The Changing State of the Creative Economy

This year’s Aspen Ideas: Economy gathered 500-plus leaders and innovators in Newark, New Jersey, for a two-day event that anchored the story of our global economy in real people, real places, and real dialogue, creating a deeper understanding of the forces of change in our economy and our lives. As the program came together, a few throughlines emerged, leading us to organize sessions that highlighted three themes: The Creative Economy, The Ownership Economy, and the Longevity Economy. We’ll report on each of those themes in turn.

Artistic creation is often treasured but not always valued, so the economics of creativity can be particularly hard to frame—especially as new technologies change the ways we make and distribute creative work. Famously, there is no accounting for taste, but there are many things we can measure.

Creative Accounting

At its most basic, the creative economy is the ecosystem of artistic activity that includes the people, processes, places, and products that create what we consume as culture. It’s a really big show. The US Bureau of Economic Analysis’s most recent figures, from 2023, show the arts and culture in the US represent:

- 6.6% growth rate, twice the rate of the economy as a whole

- $1.17 trillion in economic value

- 4.2% of the GDP

- 5.4 million jobs

- $37 billion trade surplus in arts exports

The creative economy includes artists and performers, composers and writers, museums and concert halls and galleries and Fringe festivals. Those front-facing artists and venues are supported by layers and layers of workers—from lighting technicians and carpenters to watercolor instructors and pointe shoe manufacturers—in highly skilled industries with strong union cultures and histories of creating good, meaningful jobs.

The creative economy isn’t all about mass entertainment and movie sets. It can be an intensely local phenomenon, demonstrated by lively downtowns full of bustling restaurants, and in the cultural commonalities that bring people together. At Aspen Ideas: Economy in Newark last week, Newark Symphony Hall CEO Talia Young spoke about how local institutions such as Newark’s museums, libraries, and the hosting New Jersey Performing Arts Center “create a space for artists to thrive, to have an equitable place to showcase their work in an affordable city.” In Newark and other communities, local arts organizations “make the space for creatives accessible, while the media and the owners of the algorithms and the platforms make it inaccessible to them.” (More on that below.)

