now the kids you see aren’t victims of crime or criminals. They’re laughing and smiling and doing normal things kids do. It’s an easy relationship builder when you put a ball out there. That’s a thing we can all bond on.”

There are definitely challenges. Some community members have remarked to Harris that the police officers who show humanity as coaches are the exception, not the rule. Some police officers pushed back too. Harris said that personal requests of officers to join work best, instead of someone from outside the department making the ask.

The Chicago Police Department counts coaching toward officers’ work hours, usually as part of their eight-hour tours. Before the pandemic, officers spent about six hours each week in three-month stints as a coach. The officers are strongly encouraged to get trained in coaching, learning about topics such as the language to use with youth, and crisis intervention.

The Chicago Police Department counts coaching toward officers’ work hours, usually as part of their eight-hour tours. Before the pandemic, officers spent about six hours each week in three-month stints as a coach. The officers are strongly encouraged to get trained in coaching, learning about topics such as the language to use with youth, and crisis intervention.

“Once you start to recognize why young people are lashing out, that changes how we look at things,” Harris said. “Sometimes I think community policing turns into a gimmick – we all turn up and take photos once and shake some hands. Community policing is stability and consistency. Everything can’t be sit down and talk. How do we beyond that to make it action? The first stage is conversation, but it can’t be the only stage. We have to actively create programs and policies in our neighborhoods and communities. That’s where I really want to push this and take advantage of sports across the whole city.”

“Now I see kids looking into a police car to see whether the officer is their coach so they can wave and say hi. Other kids ask the kid, ‘How do you know him?’ ”

Detroit

It took a village to raise former NBA All-Star Chris Webber as a child, including police officers. “I was lucky to have great programs like PAL, where you know police officers and the ones that had game would coach us,” Webber said. “They would talk to us after (games), and it was a whole system – a whole program, a whole neighborhood, a whole community.”

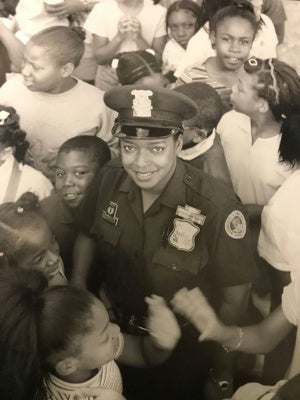

Detroit PAL was created in 1969 as a response to the violent riots that engulfed the city. In the aftermath of the 1967 uprising, a young police officer named Judith Bayer Dowling approached Police Commissioner Johannes Spreen about sponsoring a youth sports program, according to The Detroit News. A year later, their efforts merged with the National Police Athletic League, whose origins trace back to the early 1930s in New York City.

In any given year, Detroit PAL has about 200 to 300 officers who participate in mentoring, coaching, or team programming for about 10,000 youth. A 2013 survey by Detroit PAL found that 86% of youth said they had more respect for police officers after being coached by them.

In any given year, Detroit PAL has about 200 to 300 officers who participate in mentoring, coaching, or team programming for about 10,000 youth. A 2013 survey by Detroit PAL found that 86% of youth said they had more respect for police officers after being coached by them.

“These exposures as a young person help to bridge that gap between a parent, a family member, or a neighbor who’s had a negative experience and think all officers are bad,” said Detroit PAL CEO Robert Jamerson. “What PAL can do for these kids is unlearn some things from adults and really find an appreciation for these police officers. It also helps the police officers to be able to understand the importance of dialogue and communication with this generation, who may ask more questions.”

A challenge for Detroit PAL, and many other police athletic leagues, is funding. “We’ve suffered tremendously with COVID-19 just to be viable,” Jamerson said. “We’re only prepared to serve 3,000 to 4,000 kids in 2021 when our capacity over the years has reached 15,000. If people are looking to help health disparities, close inequity gaps, and build community relationships, don’t forget about police athletic leagues.”

“It’s an easy relationship builder when you put a ball out there. That’s a thing we can all bond on.”

Minneapolis

The city where George Floyd was killed by police faces fierce public debate over whether to “defund the police,” and what that even means. Months after failed efforts to dismantle the Police Department, the Minneapolis City Council voted in December to divert nearly $8 million from the proposed $179 million policing budget to other city services. The money will help the city’s Office of Violence Prevention, support mental health professionals who can respond to incidents without police, and help city workers outside the Police Department process minor complaints, according to The New York Times.

