A Short Guide to the Longevity Economy

This year’s Aspen Ideas: Economy gathered 500-plus leaders and innovators in Newark, New Jersey, for a two-day event that anchored the story of our global economy in real people, real places, and real dialogue, creating a deeper understanding of the forces of change in our economy and our lives. As the program came together, a few throughlines emerged, leading us to organize sessions that highlighted three themes: the Creative Economy, the Ownership Economy, and the Longevity Economy.

“It’s truly a profound economic shift that the world is going to witness in the next two decades,” said Anu Madgavkar of the McKinsey Global Institute, on stage at Aspen Ideas: Economy in Newark six weeks ago. “We’re all already in the middle of it. This is not something that we have to wait for to unfold.”

Five years ago, about 1 billion of earth’s humans were older than 60; by 2050, that number is predicted to more than double, thanks to advances in healthcare, nutrition, and global standards of living. But simultaneously (and perhaps for many of the same reasons), birthrates have been falling. “Currently, we have about four people available to support every retiree over the age of 65,” noted Madgavkar. “That’s going to shrink to two people in the coming two decades.”

That math has many economic thinkers, both macro- and micro-, referring to this trend as the “longevity crisis,” but it’s just one aspect of the growing “longevity economy.”

The long tail of longevity

The longevity economy is a multi-faceted, multi-sector beast, with impacts on health, savings, investment, caregiving, employment, housing, and mobility. By 2030, the market size of the over-60 set is expected to reach $8 trillion. All that spending power creates a “senior gap,” in which people’s consumption continues while their labor income falls. After this giant demographic shift, that gap will feel like imposing an additional tax burden of 10 percentage points on the labor income of the economy overall. Globally, a report by the World Economic Forum finds that “if ageing-related fiscal policies do not change, the typical government would run a deficit of 9.1% of gross domestic product (GDP) by 2060, compared with 2.4% in 2025.”

On an individual basis, the cost of living longer is no less dire. Another WEF report predicts that on that 2060 timeline, people worldwide could risk outliving their retirement savings by between eight and twenty years.

Can savings save us?