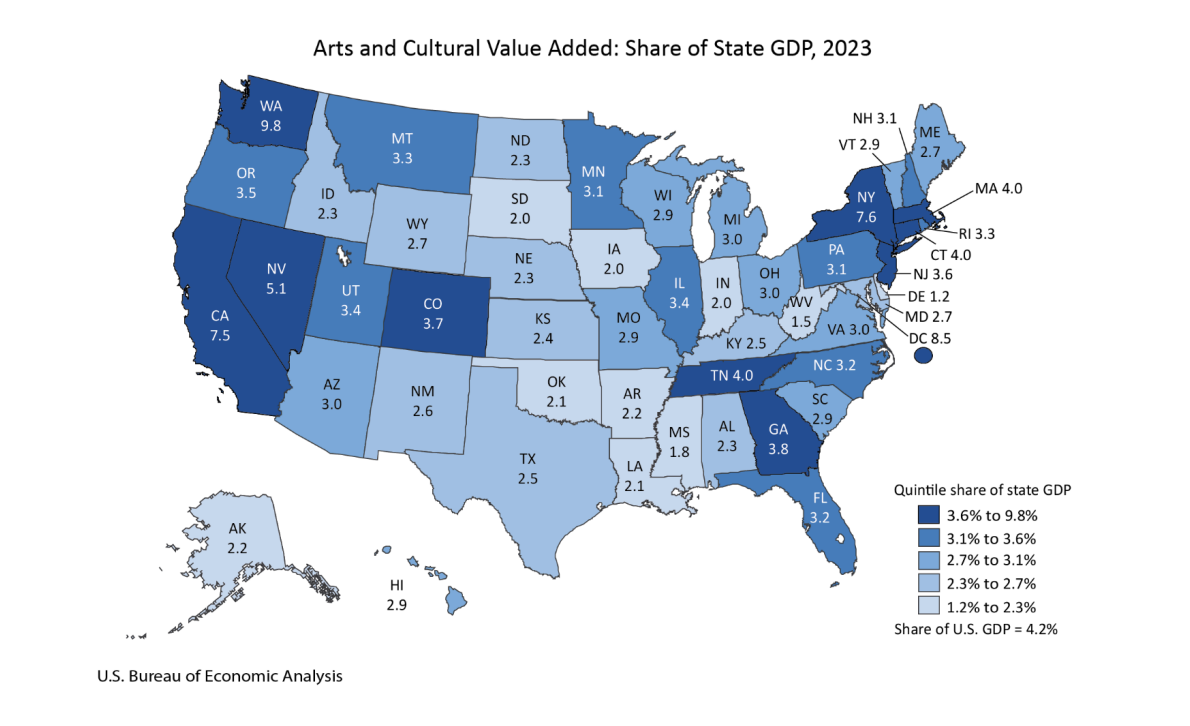

State-by-state data shows the localized nature of the creative economy. The rosy rates of growth presented here may reflect a long-awaited post-covid recovery— at the height of the pandemic, 63% of creative workers experienced unemployment—but the creative economy is now chugging along like it’s 2019.

Except, of course, that everything is different. The creative economy is facing massive cultural and technological disruption. Platforms are consolidating power, AI is redefining authorship and rights, business models are in flux, and institutions that once provided stability are eroding.

Welcome to the “Creator Economy”

“It’s like you don’t need to be in LA or New York anymore to make it, to get seen and be creative,” Shira Lazar, CEO of media brand What’s Trending. “There’s a new Hollywood that’s happening wherever you are.” She was on stage last week in Newark, as part of the panel What Happens When Everyone Is Their Own Boss? (Full video available at that link.)

“We’re seeing so many headlines, magazine covers, so much money going into the creator digital media space,” says Lazar. “It’s going to be a half-a-trillion-dollar industry by 2027. And yet for who? For a lot of companies, and of course for Mr. Beast.” New digital platforms have given creators easy access to ownership, and that’s given millions of people a way to create cultural influence—assuming they can pull enough eyeballs. That half-a-trillion by 2027 figure Lazar drops is from a Goldman Sachs report that states, “The analysts expect spending on influencer marketing and platform payouts fueled by the monetization of short-form video platforms via advertising to be the primary growth drivers of the creator economy.”

While creators do have more control over their personal brands, they rarely control the platforms they appear on—meaning promotion and payment are largely out of their hands. “How do you as an artist control your space in the market when you don’t control the space?” asks Young. There’s also potential for non-financial exploitation, she says. “When space uses you for your culture and your identity, you will continually feel robbed.”

Tomas Gonsorcik, DDB Worldwide’s global chief strategy officer, has concerns that—even as some creatives are finally finding financial footing—we’re paying the wrong people for the wrong kinds of skills. “I worry whether we are developing the right type of expertise—expertise in gaming the algo versus telling a story that moves the world forward,” he says.

And when you game the algorithm, the algorithm games you back. “I think [creators are] exhausted,” says Gonsorcik. “Once you jump on that content treadmill, the platforms incentivize new content creation all the time.”

Disrupting the disruption

Of course, none of this may matter even in the short term. Generative AI is reshaping how content is made, shared, and monetized. Generative AI is frequently derided as a “plagiarism machine,” trained on the creative labor—and intellectual property—of actual humans. Illustration, animation, and video production careers have been buried under AI slop, and workers in the physical arts-supporting ecosystem are finding themselves made algorithmically redundant. Even the stars of this new era are often glorified gig workers, rising-and-grinding in the quest for a new viral idea. (The Aspen Institute has been prompting conversations on AI and the nature of artistic work on event stages, in guidance reports, and in articles for nearly a decade.)

Not every member of the creative economy bristles at embracing new technology, however. “I really think the role of artists in this conversation is to use these tools to explore, to experiment with these things that are already so implicit in every aspect of our daily lives,” says poet and artist Sasha Stiles. At Aspen Ideas: Economy, she joined Audible CEO Bob Carrigan for a more positive take on AI tech. Watch Protecting Creativity in an AI Era.

More to explore

Guerrilla Creativity, 2024 Aspen Ideas Festival panel

The Creative Economy Is Booming. Why Aren’t Creatives?, Shain Shapiro, Forbes

K-pop blueprint: Drawing inspiration from South Korea’s creative industries, UN Trade & Development reportThe impact of GenAI on the creative industries, and the ethics and governance we must put in place, World Economic Forum