“I asked a Black Lives Matter sister to explain ‘defund the police’ and I respect her answer,” said Commander Charlie Adams, a high school football coach who leads the Minneapolis Police Department violent crimes division. “They’re not saying get rid of cops. They’re saying invest some of that money in the community. I agree. But when you cut the department by several million dollars, you lose community engagement, you lose the Police Athletic League, you lose those things people respect. So, who does that affect? Those Black families.”

Charlie, who is Black, selects the cops who work with Minneapolis PAL. Unfortunately, he finds that the officers who need to build community relationships as coaches aren’t interested in volunteering.

Charlie, who is Black, selects the cops who work with Minneapolis PAL. Unfortunately, he finds that the officers who need to build community relationships as coaches aren’t interested in volunteering.

“We hire these officers and they all want to come and serve and be a good police officer,” Charlie said. “Once they get on the streets, the reality seeps in and they’re dealing with all the bad stuff society doesn’t want to deal with, and they become cynical and think all they have to do is ride the squad car and answer calls. So how do we get other officers who have been there 18 years to understand, ‘Hey, this is what’s going to keep you sane and keep you happy doing this job?’ When you coach and see a person do well from that, that makes you feel good.”

Charlie’s son, Charles, is a popular football coach at Minneapolis North High School who was raised on Minneapolis’ North Side. He could have left his neighborhood behind but never did. He is widely praised for knowing how to defuse tough situations.

Basically, the entire Minneapolis North coaching staff is cops. They show up to practice in their police uniform because trust has been built over time, but it’s not easy. Players have said that most police officers make them feel uneasy.

“Our team knows why we’re here and we’re trying to make them better,” Charles said. “Then on the other side you have players on our team, Black and Brown, who see the systemic racism and how things are, and they’re torn. They’re like, ‘I have a good experience with this group of people, but on the other side I see bad things.’”

In 2016, Charles became the first Black head football coach in Minnesota to win a state championship. He can’t identify another head football coach in the state who is a police officer and wishes there were more. He found that coaching and serving as a school resource officer made him a better cop.

In 2016, Charles became the first Black head football coach in Minnesota to win a state championship. He can’t identify another head football coach in the state who is a police officer and wishes there were more. He found that coaching and serving as a school resource officer made him a better cop.

“It took me from leaving being a street cop to having a better perspective on how to deal with situations, especially juveniles,” he said. “I’m better at communication and patience – a lot of patience. My patience is way different from 10 years ago. I became more of a mentor and not about enforcing the law.”

In June, the city’s school board voted to end its contract with the Minneapolis Police Department, meaning Charles remains as a football coach but no longer works inside the school as an officer. He returned to being a beat cop before leaving the police force in the fall to lead security for the Minnesota Twins while still coaching. “A difficult decision,” Charles told The New York Times. “But police work no longer felt the same.”

“How do we get other officers who have been there 18 years to understand, ‘Hey, this is what’s going to keep you sane and keep you happy doing this job?’ ”

‘Youth sports break so many barriers’

The video of Floyd’s death “will set policing back 10 or 20 years in terms of trust,” Charles said. “Maybe more.” Police serving as youth sports coaches is not a cure for America’s problems with race and policing. Much more is needed.

Arshay Cooper, who united former Chicago gang members with police to train and row in a regatta, hears some activists say those types of connections are fake. But Cooper remembers how they all interacted, even when it was uncomfortable at first and his friends – some of whom served jail time – wanted no part of hanging out with the police.

Cooper learned that the Chicago Police Department officers have a high suicide rate – it’s 60% higher than the national average for law enforcement officers, according to the U.S. Department of Justice – because they see the same things the community sees. He learned police feel similar pain and share similar fears.

“Marching for change is not good enough. I can’t just have a bullhorn,” Cooper said. “I don’t want to see my daughter many years from now standing on the opposite side of cops holding the sticks. We need to have uncomfortable conservations, and sports create those conversations and you can do them in a way that’s smart. When they’re done right, youth sports break so many barriers.”

So, starting in 2021, let’s get it right—and include police in the equation.

Fund initiatives that can recruit more cops as coaches. Get them trained in the key competencies to work with youth, including training in social and emotional development. Use team activities for police to get to know their athletes’ parents and engage with the community.

This will be hard. Cops as coaches requires uncomfortable—and sometimes upsetting—conversations and interactions that are easier to avoid in our individual lives. Help can come from government, industry, foundations, police chiefs, unions, and community leaders creating opportunities and incentives for this to happen.

If we can recognize the power of sports to address shared goals around one of the toughest challenges in society, that would be a most beautiful thing.