I was recently given a career achievement award – which was a little unnerving since I’ve still not decided what I want to be when I grow up – and it gave me the opportunity to reflect on the intersection of technology and journalism. Because of the disruptions caused by digital technology, journalism is completely different that it was when I became a reporter more than three decades ago. Most of the changes are good, but there are two big things that I think we need to fix.

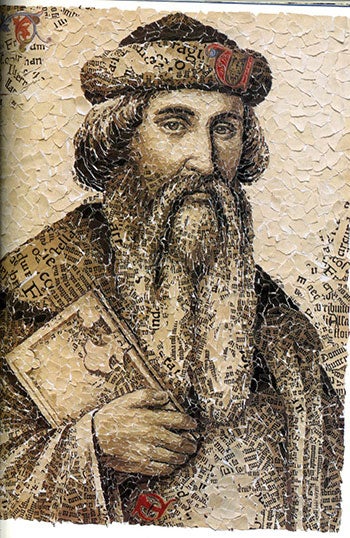

I’m writing now about Leonardo Da Vinci, who was born in 1452, the same year that Gutenberg printed his first bibles. Leonardo never went to a university and knew little Latin, but the new technology allowed him to teach himself everything from anatomy to zoology by reading books.

I’m writing now about Leonardo Da Vinci, who was born in 1452, the same year that Gutenberg printed his first bibles. Leonardo never went to a university and knew little Latin, but the new technology allowed him to teach himself everything from anatomy to zoology by reading books.

Leonardo left more than 7,000 notebook pages of drawings, thoughts and ideas. They’re all on paper, which makes them extraordinarily easy to access even after five centuries. Indeed, Leonardo’s notes are far easier to access than our e-mails, tweets, blog posts, and Facebook pages will be five centuries from now. When I was meeting with Steve Jobs and we were trying to get the emails he had sent in the 1990s, they were impossible to retrieve, even by his tech people. When I asked a university librarian recently the best way to preserve some interesting e-mails I had, she said I should print them out on paper and put them in a box.

So amid technological change, we should remember what a good technology paper is. It’s superb at the storage and distribution and retrieval of information. It’s got an incredible battery life, and it doesn’t require backwards compatible operating systems.

In fact, I’ve often pondered what would happen if for 500 years we had been getting all of our information on electronic screens and some latter-day Gutenberg came along and said, “I can take that information and I can put it on paper and I can deliver it to your porch and you can take it on the bus or to the bathtub or backyard.” We’d say, “Wow, paper is a wonderful technology. Someday it’s going to replace the Internet.”

When the Internet was devised fifty years ago, its underlying technology, known as packet switching, decentralized the control of information flows. Instead of central hubs that authorities could control, each node of the Internet had the power to originate, forward, and receive information. If censors or an enemy tried to restrict some of the nodes, the network would just route around them.

When I was at Time magazine in the 1990s, we reported that the Pentagon had funded this design so it could withstand a Russian attack. One of the graduate students who helped devise the network wrote a letter saying that was untrue. After all, he pointed out, one reason they were graduate students in the 1960s was to avoid the draft; they weren’t trying to help the Pentagon. Time didn’t print the letter, because the person who headed the Pentagon office said that it was indeed designed to survive an enemy attack, but of course they hadn’t told the graduate students that. He later said to tell the former graduate students that he was on top and they were on the bottom, so they didn’t know what was happening. When I told him this, one of the graduate students responded that the Pentagon official was on the top and they were on the bottom, so it was the Pentagon that didn’t know what was happening. That describes the Internet well: it’s built and controlled from the bottom up, not top down.

Networks transform everything they touch. Because of the Internet’s architecture, gatekeepers get disintermediated.

I saw how that affected world politics when I was at Time. I was in Bratislava covering the fall of communism in 1989, and I was in the hotel where they put foreigners, which meant it was one of the few places there that had satellite television. A person who worked in the hotel said, “the students like to come in here and watch the music channel.” I said they could use my room, and I came back early one afternoon so that I could meet some of them. But when I got there, they weren’t watching MTV. They were watching CNN and what was happening in the Gdansk shipyards with the revolt against the Polish communist leaders. It became clear to me that the lack of control of information was always going to lead to the demise of authoritarian regimes.

I saw this again a few years later being in a town called Kashgar in the western part of China. I went to a coffee shop, and there were three kids on a computer. I asked what they were doing and they said they were on the Internet. I asked if I could try something, and I typed in TIME.com and it was blocked. And I typed in CNN.com, it was blocked. At which point one of them elbowed me aside and… boom, Time came up and CNN came up. I said, “What did you do?” “Well, we know how to go through proxy servers in Hong Kong that the censors are clueless about.” Again I could see how this lack of ability to control information was going to change our politics.

The good thing, especially with the advent of the web, was that anybody anywhere got to publish anything they wanted and had access to any information anybody else published.