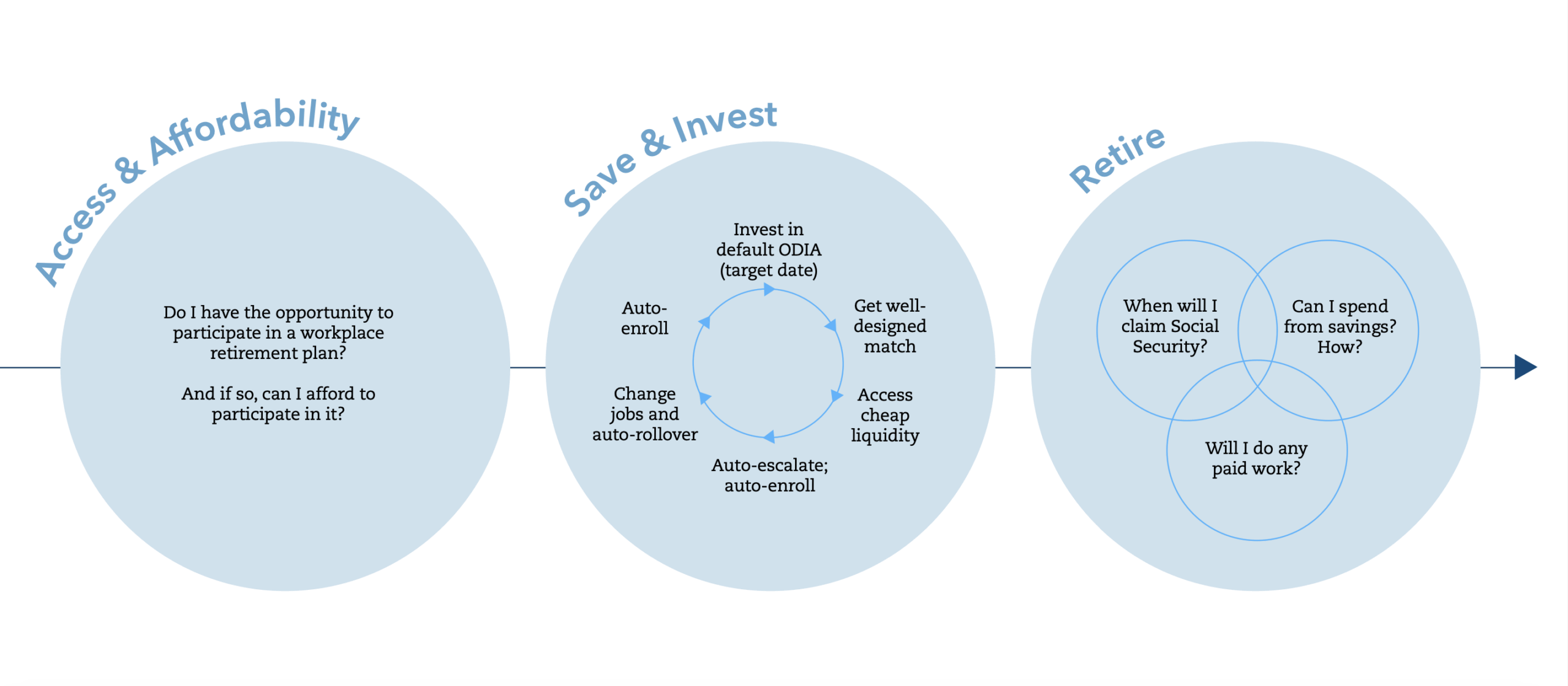

These trends didn’t exactly sneak up on us. For nine years, the Aspen Institute Financial Security Program has convened the Aspen Leadership Forum on Retirement Savings, gathering leaders from industry, government, consumer advocacy, and academia to address the coming challenges to America’s retirement savings system—and a host of current ones. This year’s report from the convening, What’s the Future of Retirement Savings? We Get to Choose, lays out the facts, built around the Retirement Savings Lifecycle: Access, Save and Invest, Retire.

Since the introduction of the first 401(k) in the 1980s, workplace-based retirement accounts have amassed nearly $30 trillion in wealth held by 71 million households, covering 54 percent of Americans. But some 56 million American workers still lack access to workplace retirement plans, and another 23 million who do have access aren’t participating (and 59 percent of those incorrectly believe they are currently saving for retirement). Furthermore, private markets have become the primary engine of wealth creation but remain largely inaccessible to workplace retirement savers, creating a two-tiered investment landscape.

Costs of childcare, housing, and medical care have grown faster than inflation, which can delay the start of savings. In many communities, people may prioritize helping family and friends in need before putting money away for themselves. Low wage growth and the rise of gig work have made saving for retirement more difficult, and as more people change jobs more frequently, they may be tempted to cash out savings rather than go through the hassle of switching them to a new system.

New thinking about growing older

While retirement savings leaders work on fixing the infrastructure of the longevity economy, other leaders are helping us rethink the cadence of our lives. We are not only living longer, after all, but are staying healthy for longer. TIME senior health correspondent Alice Park, who moderated the Aspen Ideas: Economy session, noted that education, for instance, might not need to be frontloaded into one’s twenties, but could be “something that people dip in and out of throughout their lifetimes.” We’re already changing jobs more often, and workforce needs are constantly changing, so perhaps it’s time to normalize taking breaks between employment stints for reskilling.

And as for retirement? With smaller younger generations to support economic growth, and with older people more able (and, for many, inclined) to work, we might find that the hard stop on employment is increasingly hard to justify. Already, some Japanese senior centers serve dual purposes as places for both recreation and recruitment, helping companies to find experienced workers and helping workers find purpose. Panelist Michael W. Hodin of the Global Coalition on Aging told of how German automaker BMW, faced with closing a plant, instead attracted older workers with shorter hours and floors that were easier on the knees. “When they started measuring the productivity and the value of that plant against others around the world, it skyrocketed because the knowledge, the ideas, and the experience that these older workers had,” he said.

The goals of the longevity economy are to ensure that longer lives deliver not just more time, but more security, dignity, opportunity, and joy. That means preparing for longer lives by looking at the whole person across their entire life journey, from finance, health, and work to community and belonging.

More to Explore

Three Questions That Can Predict Future Quality of Life, Joseph F. Coughlin, MIT AgeLab

Future-Proofing the Longevity Economy: Innovations and Key Trends, World Economic Forum

The age of the longevity economy, Wolfgang Fengler, Juan Caballero, and Vijeth Iyengar for Brookings

Americans are living longer, but many are making a costly mistake about old age, Aimee Picchi for CBS NewsThe Longevity Economy Outlook, AARP Global Thought Leadership