In media appearances throughout the past two weeks, Virginia Senator Tim Kaine (D), who sits on the Armed Services Committee, has been hammering away on an idea that would sound quaint in today’s political world if the subject matter weren’t so serious. Before the nation begins implementing some kind of strategy in Syria and Iraq against the militant group known as Islamic State, Kaine wants President Obama to come to Congress for a thoughtful debate and vote on authorizing the mission. Kaine’s big idea is the Constitution’s clause giving the people’s elected representatives alone the authority to make war. But put more bluntly, Kaine wants Congress to do its job.

In an interview with National Public Radio’s Melissa Block aired before Congress returned from Labor Day recess, Kaine made the case:

Block: There doesn’t seem to have been an appetite among your colleagues, though, for a debate or a vote on this as we head into midterm elections. A number of your fellow Democrats say why put members of Congress in the position of voting on a measure that would be unpopular among their base – could hurt them on election day?

Kaine: Well, the reason we should do it, Melissa, is because we volunteered for the job, and this is the most sacred part of the job, and it is a responsibility that I will never, never cede to the president. The framers of the Constitution indicated that war should only be declared by Congress. If we’re going to ask American servicemen and women to risk their lives, we shouldn’t do it unless there is a political consensus that the mission is worthwhile.

Of course, Kaine’s right. The words are right there in Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution. “The Congress shall have the power to…declare war.” But the bigger question isn’t where the authority rests. The challenge is whether the paralyzing gridlock in Washington and the danger of repercussions for actually doing something is too great for policymakers to undertake a debate and vote.

Mickey Edwards thinks they can. Edwards served in Congress as a Republican representative from Oklahoma for 15 years. He was in the Republican leadership and served as a floor manager for parts of the debate Congress had before authorizing the first Gulf war, in 1991. Today, Edwards is a vice president at the Aspen Institute where he leads the Rodel Fellowship in public leadership, working with elected officials around the country.

First and foremost, Edwards agrees with Kaine that the debate is necessary, and required by the Constitution. “Congress has an absolute responsibility. The president doesn’t have the authority to do this without the Congress approving,” Edwards said yesterday. “There’s a serious constitutional problem, in my mind, if the president does this without authorization from Congress.”

Edwards can understand why some observers question whether the people’s elected representatives can, in Kaine’s words “bring the American public into the equation” with “deliberation and discussion in Congress.” Their track record hasn’t been great.

“I think they’re able to do this – and even more willing to do this than you think they are,” Edwards explained. “It depends on leadership. It depends, in the Senate, on [Majority Leader Harry] Reid not setting it up so there’s a predetermined outcome, and in the House on [Speaker John] Boehner doing the same thing.”