But for all of its wonders, I think that the birth of the Internet was accompanied by two original sins. First, we allowed and even indulged anonymity. I know that anonymity protects people’s privacy and allows them to say what they want. But the Internet could have been built differently, and at some point maybe it will be, so that users would have a choice. You should be able to go to the part of the Internet that’s anonymous. But you should also have the option to go to a secure layer of the network that has verified identity and authentication. That would allow you to engage in discussions and read the comments of people who are willing to take responsibility for what they say. It would make for more civil discussions. It would also permit more secure banking, easy financial transactions, fewer cyberattacks, less spam and phishing, and reduce the number of times you get emails from friends saying they’ve lost their wallet in Malaysia so could you please wire them some money via a bank in Nigeria. In the real world we spend most of our time in places where we know who we are talking to and dealing with; we should have that same option on the Internet.

There’s a tale that Plato tells in The Republic involving the Ring of Gyges. If you put on the ring, nobody knows what you’ve done, nobody knows what you said, nobody knows it was you who did something. He and Socrates discuss whether you could have a civil system and morality if people could put on the Ring of Gyges. Today’s Internet shows us that the answer is no.

I was talking to Madeline Conway, who’s been the managing editor of the Harvard Crimson. She said she spends her days trying to keep anonymous quotes out of news stories, then spends the evening reading the anonymous postings in the comments section, which are frightening.

Internet anonymity is one of many reasons that civility has been drained from our public dialogue. In fact, we have a leading presidential contender who seems like the embodiment of an online comments section.

We have lost the notion of community that was existent in the early days of the Internet with services like the WELL, started by Stewart Brand. When you logged on to the WELL, the first thing you saw was, “you own your own words.” In another words, you had to take responsibility for what you said, even if you were using a pseudonym (which you knew could be traced to your true identity). The result was that a trusted community was formed there, and it had wonderful discussions.

News on the go: Photo used under Creative Commons from Flickr user Alisa Cooper

The other original sin of the Internet was that most journalistic organizations made their content free when they put it online, and they thought they could survive on advertising revenue alone. I was in charge of new media at Time Inc., and when we first put our content on websites we thought we would charge users, either through subscriptions or a pay-per-article model. But as soon as we went online, you could look out the window of the TIME-LIFE building and see people from Madison Avenue running toward us with bags of cash to buy banner ads. Ad revenue was so addictive that we began to focus only on aggregating eyeballs for advertisers, and we gave up trying to get revenue from consumers.

That was an unsustainable business model. The amount of advertising dollars increases each year in a small way, but the number of websites grows exponentially. So, the CPMs — the all-powerful metric of online ads — from ad sales declines inexorably.

But it was worse than just an economic problem. It meant that we were no longer directly beholden to our readers.

Henry Luce, a co-founder of Time in 1923, said that a business model for journalism that was solely reliant on advertising revenue was not only morally abhorrent but also economically self-defeating. As a Presbyterian missionary’s son, I don’t know which of those two things he thought was worse.

So, I think we now have to look at the difficult task of putting these two genies back in a bottle. I think we need to offer communities that are less anonymous and more curated. Obviously there should be places that indulge anonymity, and if people want to go there, fine. But we should also create places where people can be part of communities that aren’t susceptible to trolling and anonymity – places where people take responsibility for their own words.

I think journalism is healthy these days, indeed it is vibrant. I see that every morning when I can hop around from Vox and the Atlantic and Politico to the New Orleans Advocate and the Huffington Post as well as all sorts of blogs and Twitter feeds I now rely upon.

Journalism isn’t broken. What’s broken is the business model for journalism.

So, I think we need to find ways to get revenue from users that are simpler and easier than the subscription models some newspapers have begun to make work. That’s a good line of revenue, but it’s not easy for everybody to do that.

There are times when I want an article from some obscure magazine or newspaper, but I don’t want to subscribe. I’m certainly willing to pay a dime or even a dollar for that article or that issue. It’s not the cost but the mental transaction cost that gets in the way. We need to have easy small payment systems. We need simple transactions, without passwords or PayPal rigmarole, perhaps based on bitcoins or some other digital coin wallets embedded in our browsers.

For 500 years, technology has increased the spread of ideas and the empowerment of individuals. This has bent the arc of history towards freedom, individual empowerment, and democracy. I’m convinced that this will also be true for the next 500 years. But it’ll be up to those in journalism today to rectify some of the mistakes made by people in my generation.

Walter Isaacson, the CEO of the Aspen Institute, is the author of The Innovators and biographies of Steve Jobs, Albert Einstein, Benjamin Franklin, and Henry Kissinger. He was the editor of Time and the CEO of CNN. This piece is adapted from a talk he gave at the Shorenstein Center’s Goldsmith awards at the Harvard Kennedy School.