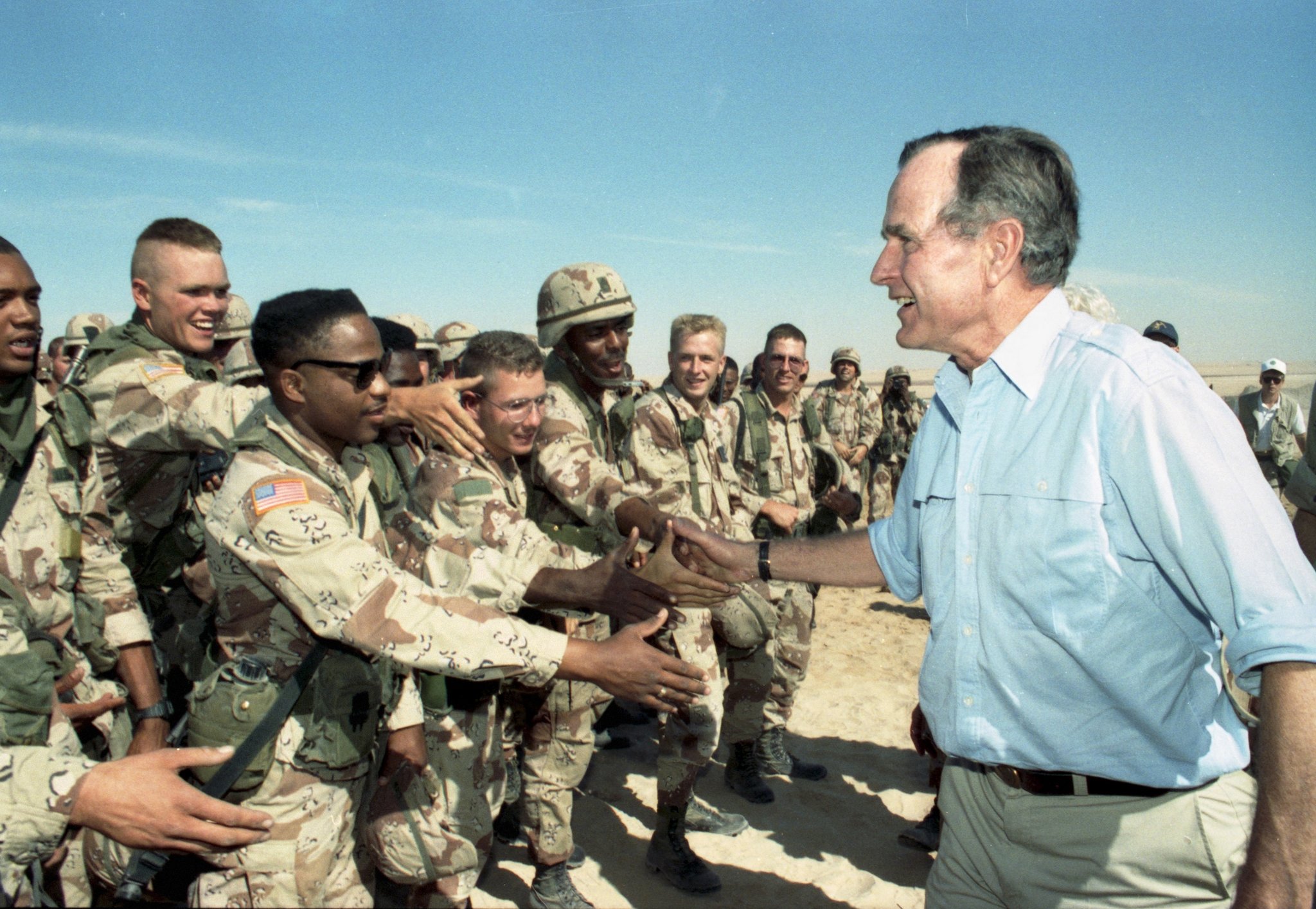

Edwards recalls his time on the House floor helping manage the debate over that first Persian Gulf military intervention in the fall of 1990. Congress then was similarly wallowing in record low approval ratings (though somewhat better than their numbers today), and there was understandable skepticism in the public eye about the U.S. responsibility to protect an oil-rich emirate most people couldn’t find on a map.

“When we went into the ’91 Gulf War, I was one of the floor leaders to get Congressional authorization. That was one of the most stirring debates I’ve ever heard. Faced with this task, we had to have a serious conversation about going to war. Congress really rose to the occasion,” Edwards said. “That was really one of the great debates in American history. I actually have confidence that this Congress today could do the same thing.”

The verdict is still out. Officially, the White House hasn’t yet taken up Kaine on his offer for a sincere debate on a plan of attack against Islamic State. While the president said he would “welcome congressional support” for his strategy of coalition airstrikes and training moderates to oppose IS, he has stopped far short of tying his efforts to action in Congress. With some party leaders hinting that Congress may adjourn as soon as the end of this week, it seems unlikely Kaine will get his wish for a full and open debate on our future actions in Syria and Iraq.

“Unfortunately, too many members of Congress prefer not to make the hard choices that would be required in deciding whether to authorize military action against ISIS; it’s easier to simply let the president make the decision and take the heat,” Edwards said. “Unfortunately, the Constitution makes it clear that war and peace decisions are the Congress’s responsibility.”